Chapter 4: Art in Picture Books

Introduction

This chapter was written by Jenifer Jasinski Schneider in 2016, the author of an OER entitled, The inside, outside, and upside downs of children’s literature: From poets and pop-ups to princesses and porridge. The authors of A Guide to Children’s Literature received permission to use original content from this OER.

Main Content

Visual Purpose and Illustrative Style: Another Vehicle for Communication

Illustrations are created for all of the same purposes described above (narration, information, description, argumentation). The difference between picture books and illustrated texts is the role of the illustrations. Many books include illustrations as cover art, as chapter introductions, or to illustrate selected ideas throughout the text. In picture books, text and images are the conduits of meaning; they work together.

To analyze illustrations, readers typically examine the elements of artistic representation such as line, value, shape, form, space, color, and texture. The reader might also consider the principles of design that integrate the elements such as balance, contrast, movement, emphasis, pattern, proportion, and unity. Several experts have explored these concepts and they offer excellent criteria for “seeing” illustrations and engaging in formal analysis (See Bang, 2000; Moebius, 1986; Nodelman, 1988; Serafini, 2010; Serafini, 2011; Sipe, 1998). Other children’s literature texts go into great detail and provide numerous examples to illustrate the elements and principles of artistic representation (e.g., Charlotte Huck’s Children’s Literature; Kiefer, 2010).

Artistic Elements: Line; value; shape; form; space; color; texture;

Principles of design: balance; contrast; movement; emphasis; pattern; proportion; unity.

J. Paul Getty Museum: http://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/building_lessons/formal_analysis.html http://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/building_lessons/formal_analysis2.html

The Kennedy Center ArtsEdge: https://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/how-to/from-theory-to-practice/formal-visual-analysis

I thought I would go in a different direction. Formal analysis works really well if I want to examine one piece of art, one photograph, one collage. But picture books and illustrated texts are constructed differently. Picture books move. Not in the sense of a motion picture, which captures segments of constructed, yet fluid, movement; but more along the lines of stop-motion animation, which freezes selected moments along a continuum of time. Even so, stop-motion carries a sense of fluidity and a more detailed documentation of movement. Picture books are more episodic. So are illustrated texts. Come to think of it, so is the writing.

Authors compose text on a blank page and we use their words to comprehend the larger message. Illustrators also create images on a blank canvas and we tend to look more myopically at their techniques. Why not give illustrators the same consideration and look at the broader communicative purposes to determine what they did artistically? Why should I only examine the illustrator’s use of color, shape, texture, or pattern?

Therefore, let’s explore visual analysis as a mode of discourse that indicates the illustrator’s intent as well as the way in which the artist communicates the message.

Narrative Illustration

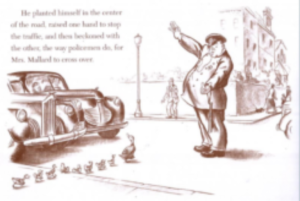

Narratives include action and events multiplied into a series. In narrative illustrations, events are depicted in a sequence of actions that advance the plot. For example, in Make Way for Ducklings, Robert McCloskey created elaborate illustrations of important incidents as they occurred in chronological order (Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

In other books, the illustrations may be more episodic through the selection of big ideas presented in small moments. In a book about the Civil War, Patricia Polacco’s portrayals of simple interactions speak volumes about the characters and their evolution as people in Pink and Say (Figure 4.3). The illustrations tell a visual story in a particular place (setting) with character development occurring within the plot.

In addition to illustrating plot sequences and character actions, illustrators also narrate by providing the right visual at the right time. In Video 4.1, I share my reading of Olivia, looking specifically at the ways in which Ian Falconer isolated key examples to illustrate the story of a little pig who is good at lots of things. Watch this video to learn how to “read” a picture book by exploring book design, by interpreting the visual illustrations, and by understanding the rhetorical moves of the printed words.

Overall, narrative illustration tells a story. Yet, just as a writer makes authorial choices with regard to sequencing, point of view, pacing, voice, and tone, the illustrator makes the same choices. The illustrator is not retelling the author’s story; the illustrator is creating his or her own visual story.

