2 Starting your research project

Chapter Outline

- Proposing a research project

- Developing a working question

- Positionality

- First thoughts and information need

- Evaluating online resources (11 minute read)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter discuss substance use disorders, mental health disorders and therapies, obesity, poverty, gun violence, gang violence, school discipline, racism and hate groups, domestic violence, trauma and triggers, incarceration, child neglect and abuse, bullying, self-harm and suicide, racial discrimination in housing, burnout in helping professions, and sex trafficking of indigenous women.

2.1 Proposing a research project

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe the stages of a research project

- Assess whether you need to carry out your proposed research project

- Critique the traditional role of researchers and identify how action research addresses these issues

Most research methods courses are designed to help students propose (and carry out) a research project. But what is a research project? In a very important sense, a research project is whatever your instructor says it is in the course syllabus. Examine the specific prompt from your instructor rather than relying on the summaries in this chapter. Fortunately, almost all classes are designed to do roughly the same thing: assist students with proposing a research study.

A research proposal, is a document produced by researchers that reviews the literature relevant to their topic and describes the methods they will use to conduct an empirical study. Part 1 of this textbook is designed to help you write a literature review. Parts 2 & 3 are designed to help you figure out which methods you will use in your study, carry them out, and report the results.

You can think of a research proposal like creating a recipe. If you are a chef trying to cook a new dish from scratch, you would probably start by looking at other recipes. You might cook a few of them and come up with ideas about how to create your own version of the dish. Writing your recipe is a process of trial and error, and you will likely revise your proposal many times over the course of the semester. This textbook and its exercises designed to get you working on your project little by little, so that by the time you turn in your final research proposal, you’ll be confident it represents the best way to answer your question.

Of course, like with any time I cook, you never quite know how it will turn out. What matters for scientists in the end isn’t whether your data proves your hypothesis correct or your data collection goes according to plan. Instead, what matters is that you report your results (warts and all) as honestly and openly as possible to inform others engaged in scientific inquiry.

Is writing a research proposal a useful skill for a social worker? On one hand, you probably won’t be writing research proposals for a living. Social work research is an under-loved specialization. But the same structure of a research proposal (literature review + methods) is used in grant applications. Grant writing is a part of meso-level social work practice, particularly agency leadership. In macro practice, a policy advocate or public administrator would use a similar structure to propose a government-funded demonstration project for an emerging practice in evidence-based care.

Research proposals are helpful for securing funding for student research projects. If you are using this resource to create an honors or graduate thesis, you may need to submit (and defend) your research proposal prior to data collection. If you plan to travel to regional or national conferences to present your results, you will likely need to submit a research proposal.

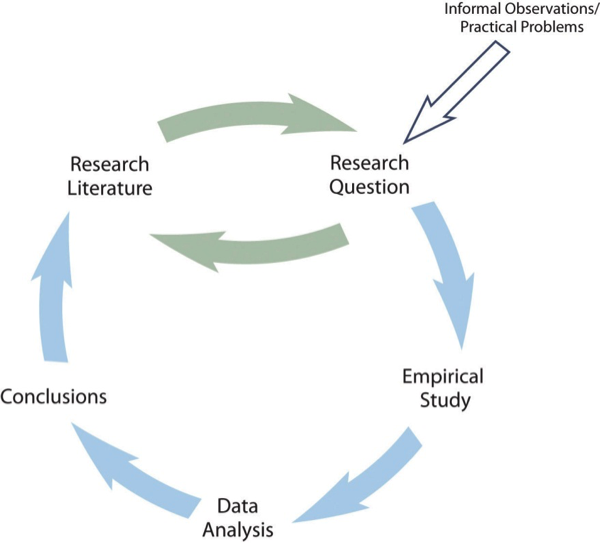

Steps of a research project

Figure 2.1 indicates the steps of the research project. Right now, we are in the top right corner, using your informal observations from your practice experience and lived experience to form a working draft of your research question. In the next three chapters, you’ll learn how to find and evaluate scholarly literature on your topic. After thoroughly evaluating the literature, you’ll conceptualize an empirical study based on a research question you create. This is a research proposal…a proposed set of research methods and the scientific literature demonstrating how those methods will help you answer your research question.

Must I collect data?

In an introductory research methods course, students almost always have to write a research proposal. Later, students may have to carry out their proposed study: collect data, analyze it, and present it. This is often a part of a thesis or capstone project. Each university approaches research methods education differently. Check with your professor on whether you are required to carry out the project you propose to do in your research proposal.

If you are in my graduate classroom, you will only need to propose a hypothetical project that could work, in theory. We learn statistics and qualitative analysis in our program evaluation course using data I’ve already collected. If you are planning to complete the research project, you will have to pay more attention to the practical and ethical considerations during project conceptualization. Your professor may suggest using secondary data, practitioner interviews, or other data sources with low barriers to access.

If you have to collect data, consult Chapter 2 of another research textbook I co-authored. It reviews how students can navigate practical and ethical considerations at the beginning of a research project. Creating a feasible data collection approach should be prioritized at the outset, if needed.

Participatory and community-engaged approaches

Let’s critically examine your role as the researcher. Following along with the steps in a research project, you start studying the literature your topic, find a place where you can add to scientific knowledge, and conduct your study. But why are you the person who gets to decide what is important? Just as clients are the experts on their lives, members of your target population are the experts on their lives. What does it mean for a group of people to be researched on, rather than researched with? How can we better respect the knowledge and self-determination of community members?

The research cycle, as pictured above, puts the researcher’s worldview and observations at the center of the scientific process. Getting the perspective of people with lived experience provides another layer to conceptualization of research projects in social work. It is unlikely that you will end up as a solo researcher independently pursuing your own research questions. Instead, social work research questions are usually attached to a client, community, or agency need. Social work researchers also try to develop longstanding relationships with communities, seeking input throughout the research process.

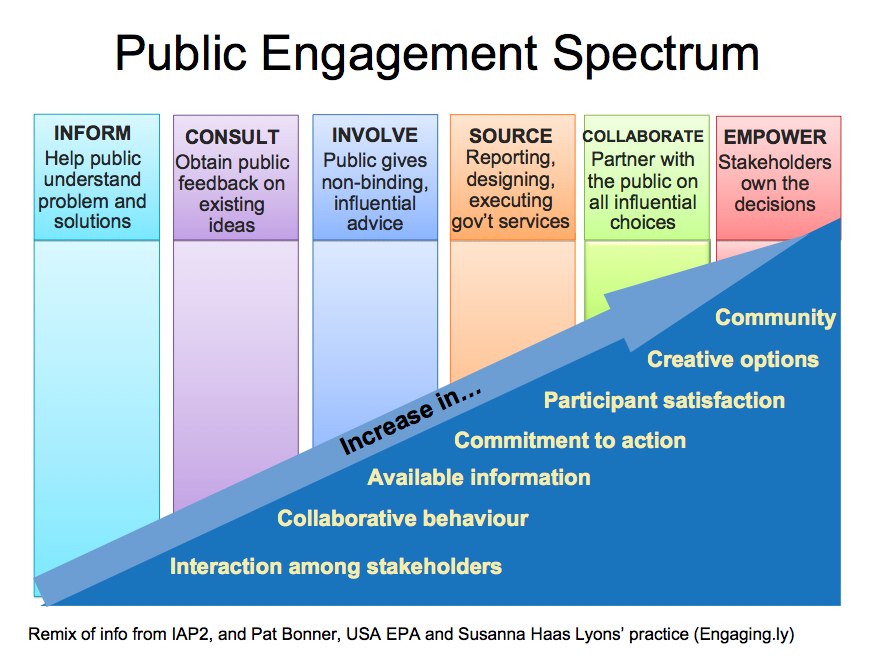

The figure below describes how community-engaged research starts from a different place. Rather than the informal observations of scientists or gaps in previous scientific publications, community members bring forth issues that are most pressing to their life, and work with researchers as consultants whose impact on the community will last beyond the data collection.

