25 Fiber – Types, Food Sources, Health Benefits, and Whole Versus Refined Grains

Dietary fiber is defined by the Institute of Medicine’s Food and Nutrition Board as “nondigestible carbohydrates and lignin that are intrinsic and intact in plants.” Fiber plays an important role in giving plants structure and protection, and it also plays an important role in the human diet.

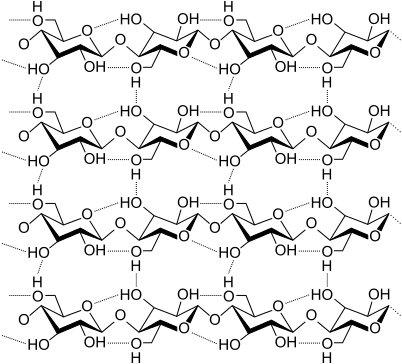

Cellulose is one type of fiber. The chemical structure of cellulose is shown in the figure below, with our simplified depiction next to it. You can see that cellulose has long chains of glucose, similar to starch, but they’re stacked up, and there are hydrogen bonds linking the stacks. The special bonds between these glucose units in fiber are not enzymatically digested in the digestive tract, and therefore, fiber passes undigested to the colon or large intestine.

Figure 4.22. The chemical structure of cellulose, and a simplified illustration of cellulose.

You might be wondering how fiber has any benefit to us if we can’t digest it. However, it doesn’t just pass through the digestive tract as a waste product. Instead, it serves many functions on its journey, and these contribute to our health. Let’s explore the different types of fiber, where we find them in foods, and what benefits they provide!

Types of Fiber

Whole plant foods contain many different types of molecules that fit within the definition of fiber. One of the ways that types of fiber are classified is by their solubility in water. Whole plant foods contain a mix of both soluble and insoluble fiber, but some are better sources of one than the other.

- Soluble Fiber – These fibers dissolve in water, forming a viscous gel in the GI tract, which helps to slow digestion and the absorption of glucose. This means that including soluble fiber in a meal helps to prevent sharp blood sugar spikes, instead making for a more gradual rise in blood glucose. Consuming a diet high in soluble fiber can also help to lower blood cholesterol levels, because soluble fiber binds cholesterol and bile acids (which contain cholesterol) in the GI tract. Soluble fiber is also highly fermentable, so it is easily digested by bacteria in the large intestine. Pectins and gums are common types of soluble fibers, and good food sources include oat bran, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, peas, and some fruits and vegetables. (Psyllium fiber supplements like Metamucil are composed mainly of soluble fiber, so if you’ve ever stirred a spoonful of this into a glass of water, you’ve seen the viscous consistency characteristic of soluble fiber.)

- Insoluble Fiber – These fibers typically do not dissolve in water and are nonviscous. Some are fermentable by bacteria in the large intestine but to a lesser degree than soluble fibers. Insoluble fibers help prevent constipation, as they create a softer, bulkier stool that is easier to eliminate. Lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose are common types of insoluble fibers, and food sources include wheat bran, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

Food Sources of dietary fiber

Since fiber provides structure to plants, fiber can be found in all whole plant foods, including whole grains (like oatmeal, barley, rice and wheat), beans, nuts, seeds, and whole fruits and vegetables.

Figure 4.23. A bowl of oatmeal topped with blueberries and sunflower seeds.

This meal is packed with fiber from the oatmeal, blueberries, and sunflower seeds.

When foods are refined, parts of the plant are removed, and during this process, fiber and other nutrients are lost. For example, fiber is lost when going from a whole fresh orange to orange juice. A whole orange contains about 3 grams of fiber, whereas a glass of orange juice has little to no fiber. Fiber is also lost when grains are refined. We will discuss this more a little later.

