25 21. Qualitative research dissemination

Matthew DeCarlo

Chapter Outline

- Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness (8 minute read)

- Critical considerations (5 minute read)

- Informing your dissemination plan (11 minute read)

- Final product taking shape (10 minute read)

Content warning: Examples in this chapter contain references to research as a potential tool to stigmatize or oppress vulnerable groups, mistreatment and inequalities experienced by Native American tribes, sibling relationships, caregiving, child welfare, criminal justice and recidivism, first generation college students, Covid-19, school culture and race, health (in)equity, physical and sensory abilities, and transgender youth.

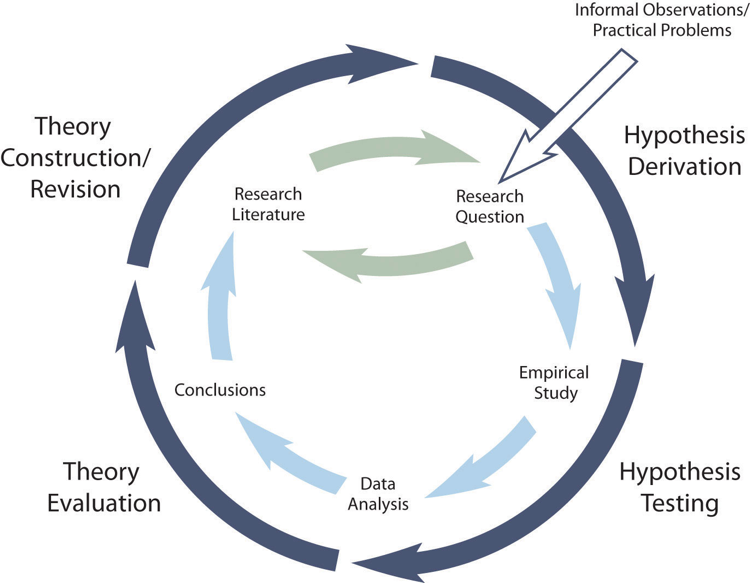

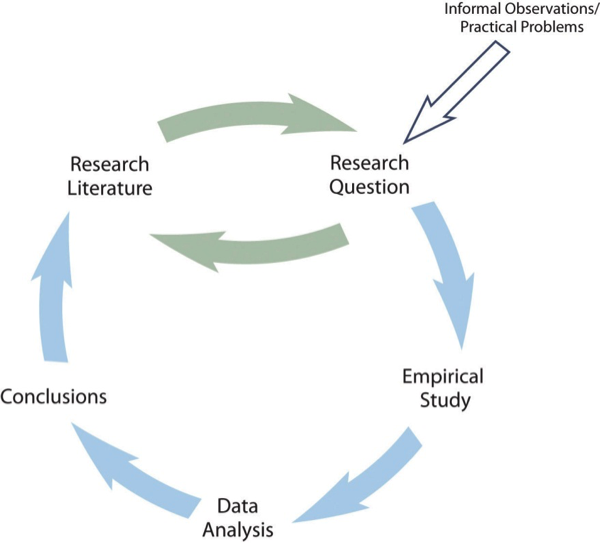

Your sweat and hard work has paid off! You’ve planned your study, collected your data, and completed your analysis. But alas, no rest for the weary student researcher. Now you need to share your findings. As researchers, we generally have some ideas where and with whom we desire to share our findings, but these plans may evolve and change during our research process. Communicating our findings with a broader audience is a critical step in the research process, so make sure not to treat this like an afterthought. Remember, research is about making a contribution to collective knowledge-building in the area of study that you are interested in. Indeed, research is of no value if there is no audience to receive it. You worked hard…get those findings out there!

In planning for this phase of research, we can consider a variety of methods for sharing our study findings. Among other options, we may choose to write our findings up as an article in a professional journal, provide a report to an organization, give testimony to a legislative group, or create a presentation for a community event. We will explore these options in a bit more detail below in section 21.4 where we talk more about different types of qualitative research products. We also want to think about our intended audience.

Exercises

For your research, answer these two key questions as you are planning for dissemination:

- Who are you targeting to communicate your findings to? In other words, who needs to hear the results of your study?

- What do you hope your audience will take away after learning about your study?

Of course, we can’t know how our findings will be received, but we will want to work to anticipate what expectations our target audience might have and use this information to tailor our message in a way that is clear, thorough and consistent with our data (keep it honest!). We will further discuss different audiences you might want to reach with your research and a few considerations for each type of audience that may shape your dissemination plan. Before we tackle these sections, we are going to take some time to think through ethical and critical considerations that should be at the forefront of your mind as you plan for the dissemination of your research. Remember, your research is NOT a static, inanimate object. It is a reflection of your participants. Furthermore, others will review, interpret and potentially form opinions based on your research Your research has real implications for individuals, groups, communities, agencies, programs, etc.