A traditional scientist might look at the literature or use their practice wisdom to formulate a question for quantitative or qualitative research. A community-engaged researcher, on the other hand, would consult with people in target population and community to see what they believe the most pressing issues are and what their proposed solutions may be. Social work research projects often try to prove obviously true hypotheses like: feeding children helps them learn, housing people who are homeless is better for their health, and so forth. Thus, it is often about finding the question with the most community impact rather than a unique or clever idea from a scientists.

A different way to begin your research project is to talk with members of the target population and those who are knowledgeable about the community in your inquiry. Perhaps there is a community-led organization you can partner with on a research project. The researcher’s role in this case would be more similar to a consultant, someone with specialized knowledge about research who can help communities study problems they consider to be important. The social worker is a co-investigator, and community members are equal partners in the research project. Each has a type of knowledge—scientific expertise vs. lived experience—that should inform the research process.

The community focus highlights something important about student projects: they are localized. Student projects can dedicate themselves to issues at a single agency or within a service area. With a local scope, student researchers can bring about change in their community. See the short video from the University of California-Berkeley which can help you distinguish community-engaged research from things like service learning.

With rare exceptions, student projects are unlikely to be community-engaged because the project is only a semester long, leaving little room for the long-term relationships necessary for effective community-engaged research. At the same time, this advice might unnecessarily limit an ambitious and diligent student who wanted to investigate something more complex. For example, here is a Vice News article about MSW student Christine Stark’s work on sex trafficking of indigenous women. Student projects have the potential to address sensitive and politically charged topics. With support from faculty and community partners, student projects can become more comprehensive. The results of your project should accomplish something. Social work research is about creating change, and you will find the work of completing a research project more rewarding and engaging if you can envision the change your project will create.

In addition to community-engaged research, students may want to explore participatory research models in which students research their local communities, universities, academic programs, and so forth. Consider this resource on how to research your institution by Rine Vieth. As a student, you are one of the groups on campus with the least power (others include custodial staff, administrative staff, contingent and adjunct faculty). It is often necessary that you organize within your cohort of MSW students for change within the program. Not only is it an excellent learning opportunity to practice your advocacy skills, you can use raw data that is publicly available (such as those linked in the guide) or create your own raw data to inform change. The collaborative and transformative focus of student research projects like these can be impactful learning experiences, and students should consider projects that will lead to some small change in both themselves and their communities.

Baum and colleagues (2006)[1] define participatory action research as “collective, self-reflective inquiry that researchers and participants undertake so they can understand and improve upon the practices in which they participate and the situations in which they find themselves” (p. 854).

In addition to broader community and agency impacts, student research projects can have an impact on a university or academic program. Social workers who engage in action research don’t just go it alone; instead, they collaborate with the people who are affected by the research at each stage in the process. According to Healy (2001),[2] the assumptions of participatory action research are that (a) oppression is caused by macro-level structures such as patriarchy and capitalism; (b) research should expose and confront the powerful; (c) researcher and participant relationships should be equal, with equitable distribution of research tasks and roles; and (d) research should result in consciousness-raising and collective action.

Consistent with social work values, action research supports the self-determination of oppressed groups and privileges their voice and understanding through the conceptualization, design, data collection, data analysis, and dissemination processes of research. Action research has multiple origins across the globe, including Kurt Lewin’s psychological experiments in the US and Paulo Friere’s literacy and education programs (Adelman, 1993; Reason, 1994).[3] Over the years, action research has become increasingly popular among scholars who wish for their work to have tangible outcomes that benefit the groups they study. We will return to similar ideas in Part 3 of the textbook when we discuss qualitative research methods, though action research can certainly be used with quantitative research methods, as well.

My favorite participatory action research study conducted by a social work student from a recent literature review as Sophie Gephardt’s undergraduate thesis from the Ohio State University. It used quantitative methods to estimate the prevalence of food insecurity among her social work cohort across multiple campuses. It also used qualitative methods to describe the impact of these issues on students’ wellbeing, academic performance, and health. Student-authored studies on unpaid internships present a totally unique perspective from faculty-authored studies. Consider this as an analogy. Just like your faculty likely do not understand how unpaid internships impact student life, researchers outside of the communities they study lack knowledge that could help them attend to important issues, conceptualize them appropriately, and design research projects for community impact.

Key Takeaways

- Research exists in a cycle. Your research project will follow this cycle, beginning from reading literature (where you are now), to proposing a study, to completing a research project, and finally, to publishing the results.

- Traditionally, researchers did not consult target populations and communities prior to formulating a research question. Action research proposes a more community-engaged model in which researchers are consultants that help communities research topics of import to them.

- Just because we’ve advised you to keep your project simple and small doesn’t mean you must do so! There are excellent examples of student research projects that have created real change in the world.

Exercises

- Look at the requirements for your instructor’s research proposal assignment. Make sure you understand what is expected.

2.2 Developing a working question

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Brainstorm topics you may want to investigate as part of a research project

- Define your target population and describe how your study will impact that population

- Identify the aim of your study

- Classify your project as descriptive, exploratory, explanatory, or evaluative

- Develop a working question

Research methods is a unique class in that you get to decide what you want to learn about. Perhaps you came to your MSW program with a specific issue you were passionate about. In my MSW program, I wanted to learn about the best interventions to use with people who have substance use disorders. This was in line with my future career plans, which included working in a clinical setting with clients with co-occurring mental health and substance use issues. I suggest you start by thinking about your future practice goals and create a research project that addresses a topic that represents an area of social work you are passionate about.

For those of you without a specific direction, don’t worry. Many people enter their MSW program without an exact topic in mind they want to study. Throughout the program, you will be exposed to different populations, theories, practice interventions, and policies that will spark your interest. Think back to papers you enjoyed researching and writing in other classes. You may want to continue studying the same topic. Research methods will enable you to gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of a topic or issue.

If you already have practice experience in social work through employment, an internship, or volunteer work, think about practice issues you noticed in the placement. Do you have any idea of how to better address client needs? Do you need to learn more about existing interventions or the programs that fund your agency? Use this class as an opportunity to engage with your previous field experience in greater detail. Begin with “what” and “why” questions and then expand on those. For example, what are the most effective methods of treating severe depression among a specific population? Or why are people receiving food assistance more likely to be obese?

You could also ask a professor at your school about possible topics. Read your department’s website to learn about the faculty’s research interests, which may surprise you. Most departmental websites post the curriculum vitae (CV) of faculty, which lists their publications, credentials, and interests. You can also look on LinkedIn or Google Scholar. For those of you interested in doctoral study, this process is particularly important. Students often pick schools based on professors they want to learn from or research initiatives they want to join.

