Chapter 2: History of Children’s Literature

Introduction

This chapter was written by Jenifer Jasinski Schneider in 2016, the author of an OER entitled, The inside, outside, and upside downs of children’s literature: From poets and pop-ups to princesses and porridge. The authors of A Guide to Children’s Literature received permission to use original content from this OER under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License.

At its best, children’s literature includes books of the highest caliber, representing complex plots or concepts in both word and art. Children’s literature is often defined as a collection of books written for children, read by children, and/or written about children. But this definition may be too simplistic for a not-so-simple genre.

Main Content

What is Children’s Literature?

I revise the previously provided definition of children’s literature from a collection of books written for children, read by children, and/or written about children to:

Children’s literature is an assortment of books (and not books) written for children (and adults), read by children (and adults), and written about children (but not necessarily).

That was a better definition. But it is not completely inclusive. As further evidence, I submit the following:

Children’s literature is a collection of books as old as the printing press (Figure 2.1)

Children’s literature portrays all aspects of humanity (Figure 2.3),

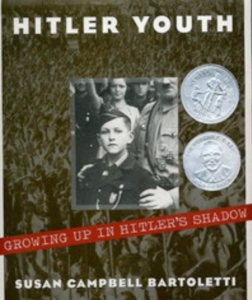

inhumanity (Figure 2.4)

and non-humanity (Figure 2.5),

all periods of human history (Figure 2.6)

and all places of this world (Figure 2.7)

as well as worlds beyond (Figure 2.8).

Children’s literature is poetry (Figure 2.9),

fiction (Figure 2.10),

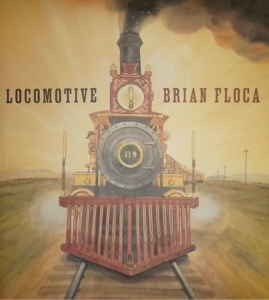

nonfiction (Figure 2.11),

argument (Figure 2.12),

and biography (Figure 2.13).

Children’s literature includes picturebooks (Figure 2.14)

and pop-up books (Figure 2.15; Video 2.1),

paper books (Figure 2.16)

plays (Figure 2.17)

and digital texts (Figure 2.18).

Children’s literature includes many stories (Figure 2.19)

and single stories (Figure 2.20),

happy stories (Figure 2.21),

sad stories (Figure 2.22),

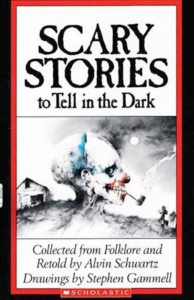

scary stories (Figure 2.23),

mad stories (Figure 2.24),

and not stories (Figure 2.25)

Children’s literature is created for and read by children, adolescents, and adults. Children’s literature is high art, extraordinary writing, and everything in-between.

It’s difficult to appreciate the 3D art of pop-up artists like Robert Sabuda and Matthew Reinhart in a 2D, non-moving, space. To see some of the intricacies in pop up books, watch this pop up video:

Video 2.1 Look, Touch, Shake, and Swipe: Pop Up Books and Interactive eBooks http://www.kaltura.com/tiny/wlrn1.

A Working Definition

Children’s literature is a label for collections of texts that are specifically written and/or illustrated for and/or about youth as well as texts that are not specifically written and/or illustrated for and/or about youth but which youth choose to read, view, and/or write. Adults are welcome to read children’s literature too—many do.

Children’s literature provides encounters with the world that shape the meaning children make of the world (Kiefer, Hepler, Hickman, Huck, 2007). Having a vicarious or “lived through” experience with literature, builds readers’ aesthetic responses and perceptions (Rosenblatt, 1978). Reading literature increases one’s sensitivity to the power of the written word (Sipe, 2008) and contributes to visual expression (Brenner, 2011; Sipe, 2011). For these reasons, adults study children’s literature as scholars, critics, educators, librarians, entrepreneurs, and social commentators.

A Brief History of Children’s and Young Adult Literature

With my almost anything goes orientation toward children’s literature broadly detailed, let’s take a look at how this body of literature came to be through selected examples and important artifacts.

The origins of children’s literature are hard to nail down. Do cave illustrations count? In my opinion, why not? There is evidence cave paintings included children (2015, November 10, Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/earth/earthnews/8798392/Childrens-prehistoric-cave- paintings-discovered.html).

I accept different formats of text as representatives of children’s literature (and by text I am referring to symbolic systems of meaning). I realize cave paintings are not “books,” but they were a form of communication most relevant and accessible to the people of that time.

I am not obsessed with the content of the cave drawings either. If hunting deer was the trending topic of ancient people, then children and young adults needed to know about it. Cave youth needed to access others’ thoughts and ideas. They needed information.

Somewhere between prehistoric cave people and the Renaissance, the Sumerians and others invented cuneiform to represent sounds that captured human speech, the Egyptians developed hieroglyphs for record-keeping, and the Chinese used oracle bones and inscriptions to communicate with their ancestors (2015, November 10, Retrieved from http://www.britishmuseum.org/ explore/themes/writing/historic_writing.aspx). Gutenberg created a printing press and the speed of information exchange increased dramatically (2015, November 10, http://www.history.com/topics/ middle-ages/videos/mankind-the-story-of-all-of-us-the-printing-press). Here are a few examples.

