22 15. Bivariate analysis

Matthew DeCarlo

Chapter Outline

- What is bivariate data analysis? (5 minute read)

- Chi-square (4 minute read)

- Correlations (5 minute read)

- T-tests (5 minute read)

- ANOVA (6 minute read)

Content warning: examples in this chapter include discussions of anxiety symptoms.

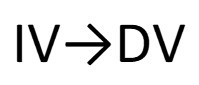

So now we get to the math! Just kidding. Mostly. In this chapter, you are going to learn more about bivariate analysis, or analyzing the relationship between two variables. I don’t expect you to finish this chapter and be able to execute everything you just read about—instead, the big goal here is for you to be able to understand what bivariate analysis is, what kinds of analyses are available, and how you can use them in your research.

Take a deep breath, and let’s look at some numbers!

15.1 What is bivariate analysis?

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define bivariate analysis

- Explain when we might use bivariate analysis in social work research

Did you know that ice cream causes shark attacks? It’s true! When ice cream sales go up in the summer, so does the rate of shark attacks. So you’d better put down that ice cream cone, unless you want to make yourself look more delicious to a shark.

Ok, so it’s quite obviously not true that ice cream causes shark attacks. But if you looked at these two variables and how they’re related, you’d notice that during times of the year with high ice cream sales, there are also the most shark attacks. Despite the fact that the conclusion we drew about the relationship was wrong, it’s nonetheless true that these two variables appear related, and researchers figured that out through the use of bivariate analysis. (For a refresher on correlation versus causation, head back to Chapter 8.)

Bivariate analysis consists of a group of statistical techniques that examine the relationship between two variables. We could look at how anti-depressant medications and appetite are related, whether there is a relationship between having a pet and emotional well-being, or if a policy-maker’s level of education is related to how they vote on bills related to environmental issues.

Bivariate analysis forms the foundation of multivariate analysis, which we don’t get to in this book. All you really need to know here is that there are steps beyond bivariate analysis, which you’ve undoubtedly seen in scholarly literature already! But before we can move forward with multivariate analysis, we need to understand whether there are any relationships between our variables that are worth testing.

A study from Kwate, Loh, White, and Saldana (2012) illustrates this point. These researchers were interested in whether the lack of retail stores in predominantly Black neighborhoods in New York City could be attributed to the racial differences of those neighborhoods. Their hypothesis was that race had a significant effect on the presence of retail stores in a neighborhood, and that Black neighborhoods experience “retail redlining”—when a retailer decides not to put a store somewhere because the area is predominantly Black.

The researchers needed to know if the predominant race of a neighborhood’s residents was even related to the number of retail stores. With bivariate analysis, they found that “predominantly Black areas faced greater distances to retail outlets; percent Black was positively associated with distance to nearest store for 65 % (13 out of 20) stores” (p. 640). With this information in hand, the researchers moved on to multivariate analysis to complete their research.

Statistical significance

Before we dive into analyses, let’s talk about statistical significance. Statistical significance is the extent to which our statistical analysis has produced a result that is likely to represent a real relationship instead of some random occurrence. But just because a relationship isn’t random doesn’t mean it’s useful for drawing a sound conclusion.

We went into detail about statistical significance in Chapter 5. You’ll hopefully remember that there, we laid out some key principles from the American Statistical Association for understanding and using p-values in social science:

- P-values can indicate how incompatible the data are with a specified statistical model. P-values can provide evidence against the null hypothesis or the underlying assumptions of the statistical model the researchers used.

- P-values do not measure the probability that the studied hypothesis is true, or the probability that the data were produced by random chance alone. Both are inaccurate, though common, misconceptions about statistical significance.

- Scientific conclusions and business or policy decisions should not be based only on whether a p-value passes a specific threshold. More nuance is needed to interpret scientific findings, as a conclusion does not become true or false when it passes from p=0.051 to p=0.049.

- Proper inference requires full reporting and transparency, rather than cherry-picking promising findings or conducting multiple analyses and only reporting those with significant findings. For the authors of this textbook, we believe the best response to this issue is for researchers make their data openly available to reviewers and general public and register their hypotheses in a public database prior to conducting analyses.

- A p-value, or statistical significance, does not measure the size of an effect or the importance of a result. In our culture, to call something significant is to say it is larger or more important, but any effect, no matter how tiny, can produce a small p-value if the study is rigorous enough. Statistical significance is not equivalent to scientific, human, or economic significance.

- By itself, a p-value does not provide a good measure of evidence regarding a model or hypothesis. For example, a p-value near 0.05 taken by itself offers only weak evidence against the null hypothesis. Likewise, a relatively large p-value does not imply evidence in favor of the null hypothesis; many other hypotheses may be equally or more consistent with the observed data. (adapted from Wasserstein & Lazar, 2016, p. 131-132).[1]

A statistically significant result is not necessarily a strong one. Even a very weak result can be statistically significant if it is based on a large enough sample. The word significant can cause people to interpret these differences as strong and important, to the extent that they might even affect someone’s behavior. As we have seen however, these statistically significant differences are actually quite weak—perhaps even “trivial.” The correlation between ice cream sales and shark attacks is statistically significant, but practically speaking, it’s meaningless.

There is debate about acceptable p-values in some disciplines. In medical sciences, a p-value even smaller than 0.05 is often favored, given the stakes of biomedical research. Some researchers in social sciences and economics argue that a higher p-value of up to 0.10 still constitutes strong evidence. Other researchers think that p-values are entirely overemphasized and that there are better measures of statistical significance. At this point in your research career, it’s probably best to stick with 0.05 because you’re learning a lot at once, but it’s important to know that there is some debate about p-values and that you shouldn’t automatically discount relationships with a p-value of 0.06.

A note about “assumptions”

For certain types of bivariate, and in general for multivariate, analysis, we assume a few things about our data and the way it’s distributed. The characteristics we assume about our data that makes it suitable for certain types of statistical tests are called assumptions. For instance, we assume that our data has a normal distribution. While I’m not going to go into detail about these assumptions because it’s beyond the scope of the book, I want to point out that it is important to check these assumptions before your analysis.

Something else that’s important to note is that going through this chapter, the data analyses presented are merely for illustrative purposes—the necessary assumptions have not been checked. So don’t draw any conclusions based on the results shared.

For this chapter, I’m going to use a data set from IPUMS USA, where you can get individual-level, de-identified U.S. Census and American Community Survey data. The data are clean and the data sets are large, so it can be a good place to get data you can use for practice.

Key Takeaways

- Bivariate analysis is a group of statistical techniques that examine the relationship between two variables.

- You need to conduct bivariate analyses before you can begin to draw conclusions from your data, including in future multivariate analyses.

- Statistical significance and p-values help us understand the extent to which the relationships we see in our analyses are real relationships, and not just random or spurious.

Exercises

- Find a study from your literature review that uses quantitative analyses. What kind of bivariate analyses did the authors use? You don’t have to understand everything about these analyses yet!

- What do the p-values of their analyses tell you?

15.2 Chi-square

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain the uses of Chi-square test for independence

- Explain what kind of variables are appropriate for a Chi-square test

- Interpret results of a Chi-square test and draw a conclusion about a hypothesis from the results

The first test we’re going to introduce you to is known as a Chi-square test (sometimes denoted as χ2) and is foundational to analyzing relationships between nominal or ordinal variables. A Chi-square test for independence (Chi-square for short) is a statistical test to determine whether there is a significant relationship between two nominal or ordinal variables. The “test for independence” refers to the null hypothesis of our comparison—that the two variables are independent and have no relationship.

A Chi-square can only be used for the relationship between two nominal or ordinal variables—there are other tests for relationships between other types of variables that we’ll talk about later in this chapter. For instance, you could use a Chi-square to determine whether there is a significant relationship between a person’s self-reported race and whether they have health insurance through their employer. (We will actually take a look at this a little later.)

Chi-square tests the hypothesis that there is a relationship between two categorical variables by comparing the values we actually observed and the value we would expect to occur based on our null hypothesis. The expected value is a calculation based on your data when it’s in a summarized form called a contingency table, which is a visual representation of a cross-tabulation of categorical variables to demonstrate all the possible occurrences of your categories. I know that sounds complex, so let’s look at an example.