Informative Illustration

Informational books are defined as those illustrated to present, organize, and interpret documentable, factual material (ALA, nd, Sibert Medal). Informative illustrations replicate these purposes. Often the illustrations provide thick, rich details that are not always readily apparent or interpretable from the text (Figure 4.4). For example, Katharine Roy illustrates the idiosyncrasies of a shark’s circulatory system demonstrating how blood impacts body temperature (Figure 4.5). Unless a reader has an extraordinary ability to visualize the internal workings of a shark, the illustrations are essential for the reader’s comprehension of the concepts.

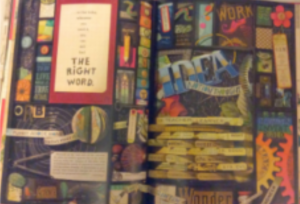

Often informative images are realistic, such as the actual photographs and documents used in The Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, & The Fall of Imperial Russia (Figure 4.6). Yet, other books are illustrated to capture a different feeling. For example, In The Right Word: Roget and his Thesaurus, Melissa Sweet chose to emphasize Roget’s work, his keeping of lists, and his aggregation of words over time (Figure 4.7), highlighting different scenes and events from his life (Figure 4.8). The spirit of Roget’s obsessive collecting and word documentation was interpreted by Sweet’s collage illustrations that have the feeling of a junk-drawer or a treasure chest (Figure 4.8).

Illustrators, just like authors, use different structures to inform readers. Some informational illustrations are organized by concept (Figure 4.9). Others dramatically recreate sequences of events (Figure 4.10). Still others use captions, comparisons, labels, titles, charts, graphs, fonts, and other text features to convey meaning (Figure 4.11).

Descriptive Illustration

Descriptive illustration is focused on the presentation of elaborative detail. The illustrations provide a visual that corresponds to or extends the details from the text. For example, in Owl Moon, Jane Yolen’s language reflects the quiet of the snow and the stillness needed to find an owl in the late night. John Schoenherr’s illustrations move beyond the main character’s thoughts to reflect her relationship with her father as well as their interactions with the expansiveness of nature (Figure 4.12).

In contrast to Owl Moon, Rosalyn Schanzer uses harsh black and white scratchboard illustrations with striking accents of red to portray the hysteria and horror of the Salem witch trials in Witches! (Figure 4.13). In Owl Moon and Witches!, the illustrations add descriptive details, elucidating themes that are not specifically mentioned in the texts.

In another example, The Boy Who Loved Math, the title informs the reader that the book is about a boy who loves math, but the illustrations show the depth of his love (Figure 4.14). Illustrator, LeUyen Pham, creates the vivid details of someone who not only loves math, but he lives, breathes, and thinks with math (Figure 4.15). This is what math obsession looks like (Figure 4.16).

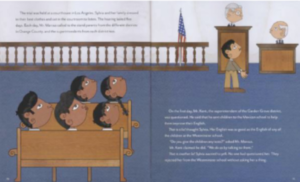

Argumentative Illustration

Argumentation through illustration is the illustrator’s ability to present issues with an evaluative perspective. For example, one of the rhetorical structures for argument is to compare and contrast. Illustrators can make this move as well. In Hey, Little Ant (Figure 4.17), Debbie Tilley uses size differences, along with character gestures and facial expressions, to help the reader understand the ant’s argument for why he should not be squashed. Argumentative illustration also presents a point of view. In Separate is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, Duncan Tonatiuh could have illustrated Sylvia’s courtroom experience from any number of perspectives (from above, close up to the main character, from the judge’s bench, from the witness stand), but he chose to place the reader behind Sylvia (Figure 4.18). As readers, when we view the page, we watch the whole scene unfold as an objective audience even though the words are written from Sylvia’s point of view.

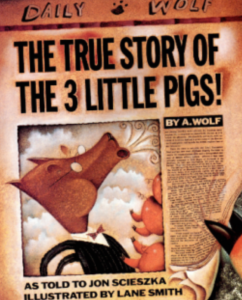

Illustrators use argumentative techniques to appeal to the reader’s ethics, reason, and emotions (Figure 4.19). In the classic picture book, The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, Jon Scieszka tells the story of a misunderstood wolf who “accidentally” causes a series of calamities in which pigs must be eaten, otherwise, their carcasses would go to waste. Beginning with the cover, Lane Smith presents the wolf’s story as journalistic truth. The wolf is a bespectacled, respectable citizen whose newspaper article is crumpled by a pig’s wicked-looking hoof. Whose side are you on?