21.1 Ethical responsibility and cultural respectfulness

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify key ethical considerations in developing their qualitative research dissemination plan

- Conceptualize how research dissemination may impact diverse groups, both presently and into the future

Have you ever been misrepresented or portrayed in a negative light? It doesn’t feel good. It especially doesn’t feel good when the person portraying us has power, control and influence. While you might not feel powerful, research can be a powerful tool, and can be used and abused for many ends. Once research is out in the world, it is largely out of our control, so we need to approach dissemination with care. Be thoughtful about how you represent your work and take time to think through the potential implications it may have, both intended and unintended, for the people it represents.

As alluded to in the paragraph above, research comes with hefty responsibilities. You aren’t off the hook if you are conducting quantitative research. While quantitative research deals with numbers, these numbers still represent people and their relationships to social problems. However, with qualitative research, we are often dealing with a smaller sample and trying to learn more from them. As such, our job often carries additional weight as we think about how we will represent our findings and the people they reflect. Furthermore, we probably hope that our research has an impact; that in some way, it leads to change around some issue. This is especially true as social work researchers. Our research often deals with oppressed groups, social problems, and inequality. However, it’s hard to predict the implications that our research may have. This suggests that we need to be especially thoughtful about how we present our research to others.

Two of the core values of social work involve respecting the inherent dignity and worth of each person, practicing with integrity, and behaving in a trustworthy manner.[1] As social work researchers, to uphold these values, we need to consider how we are representing the people we are researching. Our work needs to honestly and accurately reflect our findings, but it also needs to be sensitive and respectful to the people it represents. In Chapter 6 we discussed research ethics and introduced the concept of beneficence or the idea that research needs to support the welfare of participants. Beneficence is particularly important as we think about our findings becoming public and how the public will receive, interpret and use this information. Thus, both as social workers and researchers, we need to be conscientious of how dissemination of our findings takes place.

Exercises

As you think about the people in your sample and the communities or groups to which they belong, consider some of these questions:

- How are participants being portrayed in my research?

- What characteristics or findings are being shared or highlighted in my research that may directly or indirectly be associated with participants?

- Have the groups that I am researching been stigmatized, stereotyped, and/or misrepresented in the past? If so, how does my research potentially reinforce or challenge these representations?

- How might my research be perceived or interpreted by members of the community or group it represents?

- In what ways does my research honor the dignity and worth of participants?

Qualitative research often has a voyeuristic quality to it, as we are seeking a window into participants’ lives by exploring their experiences, beliefs, and values. As qualitative researchers, we have a role as stewards or caretakers of data. We need to be mindful of how data are gathered, maintained, and most germane to our conversation here, how data are used. We need to craft research products that honor and respect individual participants (micro), our collective sample as a whole (meso), and the communities that our research may represent (macro).

As we prepare to disseminate our findings, our ethical responsibilities as researchers also involve honoring the commitments we have made during the research process. We need to think back to our early phases of the research process, including our initial conversations with research partners and other stakeholders who helped us to coordinate our research activities. If we made any promises along the way about how the findings would be presented or used, we need to uphold them here. Additionally, we need to abide by what we committed to in our informed consent. Part of our informed consent involves letting participants know how findings may be used. We need to present our findings according to these commitments. We of course also have a commitment to represent our research honestly.

As an extension of our ethical responsibilities as researchers, we need to consider the impact that our findings may have, as well as our need to be socially conscientious researchers. As scouts, we were taught to leave our campsite in a better state than when we arrived. I think it is helpful to think of research in these terms. Think about the group(s) that may be represented by your research; what impact might your findings have for the lives of members of this group? Will it leave their lives in a better state than before you conducted your research? As a responsible researcher, you need to be thoughtful, aware and realistic about how your research findings might be interpreted and used by others. As social workers, while we hope that findings will be used to improve the lives of our clients, we can’t ignore that findings can also be used to further oppress or stigmatize vulnerable groups; research is not apolitical and we should not be naive about this. It is worth mentioning the concept of sustainable research here. Sustainable research involves conducting research projects that have a long-term, sustainable impact for the social groups we work with. As researchers, this means that we need to actively plan for how our research will continue to benefit the communities we work with into the future. This can be supported by staying involved with these communities, routinely checking-in and seeking input from community members, and making sure to share our findings in ways that community members can access, understand, and utilize them. Nate Olson provides a very inspiring Ted Talk about the importance of building resilient communities. As you consider your research project, think about it in these terms.

Key Takeaways

- As you think about how best to share your qualitative findings, remember that these findings represent people. As such, we have a responsibility as social work researchers to ensure that our findings are presented in honest, respectful, and culturally sensitive ways.

- Since this phase of research deals with how we are going to share our findings with the public, we need to actively consider the potential implications of our research and how it may be interpreted and used.