Earlier, we talked about looking at the relationship between a person’s race and whether they have health insurance through an employer. Based on 2017 American Community Survey data from IPUMS, this is what a contingency table for these two variables would look like.

| Race | No insurance through employer/union | Has insurance through employer/union | Total |

| White | 1,037,071 | 1,401,453 | 2,438,524 |

| Black/African American | 177,648 | 177,648 | 317,308 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 24,123 | 12,142 | 36,265 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 71,155 | 105,596 | 176,751 |

| Another race | 75,117 | 46,699 | 121,816 |

| Two or more major races | 46,107 | 53,269 | 87,384 |

| Total | 1,431,221 | 1,758,819 | 3,190,040 |

So now we know what our observed values for these categories are. Next, let’s think about our expected values. We don’t need to get so far into it as to put actual numbers to it, but we can come up with a hypothesis based on some common knowledge about racial differences in employment. (We’re going to be making some generalizations here, so remember that there can be exceptions.)

An applied example

Let’s say research shows that people who identify as black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) tend to hold multiple part-time jobs and have a higher unemployment rate in general. Given that, our hypothesis based on this data could be that BIPOC people are less likely to have employer-provided health insurance. Before we can assess a likelihood, we need to know if these to variables are even significantly related. Here’s where our Chi-square test comes in!

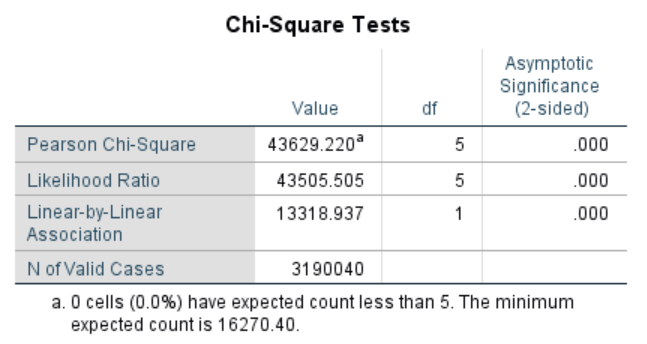

I’ve used SPSS to run these tests, so depending on what statistical program you use, your outputs might look a little different.

There are a number of different statistics reported here. What I want you to focus on is the first line, the Pearson Chi-Square, which is the most commonly used statistic for larger samples that have more than two categories each. (The other two lines are alternatives to Pearson that SPSS puts out automatically, but they are appropriate for data that is different from ours, so you can ignore them. You can also ignore the “df” column for now, as it’s a little advanced for what’s in this chapter.)

The last column gives us our statistical significance level, which in this case is 0.00. So what conclusion can we draw here? The significant Chi-square statistic means we can reject the null hypothesis (which is that our two variables are not related). There is likely a strong relationship between our two variables that is probably not random, meaning that we should further explore the relationship between a person’s race and whether they have employer-provided health insurance. Are there other factors that affect the relationship between these two variables? That seems likely. (One thing to keep in mind is that this is a large data set, which can inflate statistical significance levels. However, for the purposes of our exercises, we’ll ignore that for now.)

What we cannot conclude is that these two variables are causally related. That is, someone’s race doesn’t cause them to have employer-provided health insurance or not. It just appears to be a contributing factor, but we are not accounting for the effect of other variables on the relationship we observe (yet).

Key Takeaways

- The Chi-square test is designed to test the null hypothesis that our two variables are not related to each other.

- The Chi-square test is only appropriate for nominal and/or ordinal variables.

- A statistically significant Chi-square statistic means we can reject the null hypothesis and assume our two variables are, in fact, related.

- A Chi-square test doesn’t let us draw any conclusions about causality because it does not account for the influence of other variables on the relationship we observe.

Exercises

Think about the data you could collect or have collected for your research project. If you were to conduct a chi-square test, consider:

- Which two variables would you most like to use in the analysis?

- What about the relationship between these two variables interests you in light of what your literature review has shown so far?

15.3 Correlations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define correlation and understand how to use it in quantitative analysis

- Explain what kind of variables are appropriate for a correlation

- Interpret a correlation coefficient

- Define the different types of correlation—positive and negative

- Interpret results of a correlation and draw a conclusion about a hypothesis from the results

A correlation is a relationship between two variables in which their values change together. For instance, we might expect education and income to be correlated—as a person’s educational attainment (how much schooling they have completed) goes up, so does their income. What about minutes of exercise each week and blood pressure? We would probably expect those who exercise more have lower blood pressures than those who don’t. We can test these relationships using correlation analyses. Correlations are appropriate only for two interval/ratio variables.

It’s very important to understand that correlations can tell you about relationships, but not causes—as you’ve probably already heard, correlation is not causation! Go back to our example about shark attacks and ice cream sales from the beginning of the chapter. Clearly, ice cream sales don’t cause shark attacks, but the two are strongly correlated (most likely because both increase in the summer for other reasons). This relationship is an example of a spurious relationship, or a relationship that appears to exist between to variables, but in fact does not and is caused by other factors. We hear about these all the time in the news and correlation analyses are often misrepresented. As we talked about in Chapter 4 when discussing critical information literacy, your job as a researcher and informed social worker is to make sure people aren’t misstating what these analyses actually mean, especially when they are being used to harm vulnerable populations.

An applied example

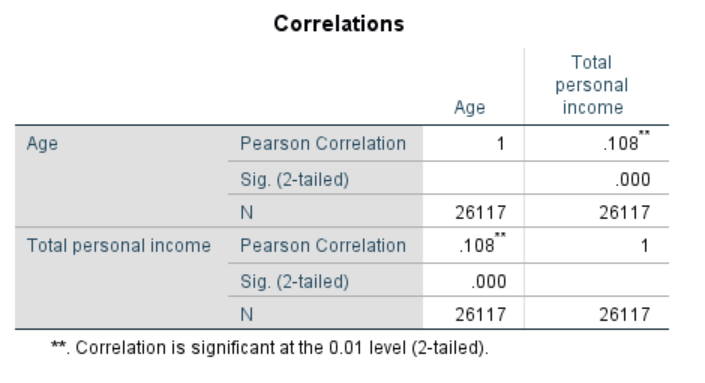

Let’s say we’re looking at the relationship between age and income among indigenous people in the United States. In the data set we’ve been using so far, these folks generally fall into the racial category of American Indian/Alaska native, so we’ll use that category because it’s the best we can do. Using SPSS, this is the output you’d get with these two variables for this group. We’ll also limit the analysis to people age 18 and over since children are unlikely to report an individual income.

Here’s Pearson again, but don’t be confused—this is not the same test as the Chi-square, it just happens to be named after the same person. First, let’s talk about the number next to Pearson Correlation, which is the correlation coefficient. The correlation coefficient is a statistically derived value between -1 and 1 that tells us the magnitude and direction of the relationship between two variables. A statistically significant correlation coefficient like the one in this table (denoted by a p-value of 0.01) means the relationship is not random.

The magnitude of the relationship is how strong the relationship is and can be determined by the absolute value of the coefficient. In the case of our analysis in the table above, the correlation coefficient is 0.108, which denotes a pretty weak relationship. This means that, among the population in our sample, age and income don’t have much of an effect on each other. (If the correlation coefficient were -0.108, the conclusion about its strength would be the same.)

In general, you can say that a correlation coefficient with an absolute value below 0.5 represents a weak correlation. Between 0.5 and 0.75 represents a moderate correlation, and above 0.75 represents a strong correlation. Although the relationship between age and income in our population is statistically significant, it’s also very weak.

The sign on your correlation coefficient tells you the direction of your relationship. A positive correlation or direct relationship occurs when two variables move together in the same direction—as one increases, so does the other, or, as one decreases, so does the other. Correlation coefficients will be positive, so that means the correlation we calculated is a positive correlation and the two variables have a direct, though very weak, relationship. For instance, in our example about shark attacks and ice cream, the number of both shark attacks and pints of ice cream sold would go up, meaning there is a direct relationship between the two.

A negative correlation or inverse relationship occurs when two variables change in opposite directions—one goes up, the other goes down and vice versa. The correlation coefficient will be negative. For example, if you were studying social media use and found that time spent on social media corresponded to lower scores on self-esteem scales, this would represent an inverse relationship.

Correlations are important to run at the outset of your analyses so you can start thinking about how variables relate to each other and whether you might want to include them in future multivariate analyses. For instance, if you’re trying to understand the relationship between receipt of an intervention and a particular outcome, you might want to test whether client characteristics like race or gender are correlated with your outcome; if they are, they should be plugged into subsequent multivariate models. If not, you might want to consider whether to include them in multivariate models.

A final note

Just because the correlation between your dependent variable and your primary independent variable is weak or not statistically significant doesn’t mean you should stop your work. For one thing, disproving your hypothesis is important for knowledge-building. For another, the relationship can change when you consider other variables in multivariate analysis, as they could mediate or moderate the relationships.