Once you have a potential idea, start reading! A simple web search should bring you some basic information about your topic. News articles can reveal new or controversial information. Apply the techniques you learn at the end of this chapter to get to high-quality information. You may also want to look at encyclopedias or textbooks, materials designed to be consumed by people with little knowledge about the topic.

Writing a working question

There are lots of great research topics. Perhaps your topic is a client population—for example, youth who identify as LGBTQ+ or visitors to a local health clinic. In other cases, your topic may be a social problem, such as gang violence, or a social policy or program, such as zero-tolerance policies in schools. Alternately, maybe there are interventions such as dialectical behavioral therapy or applied behavior analysis that interest you.

It’s a good idea to keep it simple when you’re starting your project. Choose a topic that can be easily defined and explored. Your study cannot focus on everything that is important about your topic. A study on gun violence might address only one system, for example schools, while only briefly mentioning other systems that impact gun violence like families or social media. That doesn’t mean it’s a bad study! Every study presents only a small picture of a larger, more complex and multifaceted issue. The sooner you can arrive at something specific and clear that you want to study, the better off your project will be.

Whatever your topic idea, begin to think about it in terms of a question. What do you really want to know about the topic? As a warm-up exercise, try dropping a possible topic idea into one of the blank spaces below. The questions may help bring your subject into sharper focus and bring you closer towards developing your topic.

- What does ___ mean?

- What are the causes of ___?

- What are the consequences of ___?

- What are the component parts of ___?

- How does ___ impact ___?

- What is it like to experience ___?

- What is the relationship between _____ and the outcome of ____?

- What case can be made for or against ___?

- What are the risk/protective factors for ___?

- How do people think about ___?

Take a minute right now and write down a question you want to answer. Even if it doesn’t seem perfect, it is important to start somewhere. Make sure your research topic is relevant to social work. You’d be surprised how much of the world that encompasses. It’s not just research on mental health treatments or child welfare services. Social workers can study things like the pollution of irrigation systems and entrepreneurship in women, among other topics. The only requirement is your research must inform action to address social problems faced by target populations.

Because research is an iterative process, one that you will revise over and over, your question will continue to evolve. As you progress through this textbook, you’ll learn how to refine your question and include the necessary components for proper qualitative and quantitative research questions. Your question will also likely change as you engage with the literature on your topic. You will learn new and important concepts that may shift your focus or clarify your original ideas. Trust that a strong question will emerge from this process. A good researcher must be comfortable with altering their question as a result of scientific inquiry.

Very often, our students will email us in the first few weeks of class and ask if they have a good research topic. We love student emails! But just to reassure you if you’re about to send a panicked email to your professor, as long as you are interested in dedicating a semester or two learning about your topic, it will make a good research topic. That’s why we would advise you to focus on how much you like this topic, so that three months from now you are still motivated to complete your project. Your project should have meaning to you.

Empirical vs. ethical questions

When it comes to research questions, social science is best equipped to answer empirical questions—those that can be answered by real experience in the real world—as opposed to ethical questions—questions about which people have moral opinions and that may not be answerable in reference to the real world. While social workers have explicit ethical obligations (e.g., service, social justice), research projects ask empirical questions to help actualize and support the work of upholding those ethical principles.

Unfortunately, it is an ethical question, not an empirical one. To answer that question, you would have to draw on philosophy and morality, answering what it is about human nature and society that allows such unjust outcomes. However, you could not answer that question by gathering data about people in the real world. If I asked people that question, they would likely give me their opinions about drugs, gender-based violence, and the criminal justice system. But I wouldn’t get the real answer about why our society tolerates such an imbalance in punishment.

As the students worked on the project through the semester, they continued to focus on the topic of sexual assault in the criminal justice system. Their research question became more empirical because they read more empirical articles about their topic. One option that they considered was to evaluate intervention programs for perpetrators of sexual assault to see if they reduced the likelihood of committing sexual assault again. Another option they considered was seeing if counties or states with higher than average jail sentences for sexual assault perpetrators had lower rates of re-offense for sexual assault. These projects addressed the ethical question of punishing perpetrators of sexual violence but did so in a way that gathered and analyzed empirical real-world data. Our job as social work researchers is to gather social facts about social work issues, not to judge or determine morality.

Aim & target population

Based on your working question, think about what you hope to accomplish with your study. This is the aim of your research project. As you will recall from section 1.4, social work research is research for action. Social workers engage in research to help people. Think about your working question. Why do you want to answer it? What impact would answering your question have?

In my MSW program, I began my research by looking at ways to intervene with people who have substance use disorders. My foundation year placement was in an inpatient drug treatment facility that used 12-step facilitation as its primary treatment modality. I observed that this approach differed significantly from others I had been exposed to, especially the idea of powerlessness over drugs and drug use. My working question started as “what are the alternatives to 12-step treatment for people with substance use issues and are they more effective?” The aim of my project was to determine whether different treatment approaches might be more effective, and I suspected that self-determination and powerlessness were important.

It’s important to note that my working question contained a target population—people with substance use disorders. A target population is the group of people that will benefit the most. I envisioned I would help the field of social work to think through how to better meet clients where they were at, specific to the problem of substance use. I was studying to be a clinical social worker, so naturally, I formulated a micro-level question. Yet, the question also has implications for meso- and macro-level practice. If other treatment methods are more effective than 12-step facilitation, then we should direct more public money towards providing more effective therapies for people who use substances. We may also need to train the substance use professionals to use new treatment methodologies.

Exercises

Just as a reminder, exercises are designed to help you create your individual research proposal. I designed these activities to break down your proposal into small but manageable chunks. I suggest completing each exercise so you can apply what you are learning to your individual research project, as the exercises in each section and each chapter build on one another.

If you haven’t done so already, you can create a document in a word processor on your computer or in a written notebook with your answers to each exercise.

- Write down your working question.

- Is it more oriented towards micro-, meso-, or macro-level practice?

- What implications would answering your question have at each level of the ecosystem?

Asking yourself whether your project is more micro, meso, or macro is a good check to see if your project is well-focused. A project that seems like it could be all of those might have too many components or try to study too much. Consider identifying one ecosystem level your project will focus on, and you can interpret and contextualize your findings at the other levels of analysis.

Exploration, description, and explanation

Social science is a big place. Looking at the various empirical studies in the literature, there is a lot of diversity—from focus groups with clients and families to multivariate statistical analysis of large population surveys conducted online. Ultimately, all of social science can be described as one of three basic types of research studies. As you develop your research question, consider which of the following types of research studies fits best with what you want to learn about your topic. In subsequent chapters, we will use these broad frameworks to help craft your study’s final research question and choose quantitative and qualitative research methods to answer it.

Exploratory research

Researchers conducting exploratory research are typically at the early stages of examining their topics. Exploratory research projects are carried out to test the feasibility of conducting a more extensive study and to figure out the “lay of the land” with respect to the particular topic. Usually, very little prior research has been conducted on this topic. For this reason, a researcher may wish to do some exploratory work to learn what method to use in collecting data, how best to approach research subjects, or even what sorts of questions are reasonable to ask.