Exercises

- Is your work, in some way, helping to contribute to a resilient and sustainable community? It may not be a big tangible project as described in Olson’s Ted Talk, but is it providing a resource for change and growth to a group of people, either directly or indirectly? Does it promote sustainability amongst the social networks that might be impacted by the research you are conducting?

21.2 Critical considerations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify how issues of power and control are present in the dissemination of qualitative research findings

- Begin to examine and account for their own role in the qualitative research process, and address this in their findings

This is the part of our research that is shared with the public and because of this, issues like reciprocity, ownership, and transparency are relevant. We need to think about who will have access to the tangible products of our research and how that research will get used. As researchers, we likely benefit directly from research products; perhaps it helps us to advance our career, obtain a good grade, or secure funding. Our research participants often benefit indirectly by advancing knowledge about a topic that may be relevant or important to them, but often don’t experience the same direct tangible benefits that we do. However, a participatory perspective challenges us to involve community members from the outset in discussions about what changes would be most meaningful to their communities and what research products would be most helpful in accomplishing those changes. This is especially important as it relates to the role of research as a tool to support empowerment.

Ownership of research products is also important as an issue of power and control. We will discuss a range of venues for presenting your qualitative research, some of which are more amenable to shared ownership than others. For instance, if you are publishing your findings in an academic journal, you will need to sign an agreement with that publisher about how the information in that article can be used and who has access to it. Similarly, if you are presenting findings at a national conference, travel and other conference-related expenses and requirements may make access to these research products prohibitive. In these instances, the researcher and the organization(s) they negotiate with (e.g. the publishing company, the conference organizing body) share control. However, disseminating qualitative findings in a public space, public record, or community-owned resource means that more equitable ownership might be negotiated. An equitable or reciprocal arrangement might not always be able to be reached, however. Transparency about who owns the products of research is important if you are working with community partners. To support this, establishing a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) or Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) early in the research process is important. This document should clearly articulate roles, responsibilities, and a number of other details, such as ownership of research products between the researcher and the partnering group(s).

Resources for learning more about MOUs and MOAs

Center for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas. (n.d.). Section 9. Understanding and writing contracts and memoranda of agreement.

Collaborative Center for Health Equity, University of Wisconson Madison. (n.d.). Standard agreement for research with community organizations.

Office of Research, UC Davis. (n.d.). Research MOUs.

Office of Research, The University of Texas at Dallas. (n.d.). Types of agreements.

In our discussion about qualitative research, we have also frequently identified the need for the qualitative researcher to account for their role throughout the research process. Part of this accounting can specifically apply to qualitative research products. This is our opportunity to demonstrate to our audience that we have been reflective throughout the course of the study and how this has influenced the work we did. Some qualitative research studies include a positionality statement within the final product. This is often toward the beginning of the report or the presentation and includes information about the researcher(s)’s identity and worldview, particularly details relevant to the topic being studied. This can include why you are invested in the study, what experiences have shaped how you have come to think about the topic, and any positions or assumptions you make with respect to the topic. This is another way to encourage transparency. It can also be a means of relegating or at least acknowledging some of our power in the research process, as it can provide one modest way for us, as the researcher, to be a bit more exposed or vulnerable, although this is a far cry from making the risks of research equitable between the researcher and the researched. However, the positionality statement can be a place to integrate our identities, who we are as an individual, a researcher, and a social work practitioner. Granted, for some of us that might be volumes, but we need to condense this down to a brief but informative statement—don’t let it eclipse the research! It should just be enough to inform the audience and allow them to draw their own conclusions about who is telling the story of this research and how well they can be trusted. This student provides a helpful discussion of the positionality statement that she developed for her study. Reviewing your reflexive journal (discussed in Chapter 20 as a tool to enhance qualitative rigor) can help in identifying underlying assumptions and positions you might have grounded in your reactions throughout the research process. These insights can be integrated into your positionality statement. Please take a few minutes to watch this informative video of a student further explaining what a positionality statement is and providing a good example of one.

Key Takeaways

- The products of qualitative research often benefit the researcher disproportionately when compared to research participants or the communities they represent. Whenever possible, we can seek out ways to disseminate research in ways that addresses this imbalance and supports more tangible and direct benefits to community members.

- Openly positioning ourselves in our dissemination plans can be an important way for qualitative researchers to be transparent and account for our role.

21.3 Informing your dissemination plan

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Appraise important dimensions of planning that will inform their research dissemination plan, including: audience, purpose, context and content

- Apply this appraisal to key decisions they will need to make when designing their qualitative research product(s)

This section will offer you a general overview of points to consider as you form the dissemination plan for your research. We will start with considerations regarding your audience, then turn our attention to the purpose of your research, and finally consider the importance of attending to both content and context as you plan for your final research product(s).