Key Takeaways

- Correlations are a basic measure of the strength of the relationship between two interval/ratio variables.

- A correlation between two variables does not mean one variable causes the other one to change. Drawing conclusions about causality from a simple correlation is likely to lead to you to describing a spurious relationship, or one that exists at face value, but doesn’t hold up when more factors are considered.

- Correlations are a useful starting point for almost all data analysis projects.

- The magnitude of a correlation describes its strength and is indicated by the correlation coefficient, which can range from -1 to 1.

- A positive correlation, or direct relationship, occurs when the values of two variables move together in the same direction.

- A negative correlation, or inverse relationship, occurs when the value of one variable moves one direction, while the value of the other variable moves the opposite direction.

Exercises

Think about the data you could collect or have collected for your research project. If you were to conduct a correlation analysis, consider:

- Which two variables would you most like to use in the analysis?

- What about the relationship between these two variables interests you in light of what your literature review has shown so far?

15.4 T-tests

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe the three different types of t-tests and when to use them.

- Explain what kind of variables are appropriate for t-tests.

At a very basic level, t-tests compare the means between two groups, the same group at two points in time, or a group and a hypothetical mean. By doing so using this set of statistical analyses, you can learn whether these differences are reflective of a real relationship or not (whether they are statistically significant).

Say you’ve got a data set that includes information about marital status and personal income (which we do!). You want to know if married people have higher personal (not family) incomes than non-married people, and whether the difference is statistically significant. Essentially, you want to see if the difference in average income between these two groups is down to chance or if it warrants further exploration. What analysis would you run to find this information? A t-test!

A lot of social work research focuses on the effect of interventions and programs, so t-tests can be particularly useful. Say you were studying the effect of a smoking cessation hotline on the number of days participants went without smoking a cigarette. You might want to compare the effect for men and women, in which case you’d use an independent samples t-test. If you wanted to compare the effect of your smoking cessation hotline to others in the country and knew the results of those, you would use a one-sample t-test. And if you wanted to compare the average number of cigarettes per day for your participants before they started a tobacco education group and then again when they finished, you’d use a paired-samples t-test. Don’t worry—we’re going into each of these in detail below.

So why are they called t-tests? Basically, when you conduct a t-test, you’re comparing your data to a theoretical distribution of data known as the t distribution to get the t statistic. The t distribution is normal, so when your data are not normally distributed, a t distribution can approximate a normal distribution well enough for you to test some hypotheses. (Remember our discussion of assumptions in section 15.1—one of them is that data be normally distributed.) Ultimately, the t statistic that the test produces allows you to determine if any differences are statistically significant.

For t-tests, you need to have an interval/ratio dependent variable and a nominal or ordinal independent variable. Basically, you need an average (using an interval or ratio variable) to compare across mutually exclusive groups (using a nominal or ordinal variable).

Let’s jump into the three different types of t-tests.

Paired samples t-test

The paired samples t-test is used to compare two means for the same sample tested at two different times or under two different conditions. This comparison is appropriate for pretest-post-test designs or within-subjects experiments. The null hypothesis is that the means at the two times or under the two conditions are the same in the population. The alternative hypothesis is that they are not the same.

For example, say you are testing the effect of pet ownership on anxiety symptoms. You have access to a group of people who have the same diagnosis involving anxiety who do not have pets, and you give them a standardized anxiety inventory questionnaire. Then, each of these participants gets some kind of pet and after 6 months, you give them the same standardized anxiety questionnaire.

To compare their scores on the questionnaire at the beginning of the study and after 6 months of pet ownership, you would use paired samples t-test. Since the sample includes the same people, the samples are “paired” (hence the name of the test). If the t-statistic is statistically significant, there is evidence that owning a pet has an effect on scores on your anxiety questionnaire.

Independent samples/two samples t-test

An independent/two samples t-test is used to compare the means of two separate samples. The two samples might have been tested under different conditions in a between-subjects experiment, or they could be pre-existing groups in a cross-sectional design (e.g., women and men, extroverts and introverts). The null hypothesis is that the means of the two populations are the same. The alternative hypothesis is that they are not the same.

Let’s go back to our example related to anxiety diagnoses and pet ownership. Say you want to know if people who own pets have different scores on certain elements of your standard anxiety questionnaire than people who don’t own pets.

You have access to two groups of participants: pet owners and non-pet owners. These groups both fit your other study criteria. You give both groups the same questionnaire at one point in time. You are interested in two questions, one about self-worth and one about feelings of loneliness. You can calculate mean scores for the questions you’re interested in and then compare them across two groups. If the t-statistic is statistically significant, then there is evidence of a difference in these scores that may be due to pet ownership.

One-sample t-test

Finally, let’s talk about a one sample t-test. This t-test is appropriate when there is an external benchmark to use for your comparison mean, either known or hypothesized. The null hypothesis for this kind of test is that the mean in your sample is different from the mean of the population. The alternative hypothesis is that the means are different.

Let’s say you know the average years of post-high school education for Black women, and you’re interested in learning whether the Black women in your study are on par with the average. You could use a one-sample t-test to determine how your sample’s average years of post-high school education compares to the known value in the population. This kind of t-test is useful when a phenomenon or intervention has already been studied, or to see how your sample compares to your larger population.

Key Takeaways

- There are three types of t-tests that are each appropriate for different situations. T-tests can only be used with an interval/ratio dependent variable and a nominal/ordinal independent variable.

- T-tests in general compare the means of one variable between either two points in time or conditions for one group, two different groups, or one group to an external benchmark variable..

- In a paired-samples t-test, you are comparing the means of one variable in your data for the same group, either at two different times or under two different conditions, and testing whether the difference is statistically significant.

- In an independent samples t-test, you are comparing the means of one variable in your data for two different groups to determine if any difference is statistically significant.

- In a one-sample t-test, you are comparing the mean of one variable in your data to an external benchmark, either observed or hypothetical.

Exercises

Think about the data you could collect or have collected for your research project. If you were to conduct a t-test, consider:

- Which t-test makes the most sense for your data and research design? Why?

- Which variable would be an appropriate dependent variable? Why?

- Which variable would be an interesting independent variable? Why?

15.5 ANOVA (ANalysis Of VAriance)

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain what kind of variables are appropriate for ANOVA

- Explain the difference between one-way and two-way ANOVA

- Come up with an example of when each type of ANOVA is appropriate

Analysis of variance, generally abbreviated to ANOVA for short, is a statistical method to examine how a dependent variable changes as the value of a categorical independent variable changes. It serves the same purpose as the t-tests we learned in 15.4: it tests for differences in group means. ANOVA is more flexible in that it can handle any number of groups, unlike t-tests, which are limited to two groups (independent samples) or two time points (dependent samples). Thus, the purpose and interpretation of ANOVA will be the same as it was for t-tests.

There are two types of ANOVA: a one-way ANOVA and a two-way ANOVA. One-way ANOVAs are far more common than two-way ANOVAs.

One-way ANOVA

The most common type of ANOVA that researchers use is the one-way ANOVA, which is a statistical procedure to compare the means of a variable across three or more groups of an independent variable. Let’s take a look at some data about income of different racial and ethnic groups in the United States. The data in Table 15.2 below comes from the US Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey[2]. The racial and ethnic designations in the table reflect what’s reported by the Census Bureau, which is not fully representative of how people identify racially.

| Race | Average income |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | $20,709 |

| Asian | $40,878 |

| Black/African American | $23,303 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | $25,304 |

| White | $36,962 |

| Two or more races | $19,162 |

| Another race | $20,482 |

Off the bat, of course, we can see a difference in the average income between these groups. Now, we want to know if the difference between average income of these racial and ethnic groups is statistically significant, which is the perfect situation to use one-way ANOVA. To conduct this analysis, we need the person-level data that underlies this table, which I was able to download from IPUMS. For this analysis, race is the independent variable (nominal) and total income is the dependent variable (interval/ratio). Let’s assume for this exercise that we have no other data about the people in our data set besides their race and income. (If we did, we’d probably do another type of analysis.)

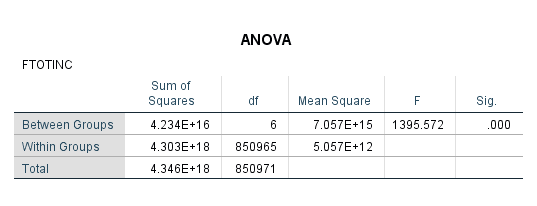

I used SPSS to run a one-way ANOVA using this data. With the basic analysis, the first table in the output was the following.

