7.1 Communicating Across Cultures

Communications professor John Baldwin (2015a) cites this story, emailed to him from a student participating in a study abroad experience:

I found your email to be most practical and helpful. I’ve kept in touch with my family [in the US] and like you said even in short emails I noticed I’ve become more aware of a sense of frustration with American waste, greed, materialism, consumerism. I can tell especially with my brother and sister I’m going to have a hard time telling them about my experiences and cultural differences that I’ve been exposed to. In one of the emails I sent to my brother I was telling him how it’s amazing to see the value change between the US and Ireland. In his response to this he asked me ‘Did you get to see the Superbowl?’ I haven’t spoken to my family, well at least my brother, after his question.

Encounters with other cultures can be life-changing experiences. They can also lead to frustration, as here, when our friends or family don’t understand or are unwilling to accept the changes we have undergone, such as acquiring new interests or points of view. Intercultural encounters vary in scope, context, and outcome. We may have contact with a single individual in a brief exchange, or we might live and work in a new culture for an extended period of time. We will be discussing in this unit the range of experiences, as well as potential outcomes, including personal conflicts and culture shock. We will also look at mediated intercultural encounters, through news reports, stories and the Internet.

Personal encounters

We discussed in a previous unit that meeting people we don’t know often results in uncertainty and anxiety. That uncertainty is increased when we know little about the other person and have to make assumptions. We may act or speak based on those assumptions. That may prove not to be a problem, particularly if we are open to changing our perceptions, work to accommodate the other person’s communication style, and adjust our speech and behavior accordingly. But it’s also possible that the encounter leads to miscommunication, bruised feelings, and arguments. Misunderstandings and conflict occur all the time when human beings are involved, even among people we know well or are related to. The opportunity for conflict is all the more plentiful when different languages and cultures are involved.