Take a look at the list of foods below to see the variety of foods which provide dietary fiber.

|

Food |

Standard Portion Size |

Calories in Standard Portion |

Dietary Fiber in Standard Portion (g) |

|

Shredded wheat ready-to-eat cereal (various) |

1-1 ¼cup |

155-220 |

5.0-9.0 |

|

Wheat bran flakes ready-to-eat cereal (various) |

¾ cup |

90-98 |

4.9-5.5 |

|

Lentils, cooked |

½ cup |

115 |

7.8 |

|

Black beans, cooked |

½ cup |

114 |

7.5 |

|

Refried beans, canned |

½ cup |

107 |

4.4 |

|

Avocado |

½ cup |

120 |

5.0 |

|

Pear, raw |

1 medium |

101 |

5.5 |

|

Pear, dried |

¼ cup |

118 |

3.4 |

|

Apple, with skin |

1 medium |

95 |

4.4 |

|

Raspberries |

½ cup |

32 |

4.0 |

|

Mixed vegetables, cooked from frozen |

½ cup |

59 |

4.0 |

|

Potato, baked, with skin |

1 medium |

163 |

3.6 |

|

Pumpkin seeds, whole, roasted |

1 ounce |

126 |

5.2 |

|

Chia seeds, dried |

1 Tbsp |

58 |

4.1 |

|

Sunflower seed kernels, dry roasted |

1 ounce |

165 |

3.1 |

|

Almonds |

1 ounce |

164 |

3.5 |

|

Plain rye wafer crackers |

2 wafers |

73 |

5.0 |

|

Bulgur, cooked |

½ cup |

76 |

4.1 |

|

Popcorn, air-popped |

3 cups |

93 |

3.5 |

|

Whole wheat spaghetti, cooked |

½ cup |

87 |

3.2 |

|

Quinoa, cooked |

½ cup |

111 |

2.6 |

Table 4.4. Common foods listed with standard portion size, and calories and fiber in a standard portion.

Although you can get fiber from supplements, whole foods are are a better source, because the fiber comes packaged with other essential nutrients and phytonutrients.

Health Benefits of Dietary Fiber

A high-fiber diet has many benefits, which include:

- Helps prevent constipation. Many fibers (but mostly insoluble fibers) help provide a softer, bulkier stool which is then easier to eliminate.

- Helps maintain digestive and bowel health. Dietary fiber promotes digestive health through its role in supporting elimination and fermentation, and it’s positive impact on gut microbiota. Since fiber provides a bulkier stool, this helps keeps the digestive tract muscles toned and strong which can help prevent hemorrhoids and diverticula.

- Lowers risk of cardiovascular disease. Higher fiber intake has been shown to improve blood lipids by reducing total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low density cholesterol (“bad cholesterol,” associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease), and increasing high density cholesterol (“good cholesterol,” associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease). Higher fiber intake has also been associated with lower blood pressure and reduced inflammation.

- Lowers risk of type 2 Diabetes. Higher fiber intake (especially viscous, or soluble fibers) has been shown to slow down glucose digestion and absorption, benefiting glucose metabolism. A higher fiber diet may also decrease diabetes risk by reducing inflammation.

- Lowers risk of colorectal cancer. More evidence is supporting the idea that higher fiber intake lowers the risk of colorectal cancer, although researchers aren’t sure why. One hypothesis is that dietary fiber decreases transit time (the time it takes for food to move through the digestive tract), thereby exposing the cells of the gastrointestinal tract to carcinogens from food for a shorter time.

- Helps maintain a healthy body weight. Research has shown a relationship between higher dietary fiber intake and lower body weight. The mechanisms for this are unclear, but perhaps high-fiber foods are more filling and therefore keep people satisfied longer with fewer calories. High-fiber foods also tend to be more nutrient-dense compared to many processed foods, which are more energy-dense.

Whole vs. Refined Grains

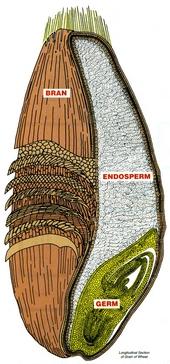

Before they are harvested, all grains are whole grains. They contain the entire seed (or kernel) of the plant. This seed is made up of three edible parts: the bran, the germ, and the endosperm. The seed is also covered by an inedible husk that protects the seed.

Figure 4.24. Wheat growing in a field.

- The bran is the outer skin of the seed. It contains antioxidants, B vitamins and fiber.

- The endosperm is by far the largest part of the seed and provides energy in the form of starch to support reproduction. It also contains protein and small amounts of vitamins and minerals.