Without going deep into the statistics, the column labeled “F” represents our F statistic, which is similar to the T statistic in a t-test in that it gives a statistical point of comparison for our analysis. The important thing to noticed here, however, is our significance level, which is .000. Sounds great! But we actually get very little information here—all we know is that the between-group differences are statistically significant as a whole, but not anything about the individual groups.

This is where post hoc tests come into the picture. Because we are comparing each race to each other race, that adds up to a lot of comparisons, and statistically, this increases the likelihood of a type I error. A post hoc test in ANOVA is a way to correct and reduce this error after the fact (hence “post hoc”). I’m only going to talk about one type—the Bonferroni correction—because it’s commonly used. However, there are other types of post hoc tests you may encounter.

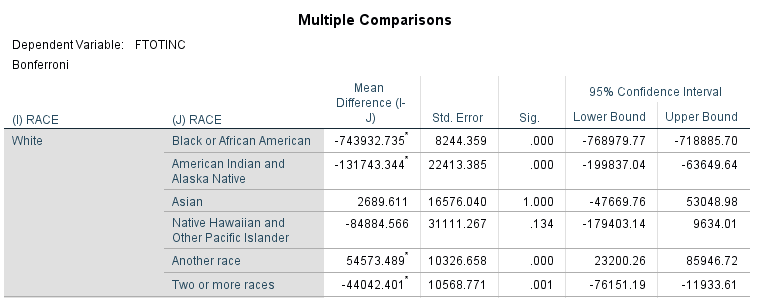

When I tell SPSS to run the ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction, in addition to the table above, I get a very large table that runs through every single comparison I asked it to make among the groups in my independent variable—in this case, the different races. Figure 15.4 below is the first grouping in that table—they will all give the same conceptual information, though some of the signs on the mean difference and, consequently the confidence intervals, will vary.

Now we see some points of interest. As you’d expect knowing what we know from prior research, race seems to have a pretty strong influence on a person’s income. (Notice I didn’t say “effect”—we don’t have enough information to establish causality!) The significance levels for the mean of White people’s incomes compared to the mean of several races are .000. Interestingly, for Asian people in the US, race appears to have no influence on their income compared to White people in the US. The significance level for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders is also relatively high.

So what does this mean? We can say with some confidence that, overall, race seems to influence a person’s income. In our hypothetical data set, since we only have race and income, this is a great analysis to conduct. But do we think that’s the only thing that influences a person’s income? Probably not. To look at other factors if we have them, we can use a two-way ANOVA.

Two-way ANOVA and n-way ANOVA

A two-way ANOVA is a statistical procedure to compare the means of a variable across groups using multiple independent variables to distinguish among groups. For instance, we might want to examine income by both race and gender, in which case, we would use a two-way ANOVA. Fundamentally, the procedures and outputs for two-way ANOVA are almost identical to one-way ANOVA, just with more cross-group comparisons, so I am not going to run through an example in SPSS for you.

You may also see textbooks or scholarly articles refer to n-way ANOVAs. Essentially, just like you’ve seen throughout this book, the n can equal just about any number. However, going far beyond a two-way ANOVA increases your likelihood of a type I error, for the reasons discussed in the previous section.

A final note

You may notice that this book doesn’t get into multivariate analysis at all. Regression analysis, which you’ve no doubt seen in many academic articles you’ve read, is an incredibly complex topic. There are entire courses and textbooks on the multiple different types of regression analysis, and we did not think we could adequately cover regression analysis at this level. Don’t let that scare you away from learning about it—just understand that we don’t expect you to know about it at this point in your research learning.

Key Takeaways

- One-way ANOVA is a statistical procedure to compare the means of a variable across three or more categories of an independent variable. This analysis can help you understand whether there are meaningful differences in your sample based on different categories like race, geography, gender, or many others.

- Two-way ANOVA is almost identical to one-way ANOVA, except that you can compare the means of a variable across multiple independent variables.

Exercises

Think about the data you could collect or have collected for your research project. If you were to conduct a one-way ANOVA, consider:

- Which variable would be an appropriate dependent variable? Why?

- Which variable would be an interesting independent variable? Why?

- Would you want to conduct a two-way or n-way ANOVA? If so, what other independent variables would you use, and why?

- Wasserstein, R. L., & Lazar, N. A. (2016). The ASA statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. The American Statistician, 70, p. 129-133. ↵

- Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, Erin Meyer, Jose Pacas and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 10.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V10.0 ↵

A type of reliability in which multiple forms of a tool yield the same results from the same participants.

The extent to which scores obtained on a scale or other measure are consistent across time

Context is the circumstances surrounding an artifact, event, or experience.

variables whose values are mutually exclusive and can be used in mathematical operations

Variables with finite value choices.

“a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences and the settings in which research findings are to be received and, where appropriate, communicating and interacting with wider policy and…service audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake in decision-making processes and practice” (Wilson, Petticrew, Calnan, & Natareth, 2010, p. 91)

the tendency for a pattern to occur at regular intervals

the process by which the researcher informs potential participants about the study and attempts to get them to participate

In nonequivalent comparison group designs, the process in which researchers match the population profile of the comparison and experimental groups.

In nonequivalent comparison group designs, the process by which researchers match individual cases in the experimental group to similar cases in the comparison group.

The bias that occurs when those who respond to your request to participate in a study are different from those who do not respond to you request to participate in a study.

Chapter outline

- 15.1 Alternative paradigms: Interpretivism, critical paradigm, and pragmatism

- 15.2 Multiparadigmatic research: An example

- 15.3 Idiographic causal relationships

- 15.4 Qualitative research questions

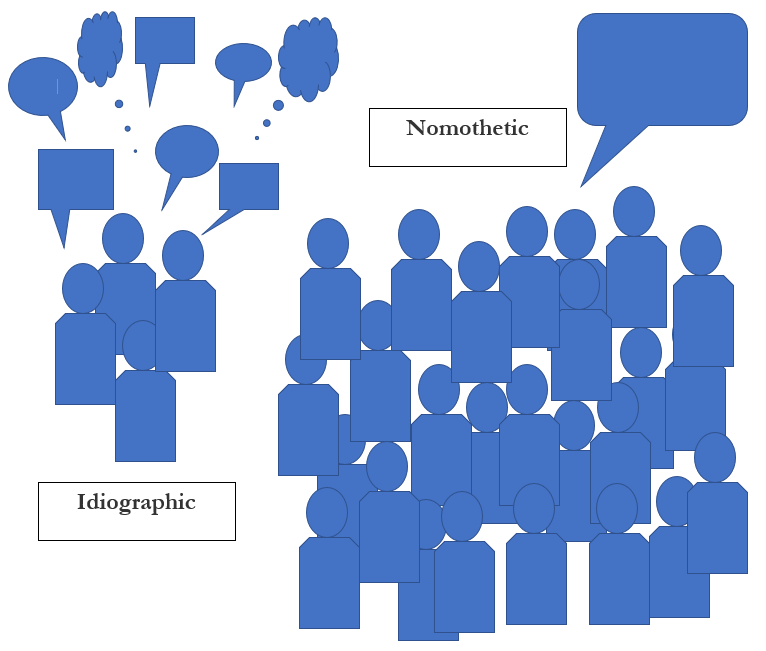

Now let's change things up! In the previous chapters, we explored steps to create and carry out a quantitative research study. Quantitative studies are great when we want to summarize or test relationships between ideas using numbers and the power of statistics. However, qualitative research offers us a different and equally important tool. Sometimes the aim of research projects is to explore meaning and lived experience. Instead of trying to arrive at generalizable conclusions for all people, some research projects establish a deep, authentic description of a specific time, place, and group of people.

Qualitative research relies on the power of human expression through words, pictures, movies, performance and other artifacts that represent these things. All of these tell stories about the human experience and we want to learn from them and have them be represented in our research. Generally speaking, qualitative research is about the gathering up of these stories, breaking them into pieces so we can examine the ideas that make them up, and putting them back together in a way that allows us to tell a common or shared story that responds to our research question. To do that, we need to discuss the assumptions underlying social science.

17.1 Alternative paradigms: Interpretivism, critical, and pragmatism

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to...

- Distinguish between the assumptions of positivism, interpretivism, critical, and pragmatist research paradigms.

- Use paradigm to describe how scientific thought changes over time.

