Chapter 9: Traditional Literature

Introduction

This chapter was written by Jenifer Jasinski Schneider in 2016, the author of an OER entitled, The inside, outside, and upside downs of children’s literature: From poets and pop-ups to princesses and porridge. The authors of A Guide to Children’s Literature received permission to use original content from this OER.

“Traditional literature” is the collective name for the text types that began through oral storytelling and are now preserved in iterations of writing. With oral origins, there were no “original” versions to track down and no identifiable authors to credit. However, as time passed, many individuals decided to collect, organize, and write these stories for collection and distribution.

Main Content

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm (Figure 9.1), two German brothers who were aspiring lawyers with a hobby of collecting folktales, took positions as librarians in 1808 and became linguists, folklorists, and scholars of medieval studies (Ashliman, 2015). They traveled through Germany and spoke with families to acquire stories and document the language with which the stories were told. They published a collection of Children’s and Household Tales for wider distribution and their names became synonymous with these stories (Figure 9.2). The Brothers Grimm did not create the stories; they collected and interpreted them. Now the stories are preserved in time. The Grimms’ collections are often considered the originals, but the Grimms altered the stories across versions (Video 9.1).

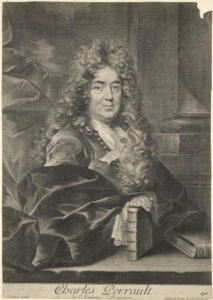

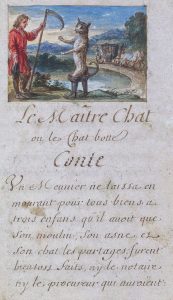

In a different country, Charles Perrault (Figure 9.3), a respected academic who lived almost 100 years before the Brothers Grimm, engaged in the preservation of stories told in France. In 1697, he published a volume of Stories or Tales from Times Past: Tales of Mother Goose (Figure 9.4) and included the stories of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Little Red Riding Hood.

In another time and place, Joseph Jacobs (Figure 9.5), an Australian, Jewish scholar, folklorist, and literary critic compiled collections of English tales and legends (Bergman, 1983). Capturing stories such as Jack and the Beanstalk and The Three Bears, Joseph Jacobs preserved English legends as well as Jewish, Celtic, and Indian folklore (Figure 9.6). http://www.archive.org/stream/morecelticfairyt00jaco#page/n7/mode/2up.

- Professor D.L. Ashliman created a website for Charles Perrault. http://www.pitt.edu/~dash/perrault.html

- Project Gutenberg has published a 1922 version of The Tales of Charles Perrault http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29021/29021-h/29021-h.htm

- Collections of Joseph Jacobs work can be found at http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/eft/

Joseph Jacobs wrote explicitly about the people who passed down these tales from generation to generation. He noted, “in dealing with Folk-lore, much was said of the Lore, almost nothing was said of the Folk” [Jacobs, 1893: 233]: http://england.prm.ox.ac.uk/englishness-Joseph-Jacobs.html

- Oral traditions occur across all cultures, countries and time periods. The European origins of the Brothers Grimm, Charles Perrault, and Joseph Jacobs reflect Anglo-Saxon preferences in publishing and its corresponding impact on U.S. literary history.

- Scholars have collected African, Russian, South American, Asian, and Native people’s stories as well. http://www.worldoftales.com/index.html

- http://www.unc.edu/~rwilkers/title.htm

- I am focusing on the traditions of Grimm, Perrault, and Jacobs because I want to make a point about the evolution of oral stories into print and across time.