Often, student projects begin as exploratory research. Because students don’t know as much about the topic area yet, their working questions can be general and vague. That’s a great place to start! An exploratory question is great for delving into the literature and learning more about your topic. For example, the question “what are common social work interventions for parents who neglect their children?” is a good place to start when looking at articles and textbooks to understand what interventions are commonly used with this population. However, it is important for a student research project to progress beyond exploration unless the topic truly has very little existing research.

In my classes, I often read papers where students say there is not a lot of literature on a topic, but a quick search of library databases shows a deep body of literature on the topic. The skills you develop in subsequent chapters should assist you with finding relevant research, and working with a librarian can definitely help with finding information for your research project. That said, there are a few students each year who pick a topic for which there is in fact little existing research.

Descriptive research

Another purpose of a research project is to describe or define a particular phenomenon. This is called descriptive research. For example, researchers at the Princeton Review conduct descriptive research each year when they set out to provide students and their parents with information about colleges and universities around the United States. They describe the social life at a school, the cost of admission, and student-to-faculty ratios (to name just a few of the categories reported). If our topic were child neglect, we might seek to know the number of people arrested for child neglect in our community and whether they are more likely to have other problems, such as poverty, mental health issues, or substance use.

Social workers often rely on descriptive research to tell them about their service area. Keeping track of the number of parents receiving child neglect interventions, their demographic makeup (e.g., race, sex, age), and length of time in care are excellent examples of descriptive research. On a more macro-level, the Centers for Disease Control provides a remarkable amount of descriptive research on mental and physical health conditions. In fact, descriptive research has many useful applications, and you probably rely on such findings without realizing you are reading descriptive research.

The type of research you are conducting will impact the research question that you ask. Probably the easiest questions to think of are quantitative descriptive questions. For example, “What is the average student debt load of MSW students?” is a descriptive question—and an important one. We aren’t trying to build a causal relationship here. We’re simply trying to describe how much debt MSW students carry. Quantitative descriptive questions like this one are helpful in social work practice as part of community scans, in which human service agencies survey the various needs of the community they serve. If the scan reveals that the community requires more services related to housing, child care, or day treatment for people with disabilities, a nonprofit office can use the community scan to create new programs that meet a defined community need.

Quantitative descriptive questions will often ask for percentage, count the number of instances of a phenomenon, or determine an average. Descriptive questions may only include one variable, such as ours about student debt load, or they may include multiple variables. Because these are descriptive questions, our purpose is not to investigate causal relationships between variables. To do that, we need to use a quantitative explanatory question.

Explanatory research

Lastly, social work researchers often aim to explain why particular phenomena operate in the way that they do. Research that answers “why” questions is referred to as explanatory research. Asking “why” means the researcher is trying to identify cause-and-effect relationships in their topic. For example, explanatory research may try to identify risk and protective factors for parents who neglect their children. Explanatory research may attempt to understand how religious affiliation impacts views on immigration. All explanatory research tries to study cause-and-effect relationships between two or more variables. A specific offshoot of explanatory research that comes up often is evaluation research, which investigates the impact of an intervention, program, or policy on a group of people. Evaluation research is commonly practiced in agency-based social work settings, and later chapters will discusses some of the basics for conducting a program evaluation.

There are numerous examples of explanatory social scientific investigations. For example, Dominique Simons and Sandy Wurtele (2010)[4] sought to understand whether receiving corporal punishment from parents led children to turn to violence in solving their interpersonal conflicts with other children. In their study of 102 families with children between the ages of 3 and 7, the authors found that experiencing frequent spanking did in fact result in children being more likely to accept aggressive problem-solving techniques. Another example of explanatory research can be seen in Robert Faris and Diane Felmlee’s (2011)[5] research study on the connections between popularity and bullying. From their study of 8th, 9th, and 10th graders in nineteen North Carolina schools, they found that aggression increased as adolescents’ popularity increased.[6]

Most studies you read in the academic literature will be quantitative and explanatory. If designed rigorously, study results are generalizable, applicable to larger groups. The editorial board of a journal wants to make sure their content will be useful to as many people as possible, so it’s not surprising that quantitative research dominates the academic literature.

Structurally, quantitative explanatory questions must contain an independent variable, or cause, and dependent variable, or effect. Questions should ask about the relationship between these variables. The standard format I was taught in graduate school for an explanatory quantitative research question is: “What is the relationship between changes in [independent variable] and changes in [dependent variable] for [target population]?” You should play with the wording for your research question, revising that standard format to match what you really want to know about your topic.

Exercises

- Which type of research—exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory—best describes your working question?

- Try writing a question about your topic that fits with each type of research.

Eventually, students in my classroom are guided towards explanatory questions for projects using quantitative research methods and descriptive or exploratory methods for projects using qualitative research methods.

Importance and novelty

Another consideration in starting a research project is whether the question is important enough to answer. For the researcher, answering the question should be important enough to put in the effort and time required to complete a research project. As we discussed in section 2.1, you should choose a topic that is important to you—one you wouldn’t mind learning about for at least a few months, if not a few years. Time is your most precious resource as a student. Make sure you dedicate it to topics and projects you consider genuinely important.

Your research question should also be contribute to the larger expanse of research in that area. For example, if your research question is “does cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) effectively treat depression?” you are a few decades late to be asking that question. Hundreds of scientists have published articles demonstrating its effectiveness in treating depression. However, a student interested in learning more about CBT can still find new areas to research. Perhaps there is a new population—for example, older adults in a nursing home—or a new problem—like mobile phone-based gambling addiction—for which there is little research on the impact of CBT.

Your research project should contribute something new to social science. It should address a gap in what we know and what is written in the literature. This can seem intimidating for students whose projects involve learning a totally new topic. How could I add something new when other researchers have studied this for decades? Trust us, by thoroughly reviewing the existing literature, you can find new and unresolved research questions to answer. Google Scholar’s motto at the bottom of their search page is “stand on the shoulders of giants.” Social science research rests on the work of previous scholars, and builds off of what they discovered to learn more about the social world. Ensure that your question will bring our scientific understanding of your topic to new heights.

Research projects, obviously, do not need to address all aspects of a problem. As social workers, our goal in enacting social justice isn’t to accomplish it all in one semester (or even one lifetime). Our goal is to move the world in the right direction and make small, incremental progress.

Key Takeaways

- Research projects are guided by a working question that develops and changes as you learn more about your topic.

- You should pick a topic for your research proposal that you are interested in, since you will be working with it for several months.

- Social work researchers should identify a target population and understand how their project will impact them.

- Research projects can be exploratory, descriptive, evaluative, or a combination therein. While you are likely still exploring your topic, you may settle on another type of research, particularly if your topic has been previously addressed extensively in the literature.

- Your research project should be important to you, fill a gap or address a controversy in the scientific literature, and make a difference for your target population and broader society.

Exercises

-

Brainstorm at least 4-5 topics of interest to you and pick the one you think is the most promising for a research project.

- Formulate at least one working question to guide your inquiry. It is common for topics to change and develop over the first few weeks of a project, but think of your working question as a place to start. Use the 10 examples we provided in this chapter if you need some help getting started.

- Identify your aim and target population.

- Assess whether your working question is more explanatory, exploratory, or descriptive.