In Chapter 10, we reviewed the assumptions that underly post-positivism (abbreviated hereafter as positivism for brevity). Quantitative methods are most often the choice for positivist research questions because they conform to these assumptions. Qualitative methods can conform to these assumptions; however, they are limited in their generalizability.

Kivunja & Kuyini (2017)[1] describe the essential features of positivism as:

- A belief that theory is universal and law-like generalizations can be made across contexts

- The assumption that context is not important

- The belief that truth or knowledge is ‘out there to be discovered’ by research

- The belief that cause and effect are distinguishable and analytically separable

- The belief that results of inquiry can be quantified

- The belief that theory can be used to predict and to control outcomes

- The belief that research should follow the scientific method of investigation

- Rests on formulation and testing of hypotheses

- Employs empirical or analytical approaches

- Pursues an objective search for facts

- Believes in ability to observe knowledge

- The researcher’s ultimate aim is to establish a comprehensive universal theory, to account for human and social behavior

- Application of the scientific method

Because positivism is the dominant social science research paradigm, it can be easy to ignore or be confused by research that does not use these assumptions. We covered in Chapter 10 the table reprinted below when discussing the assumptions underlying positivistic social science.

As you consider your research project, keep these philosophical assumptions in mind. They are useful shortcuts to understanding the deeper ideas and assumptions behind the construction of knowledge. The purpose of exploring these philosophical assumptions isn't to find out which is true and which is false. Instead, the goal is to identify the assumptions that fit with how you think about your research question. Choosing a paradigm helps you make those assumptions explicit.

| Assumptions | Central conflicts |

| Ontology: assumptions about what is real | Realism vs. anti-realism (a.k.a. relativism) |

| Epistemology: assumptions about how we come to know what is real | Objective truth vs. subjective truths

Math vs. language/expression Prediction vs. understanding |

| Assumptions about the researcher | Researcher as unbiased vs. researcher shaped by oppression, culture, and history

Researcher as neutral force vs. researcher as oppressive force |

| Assumptions about human action | Determinism vs. free will

Holism vs. individualism |

| Assumptions about the social world | Orderly and consensus-focused vs. disorderly and conflict-focused |

| Assumptions about the purpose of research | Study the status quo vs. create radical change

Values-neutral vs. values-informed |

Before we explore alternative paradigms, it's important for us to review what paradigms are.

How do scientific ideas change over time?

Much like your ideas develop over time as you learn more, so does the body of scientific knowledge. Kuhn’s (1962)[2] The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is one of the most influential works on the philosophy of science, and is credited with introducing the idea of competing paradigms (or “disciplinary matrices”) in research. Kuhn investigated the way that scientific practices evolve over time, arguing that we don’t have a simple progression from “less knowledge” to “more knowledge” because the way that we approach inquiry is changing over time. This can happen gradually, but the process results in moments of change where our understanding of a phenomenon changes more radically (such as in the transition from Newtonian to Einsteinian physics; or from Lamarckian to Darwinian theories of evolution). For a social work practice example, Fleuridas & Krafcik (2019)[3] trace the development of the "four forces" of psychotherapy, from psychodynamics to behaviorism to humanism as well as the competition among emerging perspectives to establish itself as the fourth force to guide psychotherapeutic practice. But how did the problems in one paradigm inspire new paradigms? Kuhn presents us with a way of understanding the history of scientific development across all topics and disciplines.

As you can see in this video from Matthew J. Brown (CC-BY), there are four stages in the cycle of science in Kuhn’s approach. Firstly, a pre-paradigmatic state where competing approaches share no consensus. Secondly, the “normal” state where there is wide acceptance of a particular set of methods and assumptions. Thirdly, a state of crisis where anomalies that cannot be solved within the existing paradigm emerge and competing theories to address them follow. Fourthly, a revolutionary phase where some new paradigmatic approach becomes dominant and supplants the old. Shnieder (2009)[4] suggests that the Kuhnian phases are characterized by different kinds of scientific activity.

Newer approaches often build upon rather than replace older ones, but they also overlap and can exist within a state of competition. Scientists working within a particular paradigm often share methods, assumptions and values. In addition to supporting specific methods, research paradigms also influence things like the ambition and nature of research, the researcher-participant relationship and how the role of the researcher is understood.

Paradigm vs. theory

The terms 'paradigm' and 'theory' are often used interchangeably in social science. There is not a consensus among social scientists as to whether these are identical or distinct concepts. With that said, in this text, we will make a clear distinction between the two ideas because thinking about each concept separately is more useful for our purposes.

We define paradigm a set of common philosophical (ontological, epistemological, and axiological) assumptions that inform research. The four paradigms we describe in this section refer to patterns in how groups of researchers resolve philosophical questions. Some assumptions naturally make sense together, and paradigms grow out of researchers with shared assumptions about what is important and how to study it. Paradigms are like “analytic lenses” and a provide framework on top of which we can build theoretical and empirical knowledge (Kuhn, 1962).[5] Consider this video of an interview with world-famous physicist Richard Feynman in which he explains why "when you explain a 'why,' you have to be in some framework that you allow something to be true. Otherwise, you are perpetually asking why." In order to answer basic physics question like "what is happening when two magnets attract?" or a social work research question like "what is the impact of this therapeutic intervention on depression," you must understand the assumptions you are making about social science and the social world. Paradigmatic assumptions about objective and subjective truth support methodological choices like whether to conduct interviews or send out surveys, for example.

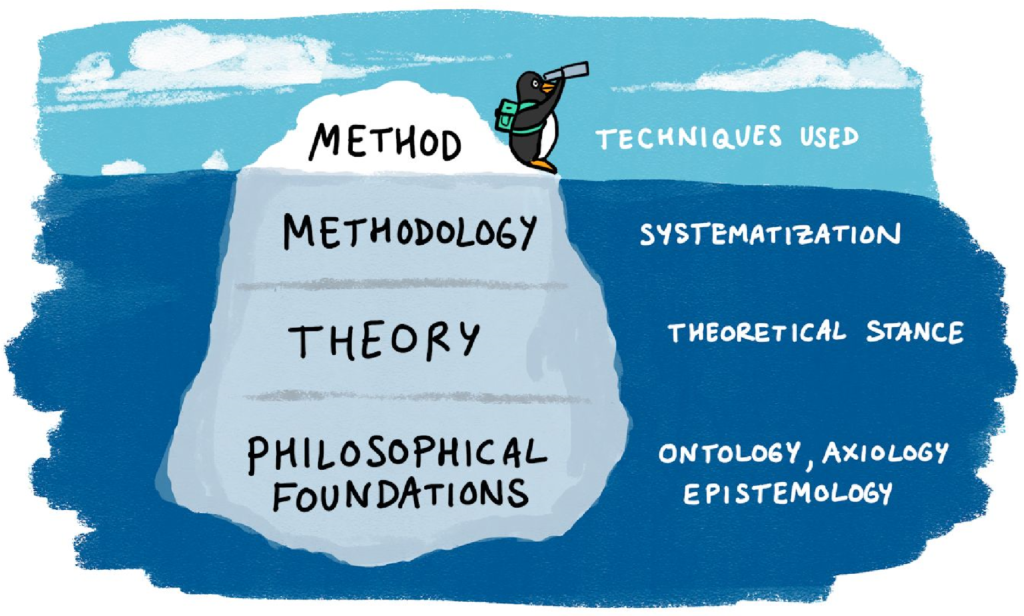

While paradigms are broad philosophical assumptions, theory is more specific, and refers to a set of concepts and relationships scientists use to explain the social world. Theories are more concrete, while paradigms are more abstract. Look back to Figure 7.1 at the beginning of this chapter. Theory helps you identify the concepts and relationships that align with your paradigmatic understanding of the problem. Moreover, theory informs how you will measure the concepts in your research question and the design of your project.

For both theories and paradigms, Kuhn's observation of scientific paradigms, crises, and revolutions is instructive for understanding the history of science. Researchers inherit institutions, norms, and ideas that are marked by the battlegrounds of theoretical and paradigmatic debates that stretch back hundreds of years. We have necessarily simplified this history into four paradigms: positivism, interpretivism, critical, and pragmatism. Our framework and explanation are inspired by the framework of Guba and Lincoln (1990)[6] and Burrell and Morgan (1979).[7] while also incorporating pragmatism as a way of resolving paradigmatic questions. Most of social work research and theory can be classified as belonging to one of these four paradigms, though this classification system represents only one of many useful approaches to analyzing social science research paradigms.