- The germ is the embryo of the seed—the part that can sprout into a new plant. It contains B vitamins, protein, minerals like zinc and magnesium, and healthy fats.

Figure 4.25. The anatomy of a wheat kernel which

includes the bran, endosperm, and germ.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans define whole grains and refined grains in the following way:

“Whole Grains—Grains and grain products made from the entire grain seed, usually called the kernel, which consists of the bran, germ, and endosperm. If the kernel has been cracked, crushed, or flaked, it must retain the same relative proportions of bran, germ, and endosperm as the original grain in order to be called whole grain. Many, but not all, whole grains are also sources of dietary fiber.”

Whole grains include foods like barley, corn (whole cornmeal and popcorn), oats (including oatmeal), rye, and wheat. (For a more complete list of whole grains, check out the Whole Grain Council.)

“Refined Grains—Grains and grain products with the bran and germ removed; any grain product that is not a whole-grain product. Many refined grains are low in fiber but enriched with thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, and iron, and fortified with folic acid.”

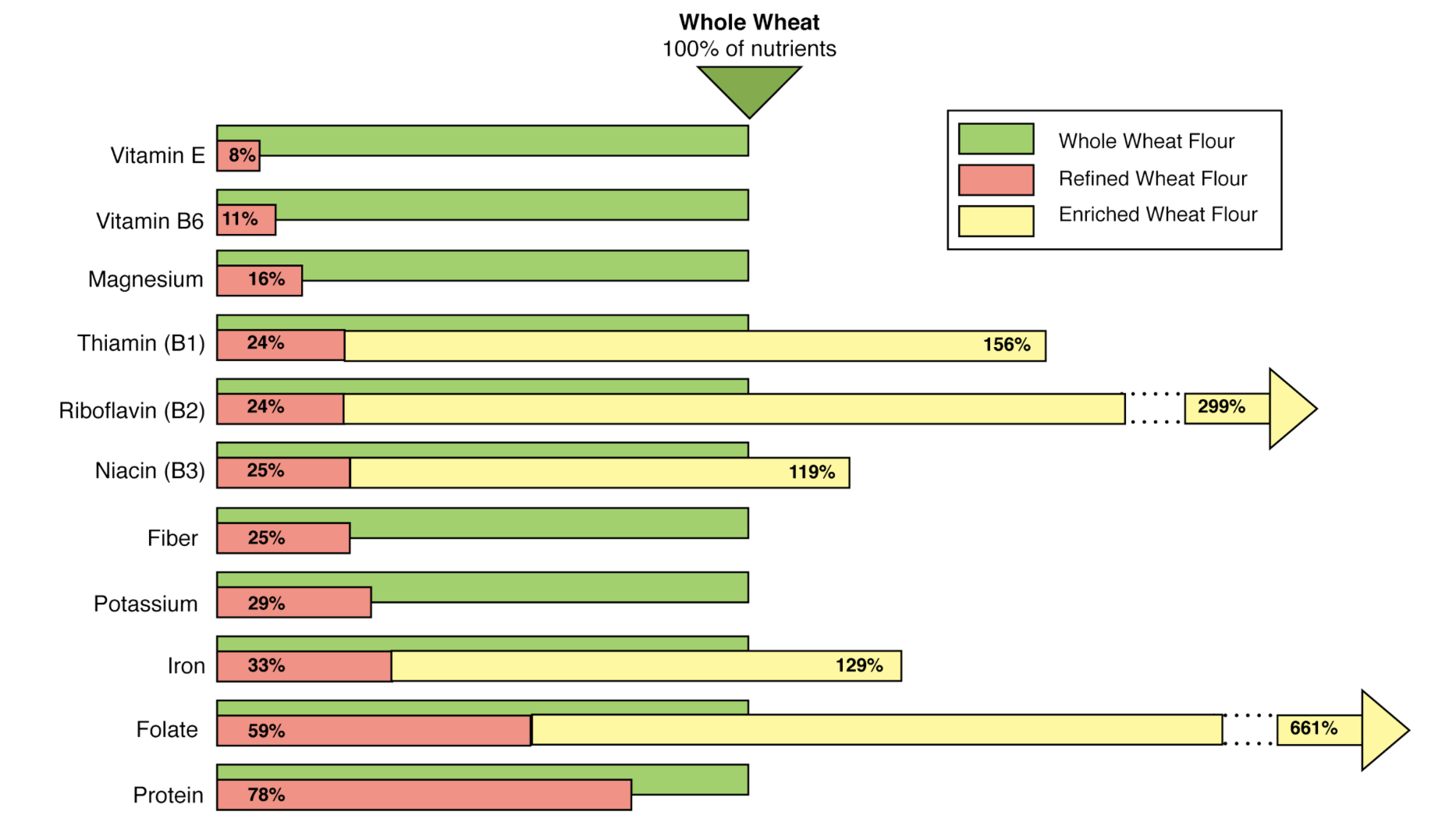