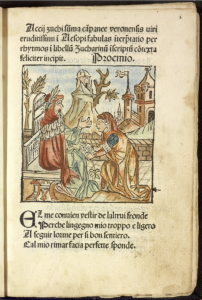

1400’s : A 1485 Italian edition of Aesopus Moralisatus by Bernardino di Benalli (Figure 2.26).

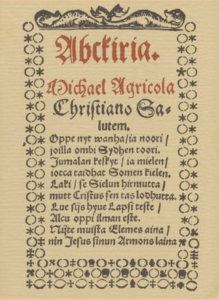

1500’s: Michael Agricola’s ABC book published in 1559 (Figure 2.27)

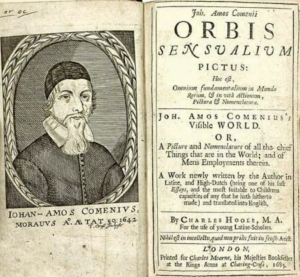

1600’s: Johannes Amos Comenius’ Orbis Pictus, 1657, is widely considered to be the first picturebook school book (Comenius, 1896) (Figure 2.28).

1700’s: The Catechism of Nature for the Use of Children by Dr. Martinet published in 1793 (Figure 2.29).

As these representative texts indicate, writing evolved across cultures and through various modes and media. Tablets, stones, pamphlets, and books were vehicles for conserving history or sharing information among scholars, the wealthy, and royalty.

Eventually, the creation of chapbooks, and other forms of cheaply-produced texts, increased people’s access to books. Chapbooks often featured rhymes, fairy tales, or alphabet books along with crime stories, songs, and prophecies; however, children were not the only target audience of these texts (2015, November 10, Retrieved from http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/ articles/n/national-art-library-chapbooks-collection/).

Fairy tales, collected by the Brothers Grimm as part of their study of linguistics, were oral stories that were shared among adults. Their work was not necessarily intended for children either (Ashliman, 2013, Retrieved from http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/grimm.html).

Of course, children read the texts of their times, or listened to the stories around them, but they only had access to the books that were placed within their lives.

Parallel to the publication of chapbooks, publishers developed instructional materials specifically for children (Video 2.2). Spelling books, primers, and alphabet books were intended to support religious and/or academic instruction for children. Yet, the notion of reading for pleasure or the production of texts specifically for children’s amusement was not a priority.

For the most part, the 18th century was the time period in which “children’s literature” became a thing. According to Professor M.O. Grenby (2015), Professor of Eighteenth- Century Studies in the School of English at Newcastle University,

“A cluster of London publishers began to produce new books designed to instruct and delight young readers. Thomas Boreman was one, who followed his Description of Three Hundred Animals (Figure 2.30) with a series of illustrated histories of London landmarks jokily (because they were actually very tiny) called the Gigantick Histories (1740-43).”

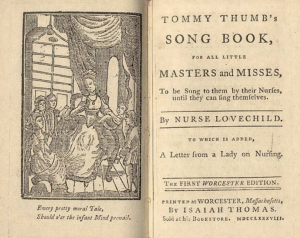

Another was Mary Cooper, whose two-volume Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (1744) is the first known nursery rhyme collection, featuring early versions of well-known classics like ‘Bah, bah, a black sheep’, ‘Hickory dickory dock’, ‘London Bridge is falling down’ and ‘Sing a song of sixpence’ (Figure 2.31).

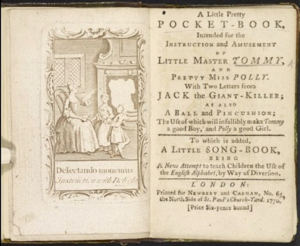

But the most celebrated of these pioneers is John Newbery, whose first book for the entertainment of children was A Little Pretty Pocket-Book Intended for the Instruction and Amusement of Little Master Tommy and Pretty Miss Polly (c.1744) (Figure 2.32). – See and read more at: (Grenby, 2015, Retrieved from http://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/the-origins-of-childrens-literature#sthash.6MIH4VoM.dpuf).

With the development of improved printing processes and the recognized value of books and literacy, the field of children’s literature shifted and expanded.

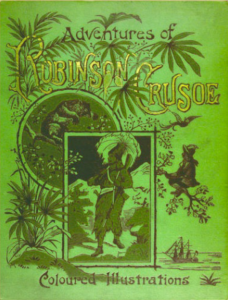

1800’s: The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe written by Daniel Defoe and illustrated by Paul Adolphe Kauffman (1884) is still widely read and this version boasts “coloured illustrations” on the book cover (Figure 2. 33).

1900’s: By the 1900’s, children’s literature was more pervasive in homes, libraries, and schools. The global importance of children’s literature is represented in books published in many languages all over the world (Figures 2.34, 2.35, 2.36, 2.37)

2000’s: More recently, children’s literature has taken a digital turn. In addition to ebooks, attempts to reflect diverse perspectives have increased with open access publishing and grass-roots promotion through social networking. For example, the Anna Lindh Foundation promotes Arab children’s literature (http://www.arabchildrensliterature.com/about).

Children’s books are an important part of civilization. The creation of children’s literature led to changes in how children read, how children learn in school, and how children understand the world. Yet none of the changes would have been possible without access to books.