- State why your working question is an important one to answer, keeping in mind that your statement should address the scientific literature, target population, and the social world

2.3 Positionality

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explore your feelings and existing knowledge about the topic

- Assess your Insider or Outsider position

- Contextualize your inquiry in your social location and that of your target population

- Draft a positionality statement

Now that you have an idea of what you might want to study, it’s time to consider what you feel about that topic and your relationship to the people most affected by it. Your motivation for choosing a topic does not have to be objective. Because social work is a value-based profession, scholars often find themselves motivated to conduct research that furthers social justice or fights oppression. Just because you think a policy is wrong or a group is being marginalized, for example, does not mean that your research will be biased. It means you must understand what you feel, why you feel that way, and what would cause you to feel differently about your topic. Openness and honesty are key components of the research process.

Fairness and self-awareness

Start by asking yourself how you feel about your topic. Sometimes the best topics to research are those about which you feel strongly. What better way to stay engaged with your research project than to study something you are passionate about? However, you must be able to accept that people may have a different perspective, and you must represent their viewpoints fairly in the research report you produce. If you feel prepared to accept all findings, even those that may be unflattering or distinct from your personal perspective, then perhaps you should begin your research project by intentionally studying a topic about which you have strong feelings.

Kathleen Blee (2002)[7] has taken this route in her research. Blee studies groups whose racist ideologies may be different than her own. You can listen to her lecture Women in Organized Racism that details some of her findings. Her scientific research is so impactful because she was willing to report her findings and observations honestly, even those contrary to her beliefs and feelings. If you believe that you may have personal difficulty sharing findings with which you disagree, then you may want to study a different topic. Knowing your own hot-button issues demonstrates self-awareness, and there is nothing wrong with avoiding topics that are likely to cause you unnecessary stress.

Social workers often use personal experience as a starting point to identify topics or populations of interest. Personal experience can be a powerful motivator; however, social work researchers should be mindful of their own mental health during the research process. A social worker who has experienced a mental health crisis or traumatic event should approach researching related topics cautiously. There is no need to trigger yourself or jeopardize your mental health for a research project. A while ago, I taught a student who had just experienced domestic violence. She wanted to know about Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy for domestic violence survivors. While the student would surely gain some knowledge about her own potential treatment, they would have to read through many stories and reports about domestic violence as part of the research process. Unless the student’s trauma has been processed in therapy, conducting a research project on this topic may negatively impact the student’s mental health. You do not need to hurt yourself to complete a research project!

Insider vs. outsider perspective

Whether a researcher should be an Insider or Outsider to the communities, cultures, and topics under consideration remains an ongoing debate (e.g., Hammersley, 1993; Weiner et al., 2012). Scientists try to present information accurately and truthfully, and an Insider or Outsider perspective can present benefits and drawbacks. Social work researchers may be Insiders if they have lived experience with a problem or come from the community under study. However, many social workers are outsiders to the topics they study. It is not a requirement to have a specific mental health diagnosis or traumatic life event in order to study it. Both insider and outsider positions are valid, and there are various arguments for the advantages and disadvantages of each position.

Sociologist and philosopher of science, Robert Merton’s summarized it a bit too simply when he said: “Insiders are the members of specified groups and collectives or occupants of specified social statuses: Outsiders are non-members” (Merton, 1972). You are likely familiar with this idea already. For example, it is common for people in recovery from substance use disorders to provide direct services and conduct social science research with clients diagnosed with these disorders. Membership gives Insiders a lived familiarity with and a priori knowledge of the group being researched.

Membership as an Insider our Outsider also related to the social location of the researcher and the target population. The vectors of privilege and oppression social workers are familiar with including gender, race, disability, class, or sexual orientation shape every step the research process. For example, researchers on poverty may miss survival strategies such as selling blood plasma if they are not from this population.

Advantages and disadvantages

By contrast, the Outsider is a person/researcher who does not have any prior intimate knowledge of the group being researched (Griffith, 1998, cited in Mercer, 2007). In its simplest articulation, the Insider perspective essentially questions the ability of Outsider scholars to competently understand the experiences of those inside the culture, while the Outsider perspective questions the ability of the Insider scholar to sufficiently detach themselves from the culture to be able to study it without bias (Kusow, 2003).

For a more extensive discussion, see (Merton, 1972). The main arguments are outlined below. Advantages of an Insider position include:

- (1) easier access to the culture being studied, as the researcher is regarded as being ‘one of us’ (Sanghera & Bjokert 2008),

- (2) the ability to ask more meaningful or insightful questions (due to possession of a priori knowledge),

- (3) the researcher may be more trusted so may secure more honest answers,

- (4) the ability to produce a more truthful, authentic or ‘thick’ description (Geertz, 1973) and understanding of the culture,

- (5) potential disorientation due to ‘culture shock’ is removed or reduced, and

- (6) the researcher is better able to understand the language, including colloquial language, and non-verbal cues.

Disadvantages of an Insider position include:

- (1) the researcher may be inherently and unknowingly biased, or overly sympathetic to the culture,

- (2) they may be too close to and familiar with the culture (a myopic view), or bound by custom and code so that they are unable to raise provocative or taboo questions,

- (3) research participants may assume that because the insider is ‘one of us’ that they possess more or better insider knowledge than they do, (which they may not) and that their understandings are the same (which they may not be). Therefore information which should be ‘obvious’ to the insider, may not be articulated or explained,

- (4) an inability to bring an external perspective to the process,

- (5) ‘dumb’ questions which an outsider may legitimately ask, may not be able to be asked (Naaek et al. 2010), and

- (6) respondents may be less willing to reveal sensitive information than they would be to an outsider who they will have no future contact with.

Multiple dimensions of belonging

Each position has both advantages and disadvantages, which take on slightly different weights depending on the specific circumstances and the purpose of the research. The insider and outsider roles are essentially products of the particular situation in which research takes place (Kusow, 2003). As such, they are both researcher and context-specific, with no clearly -cut boundaries. And as such may not be a divided binary (Mullings, 1999, Chacko, 2004). Researchers may straddle both positions; they may be simultaneously and insider and an outsider (Mohammed, 2001). Mercer (2007 p.1) suggests that the insider/outsider dichotomy is, in reality, a continuum with multiple dimensions and that all researchers constantly move back and forth along several axes, depending upon time, location, participants, and topic.

For example, a mature female Saudi Ph.D. student studying social work may be an insider to the topic of student mental health. However, as a doctoral student, she is an outsider to undergraduates. She may be regarded as being an insider by Saudi students, but an outsider by students from other countries; an insider to female students, but an outsider to male students; an insider to Muslim students, an outsider to Christian students; an insider to mature students, an outsider to younger students, and so on. Combine these with the many other insider-outsider positions, and it soon becomes clear that it is rarely a case of simply being an insider or outsider.