Refined grains include foods like white rice and white flour. According to the Whole Grain Council, “Refining a grain removes about a quarter of the protein in a grain, and half to two thirds or more of a score of nutrients, leaving the grain a mere shadow of its original self.”

Refined grains are often enriched with vitamins and minerals, meaning that some of the nutrients lost during the refining process are added back in after processing. However, many vitamins and minerals are not added back, and neither are the fiber, protein, and healthy fats found in whole grains. In the chart below you can see the differences in essential nutrients between whole wheat flour, refined wheat flour, and enriched wheat flour.

Figure 4.26. The nutrient content of refined wheat and enriched wheat as compared to whole wheat flour.

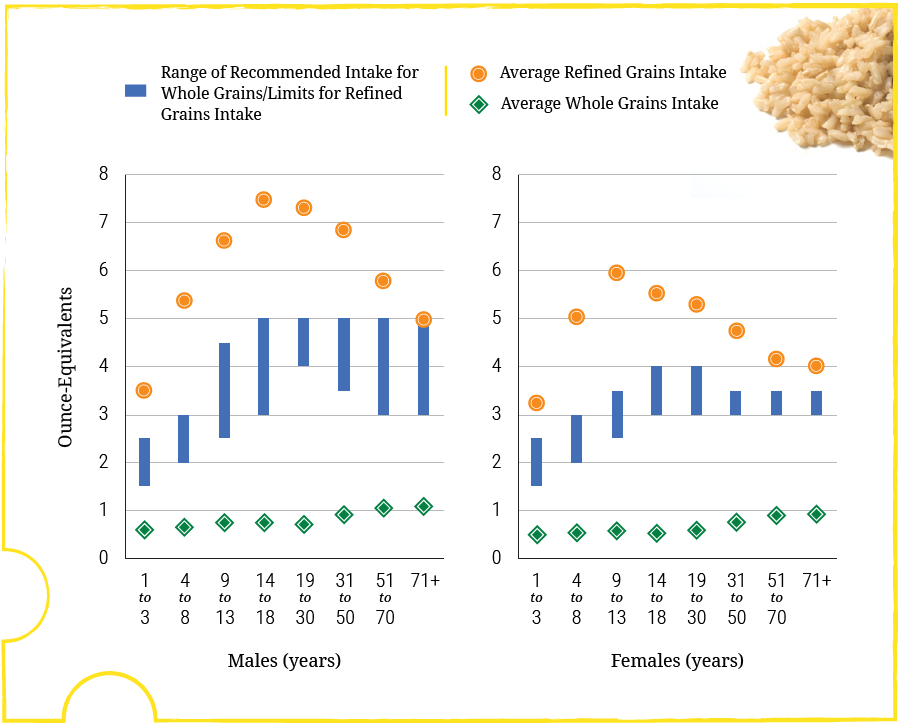

Because whole grains offer greater nutrient density, MyPlate and the Dietary Guidelines recommend that at least half of our grains are whole grains. Yet current data show that while most Americans are eating enough grains overall, they’re eating too many refined grains and not enough whole grains, as shown in this graphic from the Dietary Guidelines:

Figure 4.27. Average Whole & Refined Grain Intakes in Ounce-Equivalents per Day by Age-Sex Groups, Compared to Ranges of Recommended Daily Intake for Whole Grains & Limits for Refined Grains.

