18 Organization of Life

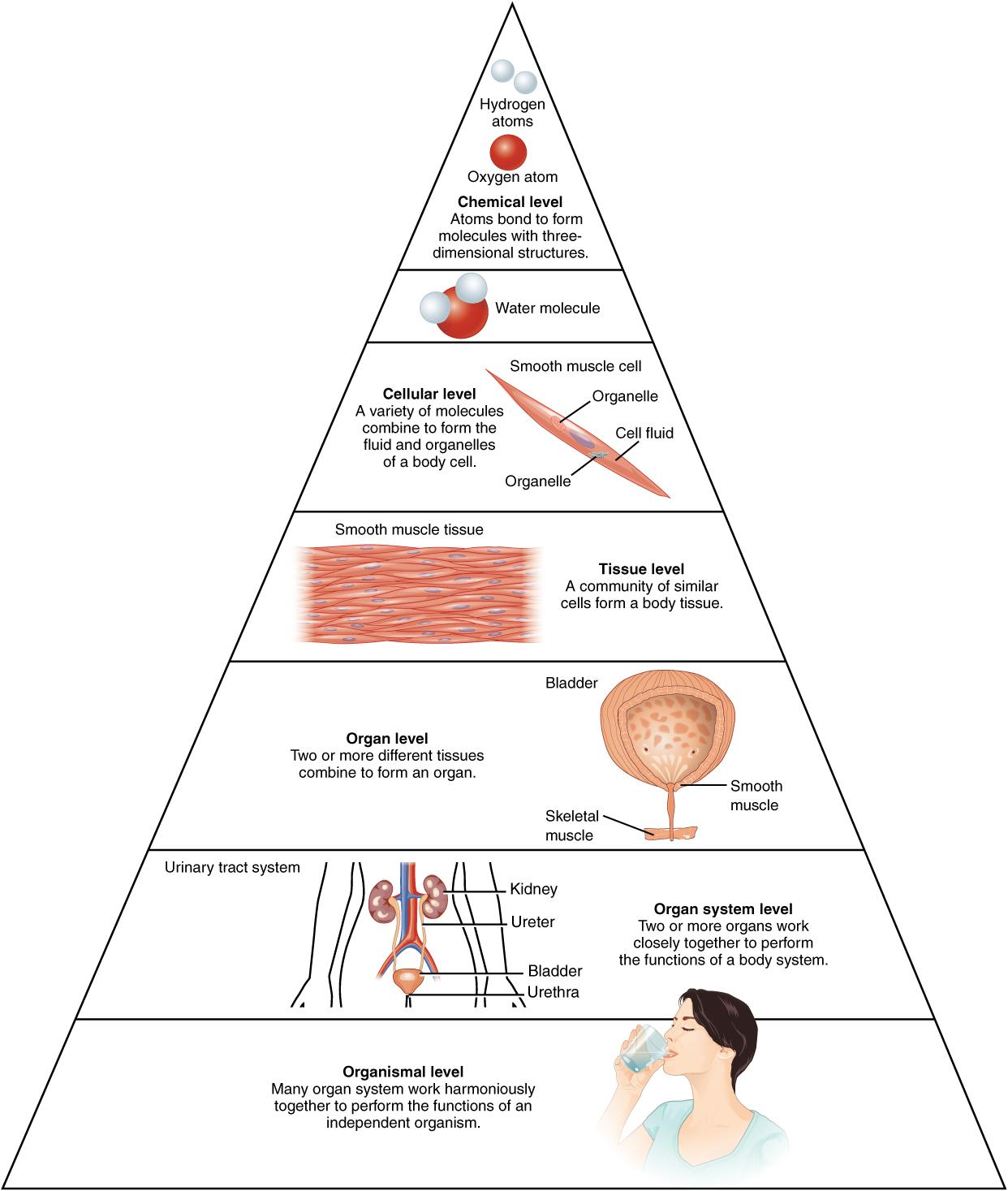

Before you begin to study the different structures and functions of the human body related to nutrition, it is helpful to consider the basic architecture of the body; that is, how its smallest parts are assembled into larger structures. It is convenient to consider the structures of the body in terms of fundamental levels of organization that increase in complexity: atoms, molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organ systems, and organisms. Higher levels of organization are built from lower levels. Therefore, atoms combine to form molecules, molecules combine to form cells, cells combine to form tissues, tissues combine to form organs, organs combine to form organ systems, and organ systems combine to form organisms (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Levels of structural organization of the human body. The organization of the body often is discussed in terms of distinct levels of increasing complexity, from the smallest chemical building blocks to a unique human organism.

The Levels of Organization

Consider the simplest building blocks of matter: atoms and molecules. In Unit 1, you had an introduction to atoms and molecules. Remember, all matter in the universe is composed of one or more unique elements, such as hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen. The smallest unit of any of these elements is an atom. Atoms of individual elements combine to make molecules, and molecules bond together to make bigger macromolecules. Four macromolecules—carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids (e.g., DNA, RNA)—make up all of the structural and functional units of cells.

The Basic Structural and Functional Unit of Life: The Cell

Cells are the most basic building blocks of life. All living things are composed of cells. New cells are made from preexisting cells, which divide in two. Who you are has been determined because of two cells that came together inside your mother’s womb. The two cells containing all of your genetic information (DNA) fused to begin the development of a new organism. Cells divided and differentiated into other cells with specific roles that led to the formation of the body’s numerous organs, systems, blood, blood vessels, bones, tissues, and skin. While all cells in an individual contain the same DNA, each cell only expresses the genetic codes that relate to that cell’s specific structure and function.