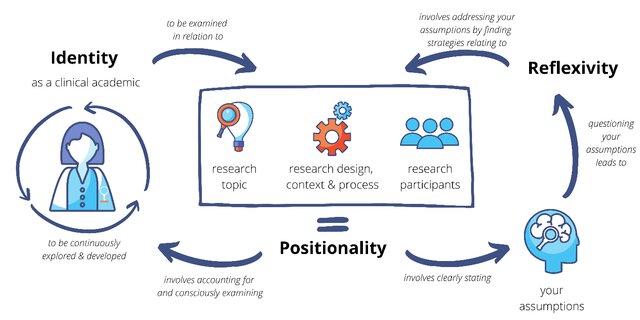

Positionality

Rather than declaring yourself an Insider or Outsider, it is helpful to understand several positions in reference to both (a) the communities and topics in the working question and (b) the researchers’ and communities’ social locations. The term positionality describes the researcher’s assumptions about social science and reality, their views on the research topic, and the relevant social and political context (Foote & Bartell 2011, Savin-Baden & Major, 2013 and Rowe, 2014). Researchers are part of the social world they are researching and that this world has already been interpreted by existing social actors. Positionality implies that the social-historical-political location of a researcher influences their orientations, i.e., that they are not separate from the social processes they study.

It is essential for new researchers to acknowledge that their positionality is unique to them and that it can impact all aspects and stages of the research process. As Foote and Bartell (2011, p.46) identify “The positionality that researchers bring to their work, and the personal experiences through which positionality is shaped, may influence what researchers may bring to research encounters, their choice of processes, and their interpretation of outcomes.” Positionality, therefore, can be seen to affect the totality of the research process.

Novice researchers should realize that, right from the very start of the research process, that their positionality will affect their research and will impact their understanding, interpretation, and belief/disbelief of other researcher’s findings. It will also influence how you design your own study

Savin-Baden & Major (2013) ask researchers to identify the (a) beliefs, (b) values, and (c) identities that are relevant to each component of the research process including:

- The topics in the working question

- The communities, clients, and people in your working question

- The research process itself, and how you will be influenced by the research process.

Investigating and clarifying one’s positionality takes time. New researchers should recognize that exploring their positionality can take considerable time and much ‘soul searching’. It is not a process that can be rushed, and like crafting a good research question. Researchers must engage in constant self-reflection to identify, construct, critique, and articulate their positionality. It is important for new researchers to note here that their positionality not only shapes their work but influences their interpretation, understanding, and, ultimately, their belief in the truthfulness and validity of other’s research that they read or are exposed to. It also influences the importance given to, the extent of belief in, and their understanding of the concept of positionality.

Positionality statements

Rather than trying to eliminate the effect of their positionality, researchers should acknowledge and disclose their selves in their work, aiming to understand their influence on and in the research process. Positionality requires that both acknowledgment and allowance are made by the researcher to locate their views, values, and beliefs about the research topic, process, and target population.

Positionality is often formally expressed in research papers, masters-level dissertations, and doctoral theses via a positionality statement, essentially an explanation of how the researcher developed and how they became the researcher they are then. For most researchers, this will necessarily be a fluid statement that changes as they develop both through conducting a specific research project and throughout their research career.

A strong positionality statement will typically include:

- A description of the researcher’s lenses (such as their philosophical, personal, theoretical beliefs and perspective through which they view the research process),

- Potential influences on the research (such as age, political beliefs, social class, race, ethnicity, gender, religious beliefs, previous career),

- The researcher’s chosen or pre-determined position about the target population and the specific participants included in the data collection

- The research-project context and an explanation as to how, where, when and in what way these might, may, or have, influenced the research process (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013).

Producing a good positionality statement takes time, considerable thought, and critical reflection. Through exploring their positionality, the novice researcher increasingly becomes aware of areas where they may have potential bias and, over time, are better able to identify these so that they may then take account of them.

Reflecting on one’s positionality should reduce bias and motivated reasoning in scientific inquiry (Rowe, 2014). However, no matter how reflective a researcher is, they can never objectively describe something as it truly is. There will always still be some form of bias. Ormston and colleagues (2014) suggest that researchers should aim to achieve ‘empathetic neutrality,” “strive to avoid obvious, conscious, or systematic bias and to be as neutral as possible in the collection, interpretation, and presentation of data…[while recognizing that] this aspiration can never be fully attained – all research will be influenced by the researcher and there is no completely ‘neutral’ or ‘objective’ knowledge” (p. ?).

Key Takeaways

- Investigate your own feelings and thoughts about a topic, and make sure you can be objective and fair in your investigation.

- Researchers can be insiders or outsiders to the topics and populations under study, influencing the research process.

- Positionality statements are tools for researchers to account for their values, identities, and experiences relevant to the working question.

Exercises

- Draft a brief positionality statement based on your feelings about the topic.

- Include your insider/outsider position as well as relevant aspects of your social location, including culture, race, gender, age, disability, national origin, and other factors.

- Keep the document open and consider using it as a diary as your assumptions and ideas about the topic deepen as a result of scientific inquiry.

2.4 First thoughts and information needs

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify a a need for information knowledge about a subject area

- Identify a working question and define it using simple terminology

- Articulate current knowledge on a topic

- Recognize a need for information and data to achieve a specific end and define limits to the information need

- Identify the key concepts relevant to your research question and inquiry into the literature

Now that you have a sense of your relevant beliefs, identities, and experiences, let’s consider what you know already, where you learned it, and what you need to know next to inform your inquiry.

What do you already know?

Part of identifying your own information need is giving yourself credit for what you already know about your topic. It can be helpful to visualize your information need using a chart. Construct a chart using the following format to list whatever you already know about the topic.

A simple tracking chart can be seen in Figure 2.3. In the first column, list what you know about your topic. In the second column, briefly explain how you know this (heard it from the professor, read it in the textbook, saw it on a blog, etc.). In the last column, rate your confidence in that knowledge. Are you 100% sure of this bit of knowledge, or did you just hear it somewhere and assume it was right?

When you’ve looked at everything you think you know about the topic and why, step back and look at the chart as a whole. How much do you know about the topic, and how confident are you about it? You may be surprised at how little or how much you already know, but either way you will be aware of your own background on the topic. This self-awareness is key to becoming more information literate.

This exercise gives you a simple way to gauge your starting point, and may help you identify specific gaps in your knowledge of your topic that you will need to fill as you proceed with your research. It can also be useful to revisit the chart as you work on your project to see how far you’ve progressed, as well as to double check that you haven’t forgotten an area of weakness.

What do you need to learn?

Once you’ve clearly stated what you do know, it should be easier to state what you don’t know. Keep in mind that you are not attempting to state everything you don’t know. You are only stating what you don’t know in terms of your current information need. This is where you define the limits of what you are searching for. These limits enable you to meet both size requirements and time deadlines for a project. If you state them clearly, they can help to keep you on track as you proceed with your research. You can learn more about this in the Scope chapter of this book.

One useful way to keep your research on track is with a “KWHL” chart. This type of chart enables you to state both what you know and what you want to know, as well as providing space where you can track your planning, searching and evaluation progress. For now, just fill out the first column, but start thinking about the gaps in your knowledge and how they might inform your research questions. You will learn more about developing these questions and the research activities that follow from them as you work through this book.

Revising your working question

Once you have identified your own need for knowledge, investigated the existing information on the topic, and set some limits on your research based on your current information need, write out your working question. You’ll find that it’s not uncommon to revise your question several times in the course of a research project. As you become more and more knowledgeable about the topic, you will be able to state your ideas more clearly and precisely, until they almost perfectly reflect the information you have found.

Exercises

- State your working question.

- Write your proposed answer to that question…as best you know right now.

- It doesn’t have to be perfect at this point, but based on your current understanding of your topic and what you expect or hope to find is the answer to the question you asked.

