Reading aloud is one of the greatest gifts we can give to children. It builds early literacy skills, introduces rich vocabulary, and develops a child’s creativity, imagination and empathy. Parents, teachers, and caregivers model reading as a form of enjoyment and entertainment and as the bond between child and adult develops, the child associates reading with pleasure. Jim Trelease, author of The Read Aloud Handbook, describes reading aloud as fun, simple, and cheap (Trelease, 2013). So, invite a child, pick up a book and unwrap the gift of literature.

Main Content

The importance of early reading cannot be underestimated. A child’s brain is most flexible early in life, especially from birth to age five. During those years of rapid growth, parents, teachers, and care givers play a critical role in a child’s development. (“The Science of Early Childhood Development,” 2007) Sharing a book with a child, creates a bond between the child and the reader while also building foundational literacy skills.

Reading aloud to a child, even as young as six-weeks old, provides opportunities to develop the child’s oral language skills, vocabulary knowledge, awareness of print and appreciation for the pleasures of reading. (“Starting Out Right,” 1999) In the early years of a child’s life, reading aloud provides opportunities for the child to hear and imitate the sounds of language which is critical to early reading success. (“Phonological and Phonemic Awareness,” 2020) Books rich with alliteration, rhyme, and predictable patterns present the listener with an opportunity to listen to and play with the sounds of language.

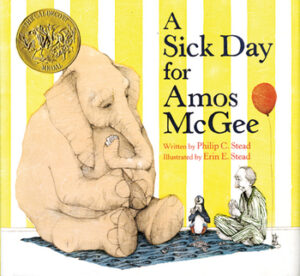

Books offer vocabulary to children that is beyond what they hear in day to day interactions. “Children listening to a picture book are roughly three times more likely to experience a new word type that is not among the most frequent words in the child’s language.” (Massaro, 2017, p. 64) For example, in the Caldecott winning picture book A Sick Day for Amos McGee by Phillip Stead, the rich vocabulary includes the words amble, limbered, and perched. These infrequent or rare words found in print extend a child’s vocabulary and provide a foundation for them to express themselves and later understand complex written ideas. Books with rich vocabulary provide the source of words for instruction. Multiple exposures to hear and use the words along with an adult who provides a child-friendly definition, leads to vocabulary acquisition. (Daly, Newgebauer, Chafouleas, & Skinner, 2015)

Books offer vocabulary to children that is beyond what they hear in day to day interactions. “Children listening to a picture book are roughly three times more likely to experience a new word type that is not among the most frequent words in the child’s language.” (Massaro, 2017, p. 64) For example, in the Caldecott winning picture book A Sick Day for Amos McGee by Phillip Stead, the rich vocabulary includes the words amble, limbered, and perched. These infrequent or rare words found in print extend a child’s vocabulary and provide a foundation for them to express themselves and later understand complex written ideas. Books with rich vocabulary provide the source of words for instruction. Multiple exposures to hear and use the words along with an adult who provides a child-friendly definition, leads to vocabulary acquisition. (Daly, Newgebauer, Chafouleas, & Skinner, 2015)

Reading aloud to young children also helps to develop their print and book awareness, or their understanding of print, its functions, and the features of a book. As adults share books with children and model how to hold the book and that there are words on the page moving from left-to-right, they are developing print awareness skills. These skills lead to the important development of concept of a word or the understanding that spoken words correspond with words on the page separated by spaces and those words convey meaning. (“Print Awareness,” 2020)

Educational benefits of reading aloud also include helping children to develop story grammar, or the elements of a book or story. With exposure to books of different genres and formats, children become more familiar with story structure and how to gain information from books. In addition, as students become more familiar with story elements, they are able to use that knowledge as they develop as writers. As students enter formal schooling, teachers use read alouds as mentor texts to model elements of writing. (Spandel, 2012) For example, a teacher may use I Wanna Iguana by Karen Kaugman Orloff to teach persuasive writing.

Clear support for the academic benefits of reading aloud or sharing literature with children have been outlined, but it is also the personal benefits to the listener that cannot be understated. Sharing stories with children builds creativity and extends their imagination. They enter new, unknown worlds outlined by authors and begin to ask the What if? Questions. A well-crafted story takes the reader to another world, and this escape from reality may be welcomed by a child who feels isolated and may also serve as relief from day to day life. (Temple, C., Martinez, M., Yokota, J., 2019, p. 236-237)

Not only can children escape their own reality, but stories can show them that they are not alone. Books provide an understanding of the universality of experience. Other children are weary of getting a haircut, the first day of school, or having a friend. Or, a child may find that other parents get divorced and other children suffer the loss of a loved one. Books could be shared as conversation starters for more difficult topics, or read to help the child put voice to their feelings. (Temple, et. al., 2019) In this way, books provide a mirror to the reader, and they see themselves in the characters in the book. Rudine Sims Bishop coined the language describing books as ways to see both yourselves and the lives of others. “Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange. These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created and recreated by the author. When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror. Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.” (Bishop, 1990, p. ix) Not only can a child relate to characters in a book, but books offer children new perspectives other than their own. In books, they can travel to other places in the world that they may never see and gain appreciation for other cultures and ways of living. Stories also let them walk in someone else’s shoes, and that experience helps to develop empathy. Just as we may teach a rare vocabulary word, we need to teach empathy, and books, especially works of fiction give us this opportunity.

Valuable and life changing benefits come from reading aloud and sharing literature with children. To develop lifelong readers and learners, we need to model the joys of reading. With a good book, you have entertainment and comfort. You can leave your own life for a time and experience a new adventure or part of the world. A reminder too that you are not alone awaits you. Pick out a good book and share it with a child and open their eyes to the magic of reading.

References

Center on the Developing Child (2007). The Science of Early Childhood Development (In Brief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

Daly, E., Neugebauer, S., Chafouleas, S., & Skinner, C. (2015) Interventions for reading problems Designing and evaluating effective strategies. In Vocabulary (2nd ed., pp.124-150). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

National Research Council 1999. Starting Out Right: A Guide to Promoting Children’s Reading Success. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/6014.

Orloff, K.K. (2004). I wanna iguana. Penguin Young Readers Group: New York.

Read and discuss stories. (2020, June 17). Retrieved February 25, 2021, from https://thebasics.org/brain- boosts/read-and-discuss-stories/

Reading Rockets (2020). Phonological and Phonemic Awareness. Retrieved from https://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading-basics/phonemic.

Reading Rockets (2020). Print Awareness. Retrieved from https://www.readingrockets.org/teaching/reading-basics/printawareness.

Sims Bishop, R. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 1(3), ix–xi.

Spandel, V. (2012). Creating Young Writers using the six traits to enrich writing process in primary classrooms. (3rd Ed.), Boston: Pearson.

Stead, P. C. (2010). A sick day for Amos McGee. New York: Roaring Brook Press.

Temple, C., Martinez, M., Yokota, J., (2019). Children’s books in children’s hands (6th Ed.) New York: Pearson.

Trelease, Jim (2013). The Read-aloud Handbook. (7th Ed.), New York: Penguin Books.