As an adult, you are made up of trillions of cells. Each of your individual cells is a compact and efficient form of life—self-sufficient, yet interdependent upon the other cells within your body to supply its needs. There are hundreds of types of cells (e.g., red blood cells, nerve cells, skin cells). Each individual cell conducts all the basic processes of life. It must take in nutrients, excrete wastes, detect and respond to its environment, move, breathe, grow, and reproduce. Many cells have a short life span and have to be replaced continually. For example, enterocytes (cells that line the intestines) are replaced every 2-4 days, and skin cells are replaced every few weeks.

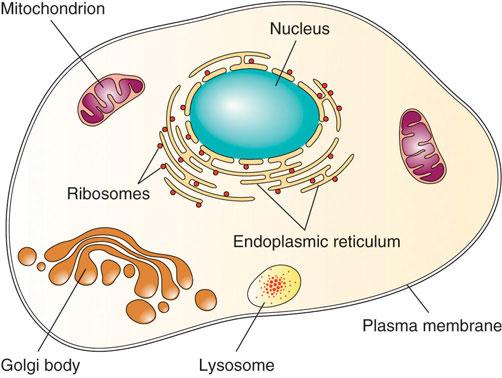

Although a cell is defined as the “most basic” unit of life, it is structurally and functionally complex (Figure 3.2). A human cell typically consists of a flexible outer cell membrane (also called a plasma membrane) that encloses cytoplasm, a water-based cellular fluid, together with a variety of functioning units called organelles. The organelles are like tiny organs constructed from several macromolecules bonded together. A typical animal cell contains the following organelles:

- Nucleus: houses genetic material (DNA)

- Mitochondria: often called the powerhouse of the cell, generates usable energy for the cell from energy-yielding nutrients

- Ribosomes: assemble proteins based on genetic code

- Endoplasmic reticulum: processes and packages proteins and lipids

- Golgi apparatus (golgi body): distributes macromolecules like proteins and lipids around the cell

- Lysosomes: digestive pouches which break down macromolecules and destroy foreign invaders

Figure 3.2. The cell structure

Tissues, Organs, Organ Systems, and Organisms

A tissue is a group of many similar cells that share a common structure and work together to perform a specific function. There are four basic types of human tissues: connective tissue, which connects tissues; epithelial tissue, which lines and protects organs; muscle, which contracts for movement and support; and nerve, which responds and reacts to signals in the environment.