Building on our discussion in section 7.1 on objective vs. subjective epistemologies and ontologies, we will start with the difference between positivism and interpretivism. Afterward, we will link our discussion of axiology in section 7.2 with the critical paradigm. Finally, we will situate pragmatism as a way to resolve paradigmatic questions strategically. The difference between positivism and interpretivism is a good place to start, since the critical paradigm and pragmatism build on their philosophical insights.

It's important to think of paradigms less as distinct categories and more as a spectrum along which projects might fall. For example, some projects may be somewhat positivist, somewhat interpretivist, and a little critical. No project fits perfectly into one paradigm. Additionally, there is no paradigm that is more correct than the other. Each paradigm uses assumptions that are logically consistent, and when combined, are a useful approach to understanding the social world using science. The purpose of this section is to acquaint you with what research projects in each paradigm look like and how they are grounded in philosophical assumptions about social science.

You should read this section to situate yourself in terms of what paradigm feels most "at home" to both you as a person and to your project. You may find, as I have, that your research projects are more conventional and less radical than what feels most like home to you, personally. In a research project, however, students should start with their working question rather than their heart. Use the paradigm that fits with your question the best, rather than which paradigm you think fits you the best.

Interpretivism: Researcher as "empathizer"

Positivism is focused on generalizable truth. Interpretivism, by contrast, develops from the idea that we want to understand the truths of individuals, how they interpret and experience the world, their thought processes, and the social structures that emerge from sharing those interpretations through language and behavior. The process of interpretation (or social construction) is guided by the empathy of the researcher to understand the meaning behind what other people say.

Historically, interpretivism grew out of a specific critique of positivism: that knowledge in the human and social sciences cannot conform to the model of natural science because there are features of human experience that cannot objectively be “known”. The tools we use to understand objects that have no self-awareness may not be well-attuned to subjective experiences like emotions, understandings, values, feelings, socio-cultural factors, historical influences, and other meaningful aspects of social life. Instead of finding a single generalizable “truth,” the interpretivist researcher aims to generate understanding and often adopts a relativist position.

While positivists seek “the truth,” the social constructionist framework argues that “truth” varies. Truth differs based on who you ask, and people change what they believe is true based on social interactions. These subjective truths also exist within social and historical contexts, and our understanding of truth varies across communities and time periods. This is because we, according to this paradigm, create reality ourselves through our social interactions and our interpretations of those interactions. Key to the interpretivist perspective is the idea that social context and interaction frame our realities.

Researchers operating within this framework take keen interest in how people come to socially agree, or disagree, about what is real and true. Consider how people, depending on their social and geographical context, ascribe different meanings to certain hand gestures. When a person raises their middle finger, those of us in Western cultures will probably think that this person isn't very happy (not to mention the person at whom the middle finger is being directed!). In other societies around the world, a thumbs-up gesture, rather than a middle finger, signifies discontent (Wong, 2007).[8] The fact that these hand gestures have different meanings across cultures aptly demonstrates that those meanings are socially and collectively constructed. What, then, is the "truth" of the middle finger or thumbs up? As we've seen in this section, the truth depends on the intention of the person making the gesture, the interpretation of the person receiving it, and the social context in which the action occurred.

Qualitative methods are preferred as ways to investigate these phenomena. Data collected might be unstructured (or “messy”) and correspondingly a range of techniques for approaching data collection have been developed. Interpretivism acknowledges that it is impossible to remove cultural and individual influence from research, often instead making a virtue of the positionality of the researcher and the socio-cultural context of a study.

One common objection positivists levy against interpretivists is that interpretivism tends to emphasize the subjective over the objective. If the starting point for an investigation is that we can’t fully and objectively know the world, how can we do research into this without everything being a matter of opinion? For the positivist, this risk for confirmation bias as well as invalid and unreliable measures makes interpretivist research unscientific. Clearly, we disagree with this assessment, and you should, too. Positivism and interpretivism have different ontologies and epistemologies with contrasting notions of rigor and validity (for more information on assumptions about measurement, see Chapter 11 for quantitative validity and reliability and Chapter 20 for qualitative rigor). Nevertheless, both paradigms apply the values and concepts of the scientific method through systematic investigation of the social world, even if their assumptions lead them to do so in different ways. Interpretivist research often embraces a relativist epistemology, bringing together different perspectives in search of a trustworthy and authentic understanding or narrative.

Kivunja & Kuyini (2017)[9] describe the essential features of interpretivism as:

- The belief that truths are multiple and socially constructed

- The acceptance that there is inevitable interaction between the researcher and his or her research participants

- The acceptance that context is vital for knowledge and knowing

- The belief that knowledge can be value laden and the researcher's values need to be made explicit

- The need to understand specific cases and contexts rather deriving universal laws that apply to everyone, everywhere.

- The belief that causes and effects are mutually interdependent, and that causality may be circular or contradictory

- The belief that contextual factors need to be taken into consideration in any systematic pursuit of understanding

One important clarification: it's important to think of the interpretivist perspective as not just about individual interpretations but the social life of interpretations. While individuals may construct their own realities, groups—from a small one such as a married couple to large ones such as nations—often agree on notions of what is true and what “is” and what "is not." In other words, the meanings that we construct have power beyond the individuals who create them. Therefore, the ways that people and communities act based on such meanings is of as much interest to interpretivists as how they were created in the first place. Theories like social constructionism, phenomenology, and symbolic interactionism are often used in concert with interpretivism.

Is interpretivism right for your project?

An interpretivist orientation to research is appropriate when your working question asks about subjective truths. The cause-and-effect relationships that interpretivist studies produce are specific to the time and place in which the study happened, rather than a generalizable objective truth. More pragmatically, if you picture yourself having a conversation with participants like an interview or focus group, then interpretivism is likely going to be a major influence for your study.

Positivists critique the interpretivist paradigm as non-scientific. They view the interpretivist focus on subjectivity and values as sources of bias. Positivists and interpretivists differ on the degree to which social phenomena are like natural phenomena. Positivists believe that the assumptions of the social sciences and natural sciences are the same, while interpretivists strongly believe that social sciences differ from the natural sciences because their subjects are social creatures.

Similarly, the critical paradigm finds fault with the interpretivist focus on the status quo rather than social change. Although interpretivists often proceed from a feminist or other standpoint theory, the focus is less on liberation than on understanding the present from multiple perspectives. Other critical theorists may object to the consensus orientation of interpretivist research. By searching for commonalities between people's stories, they may erase the uniqueness of each individual's story. For example, while interpretivists may arrive at a consensus definition of what the experience of "coming out" is like for people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer, it cannot represent the diversity of each person's unique "coming out" experience and what it meant to them. For example, see Rosario and colleagues' (2009)[10] critique the literature on lesbians "coming out" because previous studies did not addressing how appearing, behaving, or identifying as a butch or femme impacted the experience of "coming out" for lesbians.

Exercises

- From your literature search, identify an empirical article that uses qualitative methods to answer a research question similar to your working question or about your research topic.

- Review the assumptions of the interpretivist research paradigm.

- Discuss in a few sentences how the author's conclusions are based on some of these paradigmatic assumptions. How might a researcher operating from a different paradigm (like positivism or the critical paradigm) critique the conclusions of this study?

Critical paradigm: Researcher as "activist"

As we've discussed a bit in the preceding sections, the critical paradigm focuses on power, inequality, and social change. Although some rather diverse perspectives are included here, the critical paradigm, in general, includes ideas developed by early social theorists, such as Max Horkheimer (Calhoun et al., 2007),[11] and later works developed by feminist scholars, such as Nancy Fraser (1989).[12] Unlike the positivist paradigm, the critical paradigm assumes that social science can never be truly objective or value-free. Furthermore, this paradigm operates from the perspective that scientific investigation should be conducted with the express goal of social change. Researchers in the critical paradigm foreground axiology, positionality and values . In contrast with the detached, “objective” observations associated with the positivist researcher, critical approaches make explicit the intention for research to act as a transformative or emancipatory force within and beyond the study.

Researchers in the critical paradigm might start with the knowledge that systems are biased against certain groups, such as women or ethnic minorities, building upon previous theory and empirical data. Moreover, their research projects are designed not only to collect data, but to impact the participants as well as the systems being studied. The critical paradigm applies its study of power and inequality to change those power imbalances as part of the research process itself. If this sounds familiar to you, you may remember hearing similar ideas when discussing social conflict theory in your human behavior in the social environment (HBSE) class.[13] Because of this focus on social change, the critical paradigm is a natural home for social work research. However, we fall far short of adopting this approach widely in our profession's research efforts.