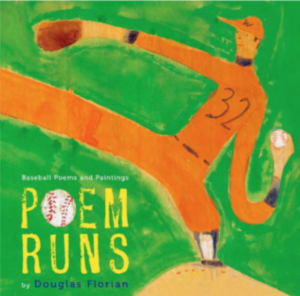

All genres, including speeches, essays, nonfiction, science fiction, and dramas use argumentation in illustration (Watch Video 4.2). Even poetic texts use argumentative illustration. For example, when you read the title of Douglas Florian’s book, Poem Runs, you may not understand the meaning or intention of the text. But take a look at the illustrations (Figure 4.20) and the author’s playfulness is apparent as he appeals to the reader’s sense of humor.

Illustrations

The quality of children’s book illustrations are so high, illustrations are shown in galleries and museums across the world.

- The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art (http://www.carlemuseum.org/) collects, preserves, presents, and celebrates picture books and picture book illustrations from around the world (Figure 4.21).

- The Mazza Museum (http://www.mazzamuseum.org/) promotes literacy and enriches the lives of all people through the art of children’s literature. Located on the campus of the University of Findlay, the museum features thousands of pieces of art from hundreds of artists.

- The de Grummond Children’s Literature Collection (http://digilib.usm.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/degrum) at the University of Southern Mississippi Collection features American and British children’s literature, historical and contemporary.

- The Kerlan Collection at the University of Minnesota (https://www.lib.umn.edu/clrc/kerlan-collection) includes original illustrations from various artists and historical illustrations as well.

- The Victoria and Albert Museum (http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/n/national-art-library-childrens-literature-collections/) in the UK holds over 100,000 books from the 16th entry to the present day.

- The Norman Rockwell Museum (http://www.nrm.org/) hosts a Distinguished Illustrator Series.

-

Figure 4.22. The Maurice Sendak Collection at the Rosenbach Museum (https://www.rosenbach.org/learn/collections/maurice-sendak-collection). Maurice Sendak’s illustrations are exhibited in the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia, PA (https://www.rosenbach.org/learn/collections/maurice-sendak-collection) (Figure 4.22). Sendak was also featured on the American Masters series on PBS (http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/maurice-sendak-about-maurice-sendak/701/).

- Seven Stories is the National Centre for Children’s Books in the UK (http://www.sevenstories.org.uk/). The collection features authors and illustrators, thousands of books, and rotating exhibits.

- Trinity College Dublin Library holds over 150,000 children’s books. The collection is accessible through the National Collection of Children’s Books (https://nccb.tcd.ie/about) and features periodic exhibits such as Upon the Wild Waves: A Journey through Myth in Children’s Books (https://www.tcd.ie/Library/about/exhibitions/wild-waves/).

In contrast to the laborious methods of illustration that were in place during the early years of children’s literature publication (Video 4.3), modern digitalization and printing processes have created countless possibilities for children’s book illustration.

There is no particular style or media that is more successful than others. Children still prefer color rather than black and white. And they tend to gravitate toward realistic, detailed illustration rather than sparse, surreal interpretive scenes. But there are many exceptions to these general preferences (Figure 4.23). Yes, grocery store books (common, lower-quality books) may have similar looks, but the children’s books that have literary value, artistic value, maintain a reader’s interest, and stand the test of time are illustrated from a broad spectrum of styles and media. Any medium can be found in children’s literature.

Acrylics (Figure 4.24)

Crayon (Figure 4.25)

Collage (Figure 4.26)

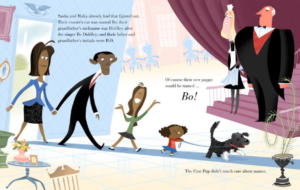

Digital (Figure 4.27)

Gouache (Figure 4.28)

Pastels (Figure 4.30)

Pen and Ink (Figure 4.31)

Scratchboard (Figure 4.32)

Watercolor (Figure 4.33)