Look at your question and proposed answer, and make a list of the terms common to both lists (excluding “the,” “and,” “a,” etc.). These common terms are likely the important concepts that you will need to research to inform your search for information. They may be the most useful search terms overall or they may only be a starting point.

If none of the terms from your question and answer lists overlap at all, you might want to take a closer look. If your question and answer do not match, you may have arrived at your first opportunity for revision. For example, f your question asks about self-esteem and your hypothesis talks about self-concept, the answers you seek will not address your working question.

- Does your question really ask what you’re trying to find out?

- Does your proposed answer really answer that question?

You may find that you need to change one or both, or to add something to one or both to really get at what you’re interested in. This is part of the process, and you will likely discover that as you gather more information about your topic, you will find other ways that you want to change your question or thesis to align with the facts, even if they are different from what you hoped.

Developing a working question can be more difficult than it seems. Your initial questions may be too broad or too narrow. You may not be familiar with specialized terminology used in the field you are researching. You may not know if your question is worth investigating at all.

These problems can often be solved by a preliminary investigation of scholarly information on the topic. Gaining a general understanding of the information environment helps you to situate your information need in the relevant context and can also make you aware of possible alternative directions for your research. On a more practical note, however, reading through some of the existing information can also provide you with commonly used terminology, which you can then use to state your own research question, as well as in searches for additional information.

Don’t try to reinvent the wheel, but rely on the experts who have laid the groundwork for you to build upon. Find good, argumentative writing from scholars, experts, and people with lived experience that you find insightful.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers continually revise their working question and the answers they are considering throughout the literature search process.

- Your existing knowledge on a topic is a resource you can rely upon, but you will be required as social work practitioners to show evidence that what you say is scientifically true.

- As you learn more about your topic (theories, key terms, history, etc.), you should revise your working question and the answers you are considering to it.

2.5 Evaluating internet resources

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Apply the SIFT technique to find better coverage of scientific information and current events.

When first learning about a new topic, a natural first place to look is an internet search engine (e.g., Google, Bing, or DuckDuckGo). Before diving into the academic literature (which we will do in the next chapter), let’s explore how to use research methods to find scientific information that is intended for non-expert audiences. Take some time to learn the basics of your topic before you dive into more advanced literature, which may present a more nuanced (or jargon-filled and confusing) study of the topic. Generally, scholarly literature is specialized, in that it does not try to provide a broad overview of a topic for a non-expert audience. When you are looking at journal articles, you are looking at literature intended for other scientists and researchers.

While you can be assured that articles in reputable journals have passed peer review, that does not always mean they contain accurate information. Articles are often debated on social media or in journalistic outlets. For example, here is a news story debunking a journal article which erroneously found Safe Consumption Sites for people who use drugs were moderately associated with crime increases. After multiple scholars evaluated the article’s data, they realized there were flaws in the design and the conclusions were not supported, which led the journal to retract the article.

If your literature search contains sources other than academic journal articles (and almost all of them do), you’ll need to do a bit more work to assess whether the source is reputable enough to include in your review. Let’s say you find a report from a Google Scholar search or a Bing search. Without peer review or a journal’s approval, how do you know the information you are reading is any good?

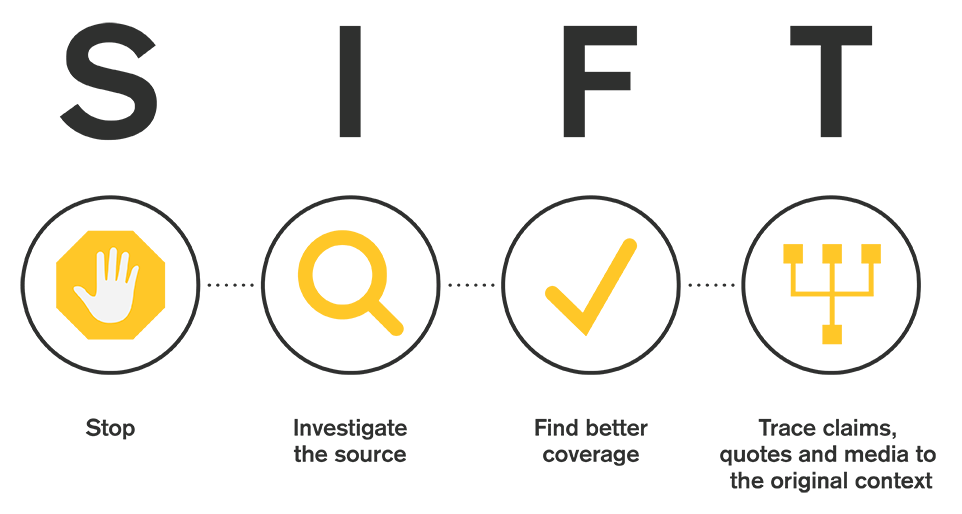

The SIFT method

Mike Caulfield, Washington State University digital literacy expert, has helpfully condensed key fact-checking strategies into a short list of four moves, or things to do to quickly make a decision about whether or not a source is worthy of your attention. It is referred to as the “SIFT” method, and it stands for Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims claims, quotes, and media to the original context.

Stop

Stop

When you initially encounter a source of information and start to read it—stop. Ask yourself whether you know and trust the author, publisher, publication, or website. If you don’t, use the other fact-checking moves that follow, to get a better sense of what you’re looking at. In other words, don’t read, share, or use the source in your research until you know what it is, and you can verify it is reliable.

This is a particularly important step, considering what we know about the attention economy—social media, news organizations, and other digital platforms purposely promote sensational, divisive, and outrage-inducing content that emotionally hijacks our attention in order to keep us “engaged” with their sites (clicking, liking, commenting, sharing). Stop and check your emotions before engaging! What about this website is driving your engagement?

Investigate the sources

You don’t have to do a three-hour investigation into a source to determine its truth. But if you’re reading a piece on economics, and the author is a Nobel prize-winning economist, that would be useful information. Likewise, if you’re watching a video on the many benefits of milk consumption, you would want to be aware if the video was produced by the dairy industry. This doesn’t mean the Nobel economist will always be right and that the dairy industry can’t ever be trusted. But knowing the expertise and agenda of the person who created the source is crucial to your interpretation of the information provided.

When investigating a source, fact-checkers read “laterally” across many websites, rather than digging deep (reading “vertically”) into the one source they are evaluating. That is, they don’t spend much time on the source itself, but instead they quickly get off the page and see what others have said about the source. Indeed, one study cited in the video below found that academic historians are actually less able to tell the difference between reputable and bogus internet sources because they do not read laterally but instead check references and credentials. Those are certainly a good idea to check when reading a source in detail, but fact checkers instead ask what other sources on the web say about it rather than what the source says about itself. They open up many tabs in their browser, piecing together different bits of information from across the web to get a better picture of the source they’re investigating. Not only is this faster, but it harnesses the collected knowledge of the web to more accurately determine whether a source is reputable or not.