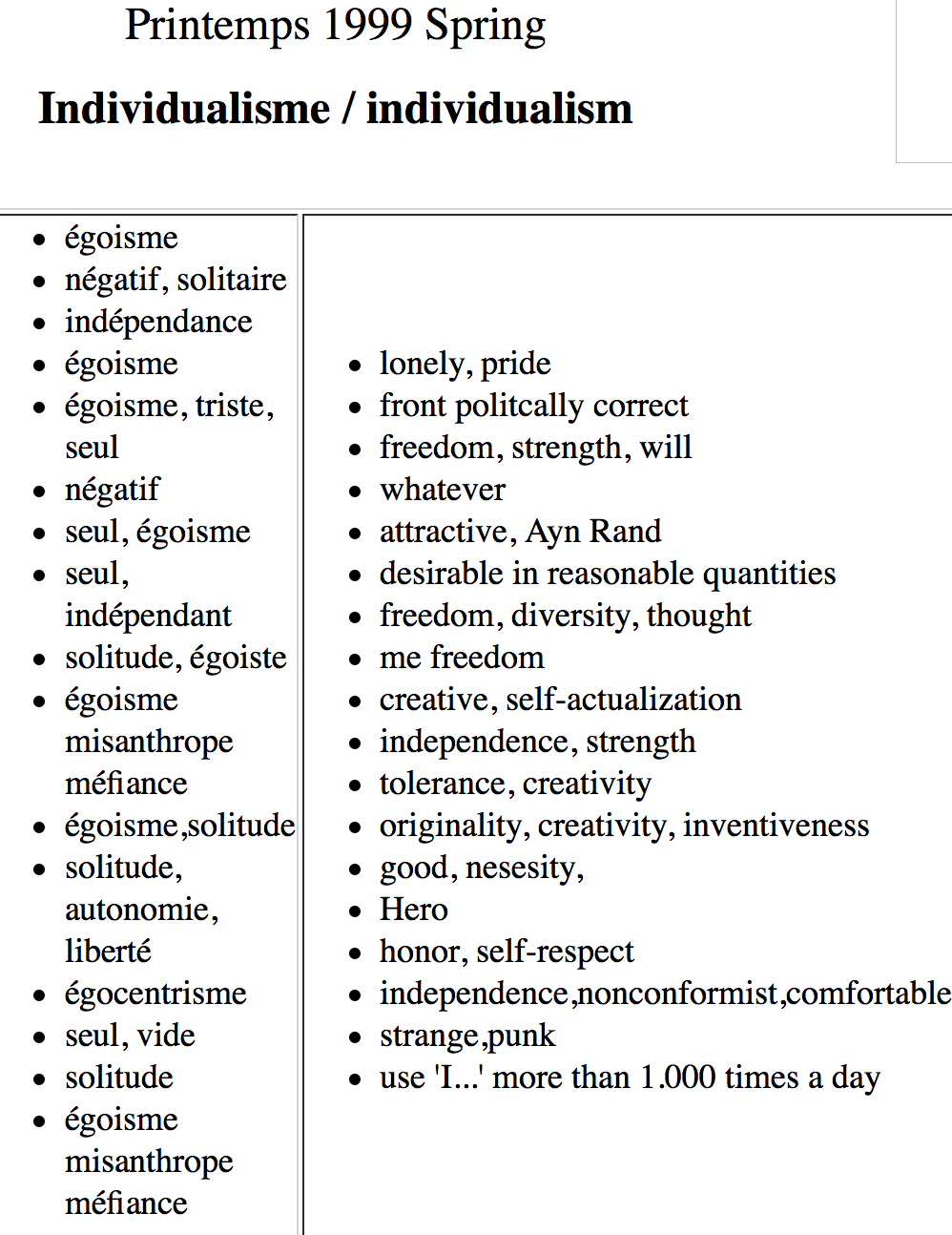

In cross-cultural encounters involving different languages, there may be quite different interpretations of commonly used words or phrases. The Cultura project, originating at the Massachusetts Institute of technology, connects students from different cultures with the aim of improving both language proficiency and cross-cultural understanding. The relationship between groups from different universities begins with the students completing on each side questionnaires in which they give their interpretations of particular expressions, such as “family” or “liberty”. Some words have elicited quite different associations from groups in the US and in France. The word “individualism” (French, individualisme), for example, among the US students was associated with positive qualities of the individual being independent, free and unfettered in thought and action. The French understanding was someone different; the word was associated most commonly with egotism and isolation. This led to some interesting online discussions between the two groups of students (see Furstenberg et al., 2001). If we assume word meanings carry accurately across languages – a misperception common among monolinguals – this has the potential to result in misunderstandings.

In some cases, particular words may be associated with political orientations. The Republican Party in the US, for example, is likely to see “freedom” as a major component of the party’s belief system, associated in their case especially with the ability to bear arms unencumbered by laws and with the absence of government interference in conducting business transactions. A quite divergent view of the word “freedom” was recounted in Rogers and Steinfatt (1999) in which a Vietnamese woman explained why she felt she could not live in the US:

The meaning of any value, including freedom, differs across cultures. An old woman in Saigon told one of the authors that she felt that she could not tolerate the lack of freedom in the United States. In Vietnam she was free to sell her vegetables on the sidewalk without being hassled by police or city authorities. She did not have to get a permit to fix the roof on her house. She had the freedom to vote for a communist candidate if she wanted to. She believed that in the United States, where her children lived, people were expected to tell others what they thought. In Vietnam she had the freedom to remain silent. Her perceptions determined her behavior; she refused to immigrate to the United States to join her children (p. 84).