Looking for whole grain products at the grocery store can be tricky, since the front-of-package labeling is about marketing and selling products. Words like “made with whole grain” and “multigrain” on the front of the package make it appear like a product is whole grain, when in fact there may be very few whole grains present.

The color of a bread can be deceiving too. Refined grain products can have added caramel color to make them appear more like whole grains.

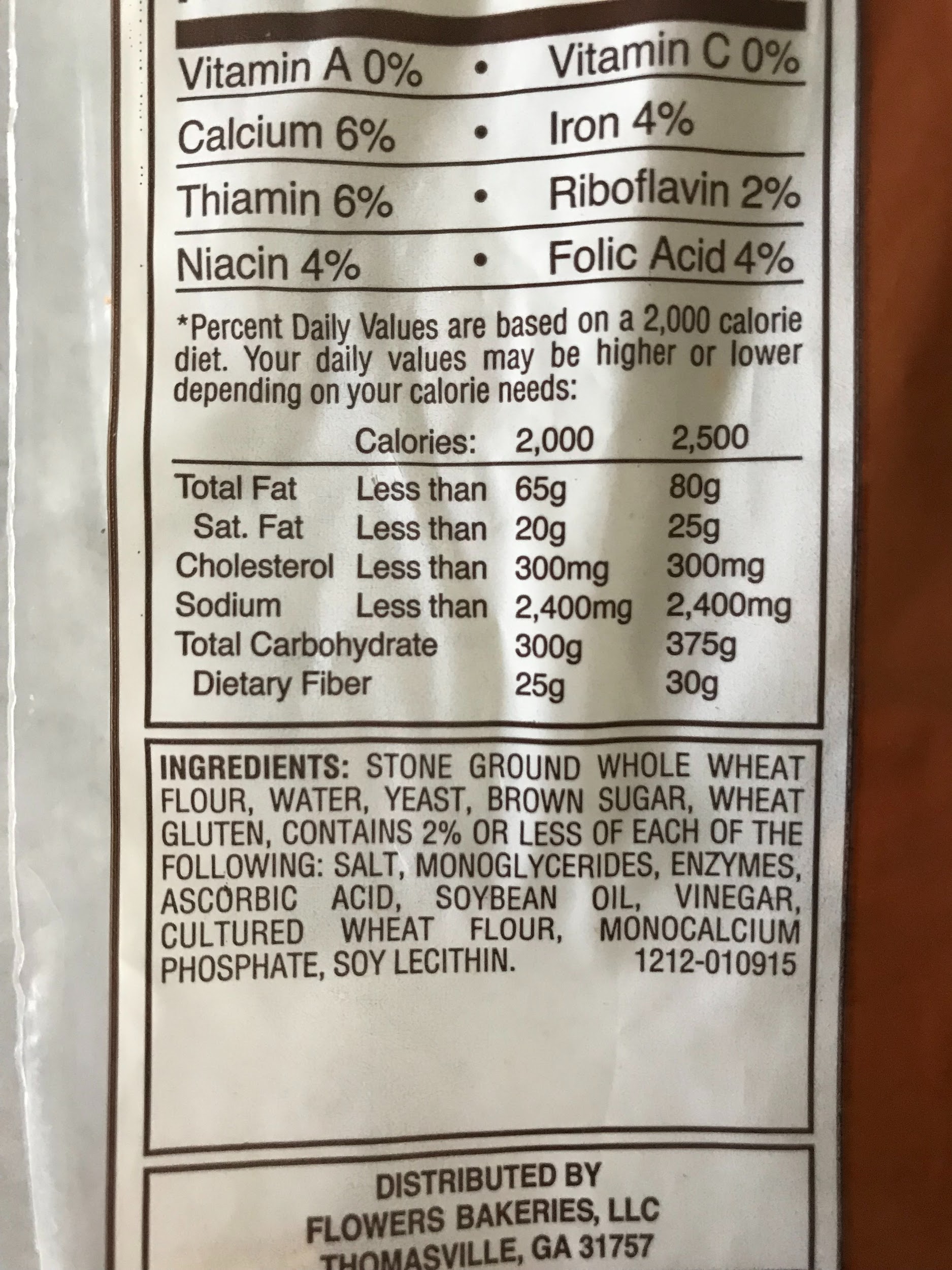

To determine if a product is a good source of whole grain, the best place to look is the ingredient list on the Nutrition Facts panel. The ingredients should list a whole grain as the first ingredient (e.g., 100% whole wheat), and it should not be followed by a bunch of refined grains such as enriched wheat flour.