Is the critical paradigm right for your project?

Every social work research project impacts social justice in some way. What distinguishes critical research is how it integrates an analysis of power into the research process itself. Critical research is appropriate for projects that are activist in orientation. For example, critical research projects should have working questions that explicitly seek to raise the consciousness of an oppressed group or collaborate equitably with community members and clients to addresses issues of concern. Because of their transformative potential, critical research projects can be incredibly rewarding to complete. However, partnerships take a long time to develop and social change can evolve slowly on an issue, making critical research projects a more challenging fit for student research projects which must be completed under a tight deadline with few resources.

Positivists critique the critical paradigm on multiple fronts. First and foremost, the focus on oppression and values as part of the research process is seen as likely to bias the research process, most problematically, towards confirmation bias. If you start out with the assumption that oppression exists and must be dealt with, then you are likely to find that regardless of whether it is truly there or not. Similarly, positivists may fault critical researchers for focusing on how the world should be, rather than how it truly is. In this, they may focus too much on theoretical and abstract inquiry and less on traditional experimentation and empirical inquiry. Finally, the goal of social transformation is seen as inherently unscientific, as science is not a political practice.

Interpretivists often find common cause with critical researchers. Feminist studies, for example, may explore the perspectives of women while centering gender-based oppression as part of the research process. In interpretivist research, the focus is less on radical change as part of the research process and more on small, incremental changes based on the results and conclusions drawn from the research project. Additionally, some critical researchers' focus on individuality of experience is in stark contrast to the consensus-orientation of interpretivists. Interpretivists seek to understand people's true selves. Some critical theorists argue that people have multiple selves or no self at all.

Exercises

- From your literature search, identify an article relevant to your working question or broad research topic that uses a critical perspective. You should look for articles where the authors are clear that they are applying a critical approach to research like feminism, anti-racism, Marxism and critical theory, decolonization, anti-oppressive practice, or other social justice-focused theoretical perspectives. To target your search further, include keywords in your queries to research methods commonly used in the critical paradigm like participatory action research and community-based participatory research. If you have trouble identifying an article for this exercise, consult your professor for some help. These articles may be more challenging to find, but reviewing one is necessary to get a feel for what research in this paradigm is like.

- Review the assumptions of the critical research paradigm.

- Discuss in a few sentences how the author's conclusions are based on some of these paradigmatic assumptions. How might a researcher operating from different assumptions (like values-neutrality or researcher as neutral and unbiased) critique the conclusions of this study?

Pragmatism: Researcher as "strategist"

“Essentially, all models are wrong but some are useful.” (Box, 1976)[14]

Pragmatism is a research paradigm that suspends questions of philosophical ‘truth’ and focuses more on how different philosophies, theories, and methods can be used strategically to provide a multidimensional view of a topic. Researchers employing pragmatism will mix elements of positivist, interpretivist, and critical research depending on the purpose of a particular project and the practical constraints faced by the researcher and their research context. We favor this approach for student projects because it avoids getting bogged down in choosing the "right" paradigm and instead focuses on the assumptions that help you answer your question, given the limitations of your research context. Student research projects are completed quickly and moving in the direction of pragmatism can be a route to successfully completing a project. Your project is a representation of what you think is feasible, ethical, and important enough for you to study.

The crucial consideration for the pragmatist is whether the outcomes of research have any real-world application, rather than whether they are “true.” The methods, theories, and philosophies chosen by pragmatic researchers are guided by their working question. There are no distinctively pragmatic research methods since this approach is about making judicious use whichever methods fit best with the problem under investigation. Pragmatic approaches may be less likely to prioritize ontological, epistemological or axiological consistency when combining different research methods. Instead, the emphasis is on solving a pressing problem and adapting to the limitations and opportunities in the researchers' context.

Adopt a multi-paradigmatic perspective

Believe it or not, there is a long literature of acrimonious conflict between scientists from positivist, interpretivist, and critical camps (see Heineman-Pieper et al., 2002[15] for a longer discussion). Pragmatism is an old idea, but it is appealing precisely because it attempts to resolve the problem of multiple incompatible philosophical assumptions in social science. To a pragmatist, there is no "correct" paradigm. All paradigms rely on assumptions about the social world that are the subject of philosophical debate. Each paradigm is an incomplete understanding of the world, and it requires a scientific community using all of them to gain a comprehensive view of the social world. This multi-paradigmatic perspective is a unique gift of social work research, as our emphasis on empathy and social change makes us more critical of positivism, the dominant paradigm in social science.

We offered the metaphors of expert, empathizer, activist, and strategist for each paradigm. It's important not to take these labels too seriously. For example, some may view that scientists should be experts or that activists are biased and unscientific. Nevertheless, we hope that these metaphors give you a sense of what it feels like to conduct research within each paradigm.

One of the unique aspects of paradigmatic thinking is that often where you think you are most at home may actually be the opposite of where your research project is. For example, in my graduate and doctoral education, I thought I was a critical researcher. In fact, I thought I was a radical researcher focused on social change and transformation. Yet, often times when I sit down to conceptualize and start a research project, I find myself squarely in the positivist paradigm, thinking through neat cause-and-effect relationships that can be mathematically measured. There is nothing wrong with that! Your task for your research project is to find the paradigm that best matches your research question. Think through what you really want to study and how you think about the topic, then use assumptions of that paradigm to guide your inquiry.

Another important lesson is that no research project fits perfectly in one paradigm or another. Instead, there is a spectrum along which studies are, to varying degrees, interpretivist, positivist, and critical. For example, all social work research is a bit activist in that our research projects are designed to inform action for change on behalf of clients and systems. However, some projects will focus on the conclusions and implications of projects informing social change (i.e., positivist and interpretivist projects) while others will partner with community members and design research projects collaboratively in a way that leads to social change (i.e. critical projects). In section 7.5, we will describe a pragmatic approach to research design guided by your paradigmatic and theoretical framework.

Key Takeaways

- Social work research falls, to some degree, in each of the four paradigms: positivism, interpretivism, critical, and pragmatist.

- Adopting a pragmatic, multi-paradigmatic approach to research makes sense for student researchers, as it directs students to use the philosophical assumptions and methodological approaches that best match their research question and research context.

- Research in all paradigms is necessary to come to a comprehensive understanding of a topic, and social workers must be able to understand and apply knowledge from each research paradigm.

Exercises

- Describe which paradigm best fits your perspective on the world and which best fits with your project.

- Identify any similarities and differences in your personal assumptions and the assumption your research project relies upon. For example, are you a more critical and radical thinker but have chosen a more "expert" role for yourself in your research project?

15.2 Multiparadigmatic research: An example

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Apply the assumptions of each paradigm to your project

- Summarize what aspects of your project stem from positivist, interpretivist, or critical assumptions