Adhering rigidly to one’s own interpretation of a word with strong social significance can be problematic. The symbolic value of certain phrases may be incorporated into our belief system and form an essential element of how we see the world. There are particular phrases which trigger strong positive or adverse reactions. Countering someone advocating a very different interpretation of such a phrase may be perceived as a personal attack, a denial of an aspect of the other’s identity. A coal miner, for example, is likely to react quite differently to the phrase “global warming” than an environmental activist. Those views may center around potential unemployment, resulting in loss of income, family tension, and potentially a dramatic change in lifestyle. In such a situation, asserting the reality of global warming through environmental science, case studies, or climate statistics is likely to fall on deaf ears. Communication is likely to be impeded. As Alan Alda posits in a book on communication between scientists and the public (2017), one might in such circumstances try to find commonalities in other areas such as similarities in personal backgrounds, regional affiliation, or religion.

Conflicts and language

Conflict can arise over differences of opinion regarding substantive issues such as global warming. On the other hand, they may derive from misunderstandings based on verbal or nonverbal communication tied to cultural norms and values. These can be minor – such as not performing a given greeting appropriately – or more serious – such as perceived rudeness based on how a request has been formulated. Missteps in most forms of nonverbal communication can typically be easily remedied (through observation and imitation) and normally do not pose major sources of conflict. Non-natives in most cases will not be expected to be familiar with established rituals. Most Japanese, for example, will not expect Westerners to have mastered the complexities of bowing behavior, which relies on perceptions of power/prestige differentials unlikely for a foreigner to perceive in the same way as native Japanese.

Similarly, non-natives will be forgiven making errors and speaking in areas of grammar, vocabulary, or pronunciation. Russians will not expect non-natives to have mastered the complex set of inflections that accompany different grammatical cases. Native Chinese will not expect a mastery of tones. Of course, if the errors interfere with intelligibility, there will be problems in communicative effectiveness. There may be, as we have discussed, some prejudice and possible discrimination against those who do not have full command of a language or who speak with a noticeable foreign accent. Conflict is less likely to come from language mechanics and more likely from mistakes in language pragmatics, most frequently in the area of speech acts, i.e. using language to perform certain actions or to have them performed by others. Native English speakers, for example, will typically qualify requests by prefacing them with verbs such as “would you” or “could you”, as in the following:

“Could I please have another cup of tea?”

“Would you pass the ketchup when you’re through with it?”

The use of the modal verb “could” or the conditional form “would” is not semantically necessary – they don’t add anything to the meaning. They are included as part of the standard way polite requests are formulated in English. Asking the same questions more directly, i.e. “Bring me another cup of tea”, would be perceived as abrupt and impolite. Yet, in many cultures, requests to strangers might well be formulated in such a direct way. Languages as different from one another as German and Chinese are both more direct in formulating requests. Non-native English speakers might will transfer those formulations from their native language word-for-word into English, leading to a possible perception of rudeness. This is known as pragmatic transfer, discussed in chapter four.

Confusion or conflict can arrive in some cases from differences in tone or intonation. Donal Carbaugh (2005) gives an example, based on work done by John Gumperz:

As East Asian workers in a cafeteria in London served English customers, they would ask the customers if they wanted “gravy” [sauce], but asked with falling rather than rising intonation. While this falling contour of sound signaled a question in Hindi, to English ears it sounded like a command. The servers thus were heard by British listeners to be rude and inappropriately bossy, when the server was simply trying to ask, albeit in a Hindi way, a question. In situations like these, one’s habitual conversational practices can cue unwitting misunderstandings, yet those cues are typically beyond the scope of one’s reflection. As a result, miscommunication is created, but in a way that is largely invisible to participants. Once known to them, communication can take a different form. (pp. 22-23)

This source of conflict, a misperception of another person’s actions or intent, here attributing rudeness to a difference in communication style, is one of the more common occurrences in both everyday interactions and in cross-cultural encounters. How such conflicts are resolved varies in line with the context and individuals concerned. Communication scholars have identified patterns in conflict resolution, discussed in the next section.

Conflict resolution

Conflict resolution styles represent processes and outcomes based on the interests of the parties involved.