We recommend watching this short video [2:44] for a demonstration of how to investigate online sources. Pay particular attention to how Wikipedia can be used to quickly get useful information about publications, organizations, and authors. Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Find better coverage

What if the source you find is low-quality, or you can’t determine if it is reliable or not? Perhaps you don’t really care about the source—you care about the claim that source is making. You want to know if it is true or false. You want to know if it represents a consensus viewpoint, or if it is the subject of much disagreement. A common example of this is a meme you might encounter on social media. The random person or group who posted the meme may be less important than the quote or claim the meme makes.

Your best strategy in this case might actually be to find a better source altogether, to look for other coverage that includes trusted reporting or analysis on that same claim. Rather than relying on the source that you initially found, you can trade up for a higher quality source. The point is that you’re not wedded to using that initial source. We have the internet! You can go out and find a better source, and invest your time there.

We recommend watching this short video [4:10] that demonstrates how to find better coverage and notes how fact-checkers build a library of trusted sources they can rely on to provide better coverage. Note: Turn on closed captions with the “CC” button or use the text transcript if you prefer to read.

Trace claims, quotes, and media to the original context

Much of what we find on the internet has been stripped of context. Maybe there’s a video of a fight between two people with Person A as the aggressor. But what happened before that? What was clipped out of the video and what stayed in? Maybe there’s a picture that seems real but the caption could be misleading. Maybe a claim is made about a new medical treatment based on a research finding—but you’re not certain if the cited research paper actually said that. The people who re-report these stories either get things wrong by mistake, or, in some cases, they are intentionally misleading us.

In these cases you will want to trace the claim, quote, or media back to the source, so you can see it in its original context and get a sense of whether the version you saw was accurately presented. We will talk about this more in Chapter 3 when we distinguish between primary sources and secondary sources. Secondary and tertiary sources are great for getting started with a topic, but researchers want to rely on the most highly informed source to give us information about a topic. If you see a news article about a research study, look for the journal article written by the researchers who performed the study as citations for your paper rather than a journalist who is unaffiliated with the project.

We recommend watching this short video [1:33] that discusses re-reporting vs. original reporting and demonstrates a quick tip: going “upstream” to find the original reporting source. Researchers must follow the thread of information from where they first read it to where it originated in order to understand its truth and value. Social workers who fail to check their sources can spread misinformation within our practice context or come to ill-informed conclusions that hurt clients or communities.

Once you have limited your search to trustworthy sources, ask yourself the following questions when evaluating which of these sources to read:

- Does this source help me answer my working question?

- Does this source help me revise and focus my working question?

- Does this source help me address what my professor expects in a literature review?

- Is this the best source I can find? Is this a primary or secondary source?

- What is the original context of this information?

- Is there controversy surrounding this source?

- Are the publisher and author reputable and unbiased?

Reflect and plan for the future

As you look search the literature, you will learn more about your topic area. You will learn new concepts that become new keywords in new queries. You will continue to come up with search queries and download articles throughout the research process. While we present this material at the beginning of the textbook, that is a bit misleading. You will return to search the literature often during the research process. As such, it is important to keep notes about what you did at each stage. I usually keep a “working notes” document in the same folder as the PDFs of articles I download. I can write down which categories different articles fall into (e.g., theoretical articles, empirical articles), reflect on how my question may need to change, or highlight important unresolved questions or gaps revealed in my search.

Creating and refining your working question will help you identify the key concepts you study will address. Once you identify those concepts, you’ll need to decide how to define them and how to measure them when it comes time to collect your data. As you are reading articles, note how other researchers who study your topic define concepts theoretically in the introduction and measure them in their methods section. Tuck these notes away for the future, when you will have to define and measure these concepts.

You need to be able to speak intelligently about the target population you want to study, so finding literature about their strengths, challenges, and how they have been impacted by historical and cultural oppression is a good idea. Last, but certainly not least, you should consider any potential ethical concerns that could arise during the course of carrying out your research project. These concerns might come up during your data collection, but they may also arise when you get to the point of analyzing data or disseminating results.

Decisions about the various research components do not necessarily occur in sequential order. For example, you may have to think about potential ethical concerns before changing your working question. In summary, the following list shows some of the major components you’ll need to consider as you design your research project. Make sure you have information that will inform how you think about each component.

- Research question

- Literature review

- Theories and causal relationships

- Unit of analysis and unit of observation

- Key concepts (conceptual definitions and operational definitions)

- Method of data collection

- Research participants (sample and population)

- Ethical concerns

Carve some time out each week during the beginning of the research process to revisit your working question. As you write notes on the articles you find, reflect on how that knowledge would impact your working question and the purpose of your research. You still have some time to figure it out. We’ll work on turning your working question into a full-fledged research question in Parts 2 and 3 of the textbook.

Key Takeaways

- Research requires fact-checking. The SIFT technique is an easy approach to critically investigating internet resources about your topic.

- Investigate the source of the information you find on the web and look for better coverage.

- Search for internet resources that help you address your working question and write your research proposal.

Exercises

- Look at your professor’s prompt for a literature review and sketch out how you might answer those questions using your present level of knowledge. Search for sources that support or challenge what you think is true about your topic.

- Find a news article reporting about topics similar to your working question. Identify whether it is a primary or secondary source. If it is a secondary source, trace any claims to their primary sources. Provide the URLs.

- Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662 ↵

- Healy, K. (2001). Participatory action research and social work: A critical appraisal. International Social Work, 44, 93-105. ↵

- Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research, 1, 7-24.; Reason, P. (1994). Participation in human inquiry. London, UK: Sage. ↵

- Simons, D. A., & Wurtele, S. K. (2010). Relationships between parents’ use of corporal punishment and their children’s endorsement of spanking and hitting other children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 639–646. ↵

- Faris, R., & Felmlee, D. (2011). Status struggles: Network centrality and gender segregation in same- and cross-gender aggression. American Sociological Review, 76, 48–73. The study has also been covered by several media outlets: Pappas, S. (2011). Popularity increases aggression in kids, study finds. Retrieved from: http://www.livescience.com/11737-popularity-increases-aggression-kids-study-finds.html ↵

- This pattern was found until adolescents reached the top 2% in the popularity ranks. After that, aggression declined. ↵

- Blee, K. (2002). Inside organized racism: Women and men of the hate movement. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; Blee, K. (1991). Women of the Klan: Racism and gender in the 1920s. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ↵

a document produced by researchers that reviews the literature relevant to their topic and describes the methods they will use to conduct their study

a nonlinear process in which the original product is revised over and over again to improve it

what a researcher hopes to accomplish with their study

the group of people whose needs your study addresses

conducted during the early stages of a project, usually when a researcher wants to test the feasibility of conducting a more extensive study or if the topic has not been studied in the past

research that describes or defines a particular phenomenon

explains why particular phenomena work in the way that they do; answers “why” questions

“a logical grouping of attributes that can be observed and measured and is expected to vary from person to person in a population” (Gillespie & Wagner, 2018, p. 9)

research that evaluates the outcomes of a policy or program

describes an individual’s world view and the position they adopt about a research task and its social and political context

in a literature review, a source that describes primary data collected and analyzed by the author, rather than only reviewing what other researchers have found

interpret, discuss, and summarize primary sources

entity that a researcher wants to say something about at the end of her study (individual, group, or organization)

the entities that a researcher actually observes, measures, or collects in the course of trying to learn something about her unit of analysis (individuals, groups, or organizations)

a network of linked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon

The concrete and specific defintion of something in terms of the operations by which observations can be categorized.