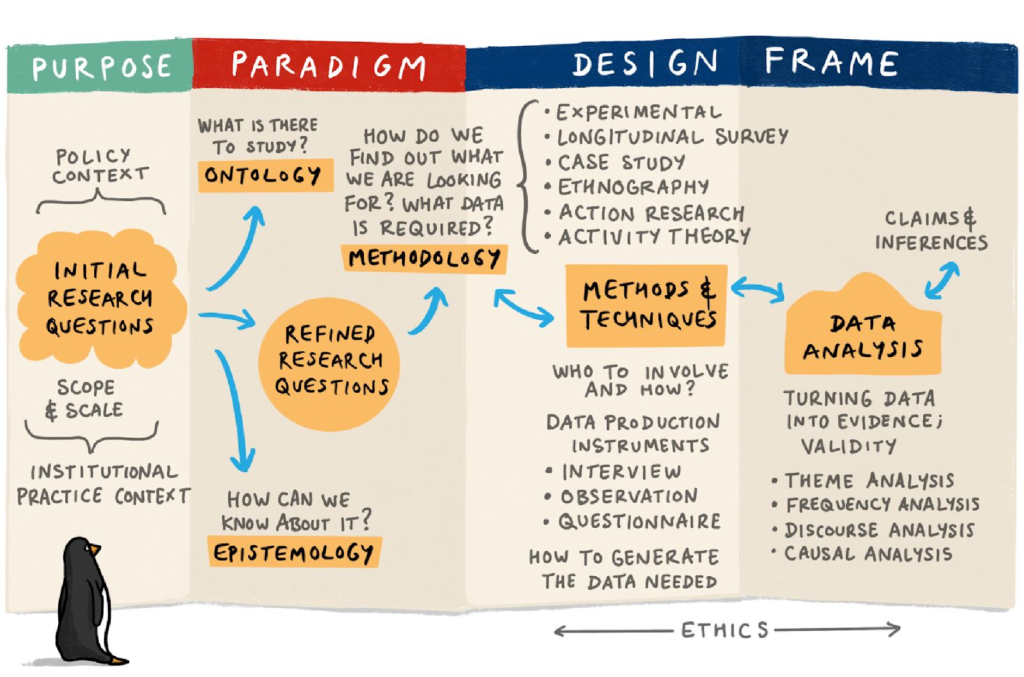

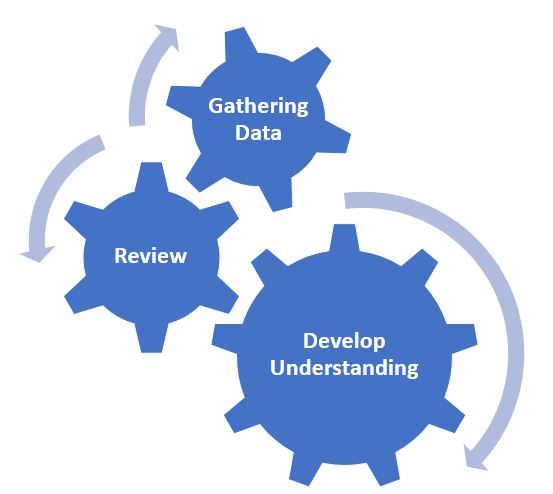

In the previous sections, we reviewed the major paradigms and theories in social work research. In this section, we will provide an example of how to apply theory and paradigm in research. This process is depicted in Figure 7.2 below with some quick summary questions for each stage. Some questions in the figure below have example answers like designs (i.e., experimental, survey) and data analysis approaches (i.e., discourse analysis). These examples are arbitrary. There are a lot of options that are not listed. So, don't feel like you have to memorize them or use them in your study.

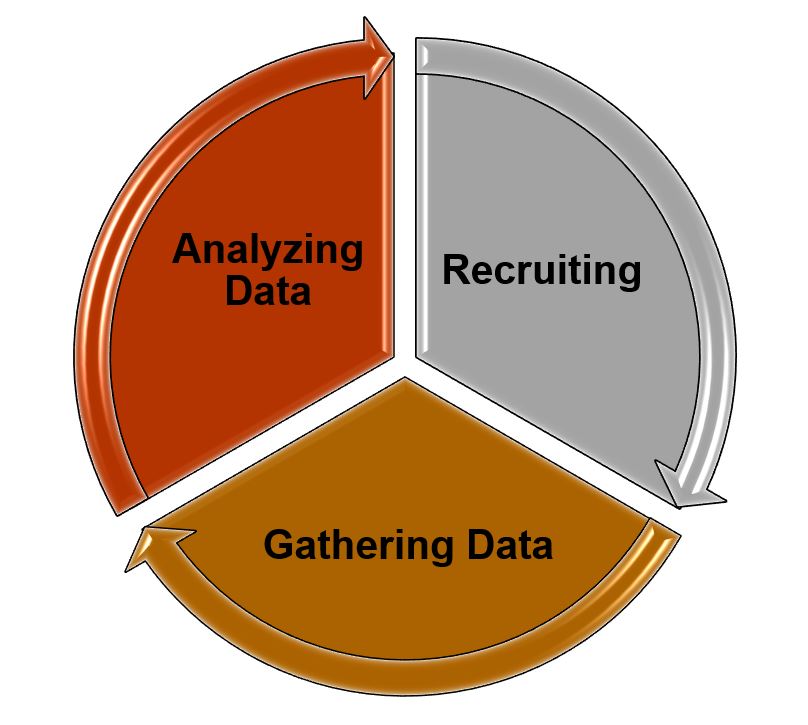

This diagram (taken from an archived Open University (UK) course entitled E89-Educational Inquiry) shows one way to visualize the research design process. While research is far from linear, in general, this is how research projects progress sequentially. Researchers begin with a working question, and through engaging with the literature, develop and refine those questions into research questions (a process we will finalize in Chapter 9). But in order to get to the part where you gather your sample, measure your participants, and analyze your data, you need to start with paradigm. Based on your work in section 7.3, you should have a sense of which paradigm or paradigms are best suited to answering your question. The approach taken will often reflect the nature of the research question; the kind of data it is possible to collect; and work previously done in the area under consideration. When evaluating paradigm and theory, it is important to look at what other authors have done previously and the framework used by studies that are similar to the one you are thinking of conducting.

Once you situate your project in a research paradigm, it becomes possible to start making concrete choices about methods. Depending on the project, this will involve choices about things like:

- What is my final research question?

- What are the key variables and concepts under investigation, and how will I measure them?

- How do I find a representative sample of people who experience the topic I'm studying?

- What design is most appropriate for my research question?

- How will I collect and analyze data?

- How do I determine whether my results describe real patterns in the world or are the result of bias or error?

The data collection phase can begin once these decisions are made. It can be very tempting to start collecting data as soon as possible in the research process as this gives a sense of progress. However, it is usually worth getting things exactly right before collecting data as an error found in your approach further down the line can be harder to correct or recalibrate around.

Designing a study using paradigm and theory: An example

Paradigm and theory have the potential to turn some people off since there is a lot of abstract terminology and thinking about real-world social work practice contexts. In this section, I'll use an example from my own research, and I hope it will illustrate a few things. First, it will show that paradigms are really just philosophical statements about things you already understand and think about normally. It will also show that no project neatly sits in one paradigm and that a social work researcher should use whichever paradigm or combination of paradigms suit their question the best. Finally, I hope it is one example of how to be a pragmatist and strategically use the strengths of different theories and paradigms to answering a research question. We will pick up the discussion of mixed methods in the next chapter.

Thinking as an expert: Positivism

In my undergraduate research methods class, I used an open textbook much like this one and wanted to study whether it improved student learning. You can read a copy of the article we wrote on based on our study. We'll learn more about the specifics of experiments and evaluation research in Chapter 13, but you know enough to understand what evaluating an intervention might look like. My first thought was to conduct an experiment, which placed me firmly within the positivist or "expert" paradigm.

Experiments focus on isolating the relationship between cause and effect. For my study, this meant studying an open textbook (the cause, or intervention) and final grades (the effect, or outcome). Notice that my position as "expert" lets me assume many things in this process. First, it assumes that I can distill the many dimensions of student learning into one number—the final grade. Second, as the "expert," I've determined what the intervention is: indeed, I created the book I was studying, and applied a theory from experts in the field that explains how and why it should impact student learning.

Theory is part of applying all paradigms, but I'll discuss its impact within positivism first. Theories grounded in positivism help explain why one thing causes another. More specifically, these theories isolate a causal relationship between two (or more) concepts while holding constant the effects of other variables that might confound the relationship between the key variables. That is why experimental design is so common in positivist research. The researcher isolates the environment from anything that might impact or bias the cause and effect relationship they want to investigate.

But in order for one thing to lead to change in something else, there must be some logical, rational reason why it would do so. In open education, there are a few hypotheses (though no full-fledged theories) on why students might perform better using open textbooks. The most common is the access hypothesis, which states that students who cannot afford expensive textbooks or wouldn't buy them anyway can access open textbooks because they are free, which will improve their grades. It's important to note that I held this theory prior to starting the experiment, as in positivist research you spell out your hypotheses in advance and design an experiment to support or refute that hypothesis.

Notice that the hypothesis here applies not only to the people in my experiment, but to any student in higher education. Positivism seeks generalizable truth, or what is true for everyone. The results of my study should provide evidence that anyone who uses an open textbook would achieve similar outcomes. Of course, there were a number of limitations as it was difficult to tightly control the study. I could not randomly assign students or prevent them from sharing resources with one another, for example. So, while this study had many positivist elements, it was far from a perfect positivist study because I was forced to adapt to the pragmatic limitations of my research context (e.g., I cannot randomly assign students to classes) that made it difficult to establish an objective, generalizable truth.

Thinking like an empathizer: Interpretivism

One of the things that did not sit right with me about the study was the reliance on final grades to signify everything that was going on with students. I added another quantitative measure that measured research knowledge, but this was still too simplistic. I wanted to understand how students used the book and what they thought about it. I could create survey questions that ask about these things, but to get at the subjective truths here, I thought it best to use focus groups in which students would talk to one another with a researcher moderating the discussion and guiding it using predetermined questions. You will learn more about focus groups in Chapter 18.