If I am intent on reaching my own goals in an encounter, I use what’s called a dominating or controlling style. This is most often associated with cultures labeled individualistic, as it involves one individual’s will winning over another’s. On the other hand, if I am content to allow others to get their way, I use an obliging or yielding style. This is often related to cultures deemed collectivistic, as it favors harmony over outcome. Stella Ting-Toomey (2015) has been a leading scholar in this area, with explorations of how to predict a given conflict resolution style based on national cultures. But she cautions, as do others, how dependent individual behavior is on the specific context and on the willingness and ability of the parties to be flexible and compromising. Flexibility and openness might lead to the adoption of an integrating or collaborating approach, seeking to find a solution that satisfies both parties. A compromising approach provides a negotiated outcome which necessitates each party giving up something in order to reach a solution that provides partial gains on each side. Avoidance or withdrawal may be appropriate if no resolution is likely, or there is not enough time or information to resolve the conflict.

Examples of conflict resolution styles associated with different cultural orientations are given in Markus & Lin (1999). They point out that in the US the predominate perspective traditionally has been that represented by European-American views: “Having one’s own ideas and the courage of one’s convictions, making up one’s own mind and charting one’s own course are powerful public meanings inscribed in everyday social practices” (p. 307). That tends to translate into the importance of asserting one’s position in a conflict, rather than seeking compromise or accommodation:

Within a world organized according to the tenets of individualism and animated by the web of associated understandings and practices, any perceived constraint on individual freedom is likely to pose immediate problems and require a response. Typically the most appropriate response in a conflict situation involves a direct or honest expression of one’s ideas. Indeed, it is sometimes the individualist’s moral imperative, the sign that one is being a “good” person, to disagree with and remain unmoved by the influence of others. The right to disagree, typically manifested by a direct statement of one’s own views, can create social difficulties, but it is understood and experienced as a birthright (p. 308).

The authors point out that this perspective is far from being shared with the rest of the world, and in fact, is not universal within the US. Asian-American, African-American, and Hispanics are likely to have quite different views regarding conflict, identified by the author as an interdependent perspective: “From an interdependent perspective, the underlying goal of social behavior is not the preservation and manifestation of individual rights and attributes, but rather the preservation of relationships” (p. 311). In this approach, individual rights are superseded by group interest. Quick, decisive conflict resolution is not the ultimate goal, but rather an outcome that serves all parties and preserves harmony. In many communities that involves the use of mediators. In a study of “peaceful societies”, Bonta (1996) describes how such figures play a key role in cultures in which violence is rare. As an effective approach for resolving conflict in cross-cultural situations, Markus & Lin (1999) advocate the use of face negotiation techniques, as outlined below.

The concept of face

Ting-Toomey has been in the forefront in the development of a theory often applied to intercultural conflict, called face negotiation theory (Ting-Toomey & Kurogi ,1998). This theory tries to explain conflict using the concept of face, often defined as a person’s self-image or the amount of respect or accommodation a person expects to receive during interactions with others. Ting-Toomey actually differentiates among three different concepts of face:

Self-face: The concern for one’s image, the extent to which we feel valued and respected.

Other-face: Our concern for the other’s self-image, the extent to which we are concerned with the other’s feelings

Mutual-face: Concern for both parties’ face and for a positive relationship developing out of the interaction

According to face negotiation theory, people in all cultures share the need to maintain and negotiate face. Some cultures – and individuals – tend to be more concerned with self-face, often associated with individualism. Conflict resolution in this case may become confrontational, leading potentially to a loss of face for the other party. Collectivists – cultures or individuals – tend to be more concerned with other-face and may use strategies such as avoidance, the use of intermediaries, or withdrawal. They may also engage in mutual facework (actions to uphold face) such as negotiating, following up in a private conversation, or apologizing.