Getting familiar with the name of whole grains will help you identify them. Common varieties include wheat, barley, brown rice, buckwheat, corn, rye, oats, and wild rice. Less known varieties include teff, amaranth, millet, quinoa, black rice, black barley, and spelt.

Most, but not all, whole grains are a good source of fiber, and that is one of the benefits of choosing whole grains. Keep in mind that some products add extra fiber as a separate ingredient, like wheat bran, inulin, or cellulose. These boost the grams of fiber on the Nutrition Facts label and may make the product a good source of fiber, but it doesn’t mean it’s a good source of whole grains. In fact, it may be a product made mostly of refined grains, so it would still be missing the other nutrients that come packaged in whole grains and may not have the same health benefits. Therefore, just looking at fiber on the Nutrition Facts label is not a good indicator of whether or not the product is made with whole grains.

Also, some products that are 100% whole wheat but do not appear to be a good source of fiber, because the serving size is small. The bread label below is an example of this. The first ingredient is “stone ground whole wheat flour” with no refined flours listed, but it still has only 2g of fiber and 9% DV. But of course, that still contributes to your fiber intake for the day, and if you made yourself a sandwich with two slices of bread, that would provide 18% of the DV.

Figure 4.28. Example of 100% whole wheat bread with Nutrition Facts and ingredient list.

VIDEO: “Label Reading and Whole Grains” by Tamberly Powell, YouTube (September 24, 2018), 7:46 minutes.

Self-Check:

References:

- Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. (2005). Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/10490/chapter/1

- U.S Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory. (2014). USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 27. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. (2015). Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health Implications of Dietary Fiber. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 115(11), 1861–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.003

- Whole Grain Council. Definition of a Whole Grain. Retrieved from https://wholegrainscouncil.org/definition-whole-grain

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2018). Dietary Fiber: Essential for a healthy diet. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/fiber/art-20043983

Image Credits:

- Figure 4.22. “Chemical structure of cellulose” by laghi.l is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

- Figure 4.23. “Bowl of oatmeal” by Rusvaplauke is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Table 4.4. “Common foods listed with standard portion size, and calories and fiber in a standard portion” by Tamberly Powell is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 ; values in table from USDA National Nutrient Database are in the Public Domain

- Figure 4.24. “Grain” by rethought is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

- Figure 4.25. “Wheat kernel” by Phuthinh Co is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

- Figure 4.26. “Chart comparing nutrient content of whole wheat flour, refined flour and enriched wheat flour” permission for use was given by “Oldways Whole Grains Council”

- Figure 4.27. “Whole grain intake graphic” by Dietary Guidelines for Americans, Figure 2-5 is in the Public Domain

- Figure 4.28. “100% whole wheat bread and label photos” by Tamberly Powell is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Non-digestible carbohydrates that are found in plants.

One of the most common types of fiber; the main component in plant cell walls.

A type of fiber that dissolves in water and helps to decrease blood glucose spikes and lower blood cholesterol levels; pectins and gums are common types of soluble fibers, and good food sources include oat bran, barley, nuts, seeds, beans, lentils, peas, and some fruits and vegetables.

A type of fiber that does not typically dissolve in water and helps prevent constipation; lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose are common types of insoluble fibers, and food sources include wheat bran, vegetables, fruits, and whole grains.

The outer skin of a wheat kernel; contains antioxidants, B vitamins, and fiber.

The largest part of the wheat kernel; provides energy in the form of starch to support reproduction.

The embryo of the seed, which can sprout into a new plant; contains B vitamins, protein, minerals, and healthy fats.

Grains and grain products made from the entire grain seed, including the bran, germ, and endosperm.

Grains and grain products made only from the endosperm.

Food ingredients with added nutrients; usually refined grains that have lost naturally-occurring nutrients during processing.