An organ is a group of similar tissues arranged in a specific manner to perform a specific physiological function. Examples include the brain, liver, and heart. An organ system is a group of two or more organs that work together to perform a specific physiological function. Examples include the digestive system and central nervous system.

There are eleven distinct organ systems in the human body (Figure 3.3). Assigning organs to organ systems can be imprecise since organs that “belong” to one system can also have functions integral to another system. In fact, many organs contribute to more than one system. And most of these organ systems are involved in nutrition-related functions within the body (Table 3.1). For example, the cardiovascular system plays a role in nutrition by transporting nutrients in the blood to the cells of the body. The endocrine system produces hormones, many of which are involved in regulating appetite, digestive processes, and nutrient levels in the blood. Even the reproductive system plays a role in providing nutrition to a developing fetus or growing baby.

Figure 3.3. Organ systems of the human body

|

Cardiovascular |

Heart, blood vessels, blood |

Transport oxygen, nutrients, and waste products |

|

Digestive |

Mouth, esophagus, stomach, intestines, salivary glands, pancreas, liver and gallbladder |

Digestion and absorption |

|

Endocrine |

Endocrine glands (e.g., thyroid, ovaries, pancreas) |

Produce and release hormones, regulate nutrient levels |

|

Lymphatic |

Lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, thymus gland, spleen |

Fluid balance, defend against pathogens |

|

Integumentary |

Skin, nails, hair, sweat glands |

Protection, body temperature regulation |

|

Muscular |

Skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscle |

Body movement |

|

Nervous |

Brain, spinal cord, nerves |

Interpret and respond to stimuli, appetite control |

|

Reproductive |

Gonads, genitals |

Reproduction and sexual characteristics |

|

Respiratory |

Lungs, nose, mouth, throat, trachea |

Gas exchange (oxygen and carbon dioxide) |

|

Skeletal |

Bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, joints |

Structure and support, calcium storage |

|

Urinary |

Kidneys, bladder, ureters |

Waste excretion, water balance |

Table 3.1. The eleven organ systems in the human body and their major functions

An organism is the highest level of organization—a complete living system capable of conducting all of life’s biological processes. In multicellular organisms, including humans, all cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems of the body work together to maintain the life and health of the organism.

Self-Check:

Attributions:

- Rice University, “Anatomy and Physiology” CC BY 4.0

- University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program, “Basic Biology, Anatomy, and Physiology” CC BY-NC 4.0

Images:

- Figure 3.1. “Levels of Structural Organization of the Human Body” by OpenStax, Rice University is licensed under CC BY 4.0

- Figure 3.2. “The Cell Structure” by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Figure 3.3. “Organ Systems of the Human Body” by OpenStax, Rice University is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- Table 3.1. “The organ systems in the human body and their major functions” by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The smallest structural and functional units of all living things.

A thin covering around the cell that separates the internal and external environments.

The cellular fluid within a cell.

Tiny organs within the cell that perform a specific task for the cell.

A membrane-bound organelle within the cell that contains genetic material (DNA).

An organelle often called the powerhouse of the cell; generates usable energy for the cell from energy-yielding nutrients.

An organelle that assembles proteins based on the instructions of DNA.

An organelle that processes and packages proteins and lipids for transport.

An organelle that distributes macromolecules like proteins and lipids around the cell.

An organelle that breaks down macromolecules and destroys foreign invaders.

A group of many similar cells that share a common structure and work together to perform a specific function.

A tissue that connects, supports, and/or binds other tissues in the body.

A tissue that lines and protects organs.

A tissue that contracts to provide movement and support.

A tissue that responds and reacts to signals in the environment.

A group of similar tissues arranged in a specific manner to perform a specific physiological function (e.g., the heart, the lungs).

A group of two or more organs that work together to perform a specific physiological function (e.g., the digestive system, the central nervous system).

The highest level of organization; a complete living system capable of conducting all of life’s biological processes.