Face concerns can appear in all kinds of interactions, but mostly come to the fore during conflicts of one kind or another. Ting-Toomey predicts that certain cultures will have a preference for a given conflict style based on face concerns. Individualistic cultures or individuals will prefer a direct way of addressing conflicts, according to the chart presented earlier, a dominating style or, optimally, a collaborating approach. The latter, however, requires that one address a conflict directly, something which particular cultures or people may prefer not to do. Collectivistic cultures or individuals may prefer an indirect approach, using subtle or unspoken means to deal with conflict (avoiding, withdrawing, compromising), so as not to challenge the face of the other.

Another way to view conflict styles resolution is through the Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory developed by Mitchell Hammer (2005). According to the theory behind the inventory, disagreements leading to conflict have two dimensions, an affective (emotional) and a cognitive (intellectual or analytical) side. According to Hammer, parties in a conflict experience an emotional response based on the disagreement, its perceived cause, and the threat they see it as posing. How the two parties interact he sees as dependent on how emotionally expressive they tend to be and how direct their communication styles are. This results in four different styles, Discussion (direct communication style while being emotionally reserved), Engagement (also direct but expressive emotionally), Accommodating (indirect communication style, emotionally relaxed) and Dynamic (indirect communication style, while emotionally involved). Hammer developed an instrument that measures these four styles and argues that being able to identify your own style and that of your counterpart can help better manage conflict.

One of the important ways to avoid conflict in personal encounters is to be attentive to what the other person is communicating, not just through the words spoken, but through body language and other nonverbal means. The process of active listening can be quite helpful. Rogers and Steinfatt (1999) outline some of the important factors in doing that:

Active listening consists of five steps: (1) hearing, or exposure to the message, (2) understanding, when we connect the message to what we already know, (3) remembering, so that we do not lose the message content, (4) evaluating, thinking about the message and deciding whether or not it is valid, and (5) responding, when we encode a return message based on what we have heard and what we think of it (p. 158).

What is conflict good for?

Conflict has many positive functions. It prevents stagnation, it stimulates interest and curiosity. It is the medium through which problems can be aired and solutions arrived at. It is the root of personal and social change. And conflict is often part of the process of testing and assessing oneself. As such it may be highly enjoyable as one experiences the pleasure of the full nd active use of one’s capacities. In addition, conflicts demarcate groups from one another and help establish group and personal identities.

Deutsch, 1987, p. 38

Despite our best intentions as well as engaging in the techniques for optimizing cross-cultural encounters, conflict is sometimes unavoidable. Scholars of conflict resolution have in fact pointed to some positive aspects of personal conflict (see sidebar). Conflicts can illuminate key cultural differences and thus can offer “rich points” for understanding other cultures.

Cultural schemas

When conflicts occur in personal encounters, an awareness of the dynamics of conflict resolution can be helpful in resolving issues. It is useful as well to have some awareness of the nature and origins of our social behavior. If we assume that the way our culture operates is the default human behavior worldwide, we are likely to reject alternatives as unnatural and inferior. In reality, what we experience as “common-sense” or “normal” behavior is socially constructed and learned. The kind of taken-for-granted knowledge of how things work becomes automatic, not requiring any conscious thought. We can think of such behavior as cultural schemas (set patterns of behavior and language) which are typically learned by observing others or performing an action once. Holliday, Hyde & Kullman (2004) describe how this works:

Drinking in a Spanish bar or an English pub: not the same

In Spain the schema may be: enter the bar and greet the people there with a general ‘Buenos dias’, go to the bar; see if there are any friends around; offer to get them drinks; order the drinks at the bar; drink and accept any offers of other drinks from others; when you want to go ask how much you owe, often clarifying with the barman/woman which drinks you are responsible for; make sure you say goodbye to everyone you know and to those you don’t with a general ‘Hasta luego.’ A Spanish man greeting strangers in a bar in England would probably be disappointed in the lack of reciprocity of his greeting. The locals would be suspicius or amused; the Spaniard would feel the locals are perhaps unfriendly. He may be seen as dishonest or evasive if he doesn’t offer to pay for the first drink he asks for upon being served that drink. An Englishman entering a Spanish bar may be seen as a little odd or ingenuine if he uses ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ all the time. These terms tend to be reserved for asking favours and for having rendered a favour, and are thus not used so ‘lightly’.

Holliday, Hyde & Kullman (2004), p. 199

Knowing the cultural schema of events such as dancing a salsa or ordering a meal in McDonald’s, is derived from empirical experience of that ‘event’. It is reinforced each time that it serves as a useful guide for behaviour in that particular context or ‘genre’. Of course the schemas of these different genres can be very different in different countries…The problem is that if we have a schema for an event already established in our national, regional or ethnic cultural milieu, we are likely to make the error of thinking that the event in the other culture should be the same – or similar. When expectations are upset one may experience a certain degree of shock that can perhaps translate into resentment, anger and perhaps negative judgement of the other culture. This is because expectations have not been fulfilled and one may therefore feel vulnerable and ‘adrift’ (pp. 197-8).

In our everyday lives in our own cultures, we carry out tasks routinely and without thinking. This leads to a sense that such behavior is universal. Being confronted with alternative models can be upsetting. The authors give an example in the contrast between visiting a pub in Britain and a bar in Spain (see sidebar). The example shows that we have to rebuild our schemas in different cultures, in order to navigate our way successfully through new cultural situations.

Sometimes the cultural schema relies on a sequence of actions, as in a British pub, or it may be primarily related to language use. Sharifian (2005) illustrates how a particular Persian cultural schema known as sharmandegi (sometimes translated as ‘being ashamed’) is rendered in a number of speech acts:

Expressing gratitude: ‘You really make me ashamed’

Offering goods and services: ‘Please help yourself, I’m ashamed, it’s not worthy of you.’

Requesting goods and services: ‘I’m ashamed, can I beg some minutes of your time.’

Apologizing: ‘I’m really ashamed that the noise from the kids didn’t let you sleep.’

(p. 125)

Sharifian suggests that in all cases, the sharmandegi schema “seems to encourage Iranians to consider the possibility that in the company of others they may be doing or have done something wrong or something not in accordance with the other party’s dignity” (p. 125). According to the analysis by Bowe and Martin’s introduction to intercultural communication (2007):

Sharifian relates the sharmandegi schema to a higher level ‘overarching’ cultural schema which defines a core value of culture related to social relations that he calls “adab va ehteram”, roughly glossed as ‘courtesy and respect’ in English. He suggests that ‘(t)his higher-level schema encourages Iranians to constantly place the presence of others at the centre of their conceptualizations and monitor their own ways of thinking and talking to make them harmonious with the esteem that they hold for others’. (p. 42)

Another way to formulate this is that one needs to learn the special discourse of the cultural event or action. Discourse often refers to specialized language use (as in the discourse of airline pilots) but in postmodern use it often is used to go beyond language. J.P. Gee (1999) describes discourse as “different ways in which we humans integrate language with non-language ‘stuff,’ such as different ways of thinking, acting, interacting, valuing, feeling, believing, and using symbols, tools, and objects in the right places and at the right times so as to enact and recognize different identities and activities” (p. 13). According to Gee, discourses are embedded into social institutions and often involve the use of various “props” like books, tools, or technologies. One might need a whole host of resources in any given context to come up with an appropriate discourse strategy, involving use of an appropriate language register, expressing the correct politeness formulas, wearing the right clothing, using appropriate body language, etc.

Mediated encounters

Experiencing other cultures can happen through personal encounters or travel, but it can also be a mediated experience, in which we are experiencing new cultures vicariously or virtually. This might be at a fairly superficial level, through reading or watching news reports dealing with other countries. Of course, news from abroad is highly selective, often focusing on dramatic or disastrous events, inevitably filtered through the lens of the reporter’s own culture. We tend to gain little insight into day-to-day lives through the nightly news. More in-depth information may be supplied by longer written pieces in serious newspapers/magazines or the Internet, or through TV or documentaries. We can’t travel everywhere or have the opportunity to meet an endless number of people from diverse cultures. From that perspective, the second-hand information we obtain from mass media can provide basic knowledge and starting points for serious study.

More informed views come from first-hand accounts of encounters or from personal cultural trajectories. Of particular interest are what are sometimes called language autobiographies, in which others recount their process of adapting linguistically and culturally to a new environment. An excellent example is Eva Hoffman’s memoir Lost in Translation: A Life in a New Language (1989). She recounts her early life, moving with her family from Poland to the US when she was a child. One of the early significant cultural experiences she had was a change of her name and that of her sister from Ewa and Alina to “Eva” and “Elaine”:

Nothing much has happened, except a small, seismic mental shift. The twist in our names takes them a tiny distance from us – but it’s a gap into which the infinite hobgoblin of abstraction enters. Our Polish names didn’t refer to us; they were as surely us as our eyes or hands. These new appellations, which we ourselves can’t yet pronounce, are not us. They are identification tags, disembodied signs pointing to objects that happen to be my sister and myself…[They] make us strangers to ourselves. (p. 105)

The change may seem a small matter, but for Hoffman it represents a separation from how she sees her place in the world. She has become someone unfamiliar to herself, with a name she cannot even pronounce correctly. Eventually, she finds herself in a kind of linguistic and psychological no-man’s land, between two languages:

I wait for that spontaneous flow of inner language which used to be my nighttime talk with myself…Nothing comes. Polish, in a short time, has atrophied, shriveled from sheer uselessness. Its words don’t apply to my new experiences, they’re not coeval with any of the objects, or faces, or the very air I breathe in the daytime. In English, the words have not penetrated to those layers of my psyche from which a private connection could proceed. (p. 107)

She has difficulty ordering and making sense of the events of her life. Slowly she begins a reconstruction of herself in English. Initially, this comes through listening and imitating:

All around me, the Babel of American voices, hardy midwestern voices, sassy New York voices, quick youthful voices, voices arching under the pressure of various crosscurrents…Since I lack a voice of my own, the voices of others invade me as if I were a silent ventriloquist. They ricochet within me, carrying on conversations, lending me their modulations, intonations, rhythms. I do not yet possess them; they possess me. But some of them satisfy a need; some of them stick to my ribs… Eventually, the voices enter me; by assuming them, I gradually make them mine. (pp. 219-220)

Step-by-step, Hoffman learns both the verbal and nonverbal codes, and can adapt to US cultural schemas:

This goddamn place is my home now…I know all the issues and all the codes here. I’m as alert as a bat to all subliminal signals sent by word, look, gesture. I know who is likely to think what about feminism and Nicaragua and psychoanalysis and Woody Allen…When I think of myself in cultural categories – which I do perhaps too often – I know that I’m a recognizable example of a species: a professional New York woman…I fit, and my surroundings fit me (pp. 169–170).

An account like that of Hoffman’s provides a detailed, insider’s story of cultural adaptation. Both fiction and nonfiction can supply insights into individual lives, which puts a human face on the theories of cultural encounters. This is true of films as well. Life stories convey the emotional turmoil that often accompany cultural transitions, something we sometimes lose track of in scholarly studies.

Theory first postulated by stella ting-toomey to explain how different cultures manage conflict.

Favorable social impression that a person wants others to have of him or her.

Seeking one's own interest during conflict (primary interest in individualistic cultures).

Paying attention to the needs and desires of the other party in a conflict.

Respect and dignity of the group as a whole (primary interest in collectivistic cultures).

Behaviors or messages (verbal or non-verbal) that maintain, restore, or save face.

The familiar and pre-acquainted knowledge one uses when entering a familiar situation in his/her own culture.

Conventionally, the use of words to exchange thoughts and ideas; in postmodern terms, a mode of organizing knowledge, ideas, or experience that is rooted in language and its concrete contexts.