Audience

Perhaps the most important consideration you have as you plan how to present your work is your audience. Research is a product that is meant to be consumed, and because of this, we need to be conscious of our consumers. We will speak more extensively about knowing your audience in Chapter 24, devoted to both sharing and consuming research. Regardless of who your audience is (e.g. community members, classmates, research colleagues, practicing social workers, state legislator), there will be common elements that will be important to convey. While the way you present them will vary greatly according to who is listening, Table 21.1 offers a brief review of the elements that you will want your audience to leave with.

| Element | Purpose |

| Aim | What did my research aim to accomplish and why is it important |

| Process | How did I go about conducting my research and what did I do to ensure quality |

| Concepts | What are the main ideas that someone needs to know to make sense of my topic and how are they integrated into my research plan |

| Findings | What were my results and under what circumstances are they valid |

| Connection | How are my findings connected to what else we know about this topic and why are they important |

Once we determine who our audience is, we can further tailor our dissemination plan to that specific group. Of course, we may be presenting our findings in more than one venue, and in that case, we will have multiple plans that will meet the needs of each specific audience.

It’s a good idea to pitch your plan first. However you plan to present your findings, you will want to have someone preview before you share with a wider audience. Ideally, whoever previews will be a person from your target audience or at least someone who knows them well. Getting feedback can go a long way in helping us with the clarity with which we convey our ideas and the impact they have on our audience. This might involve giving a practice speech, having someone review your article or report, or practice discussing your research one-on-one, as you would with a poster presentation. Let’s talk about some specific audiences that you may be targeting and their unique needs or expectations.

Below I will go through some brief considerations for each of these different audiences. I have tried to focus this discussion on elements that are relevant specific to qualitative studies since we do revisit this topic in Chapter 24.

Research community

When presenting your findings to an academic audience or other research-related community, it is probably safe to a make a few assumptions. This audience is likely to have a general understanding of the research process and what it entails. For this reason, you will have to do less explaining of research-related terms and concepts. However, compared to other audiences, you will probably have to provide a bit more detail about what steps you took in your research process, especially as they relate to qualitative rigor, because this group will want to know about how your research was carried out and how you arrived at your decisions throughout the research process. Additionally, you will want to make a clear connection between which qualitative design you chose and your research question; a methodological justification. Researchers will also want to have a good idea about how your study fits within the wider body of scientific knowledge that it is related to and what future studies you feel are needed based on your findings. You are likely to encounter this audience if you are disseminating through a peer-reviewed journal article, presenting at a research conference, or giving an invited talk in an academic setting.

Professional community

We often find ourselves presenting our research to other professionals, such as social workers in the field. While this group may have some working knowledge of research, they are likely to be much more focused on how your research is related to the work they do and the clients they serve. While you will need to convey your design accurately, this audience is most likely to be invested in what you learned and what it means (especially for practice). You will want to set the stage for the discussion by doing a good job expressing your connection to and passion for the topic (a positionality statement might be particularly helpful here), what we know about the issue, and why it is important to their professional lives. You will want to give good contextual information for your qualitative findings so that practitioners can know if these findings might apply to people they work with. Also, as since social work practitioners generally place emphasis on person-centered practice, hearing the direct words of participants (quotes) whenever possible, is likely to be impactful as we present qualitative results. Where academics and researchers will want to know about implications for future research, professionals will want to know about implications for how this information could help transform services in the future or understand the clients they serve.

Lay community

The lay community are people who don’t necessarily have specialized training or knowledge of the subject, but may be interested or invested for some other reason; perhaps the issue you are studying affects them or a loved one. Since this is the general public, you should expect to spend the most time explaining scientific knowledge and research processes and terminology in accessible terms. Furthermore, you will want to invest some time establishing a personal connection to the topic (like I talked about for the professional community). They will likely want to know why you are interested and why you are a credible source for this information. While this group may not be experts on research, as potential members of the group(s) that you may be researching, you do want to remember that they are experts in their own community. As such, you will want to be especially mindful of approaching how you present findings with a sense of cultural humility (although hopefully you have this in mind across all audiences). It will be good to discuss what steps you took to ensure that your findings accurately reflect what participants shared with you (rigor). You will want to be most clear with this group about what they should take away, without overstating your findings.

Regardless of who your audience is, remember that you are an ambassador. You may represent a topic, a population, an organization, or the whole institution of research, or any combination of these. Make sure to present your findings honestly, ethically, and clearly. Furthermore, I’m assuming that the research you are conducting is important because you have spent a lot of time and energy to arrive at your findings. Make sure that this importance comes through in your dissemination. Tell a compelling story with your research!

Exercises

Who needs to hear the message of your qualitative research?

What will they know in advance?

- Example. If you are presenting your research about caregiver fatigue to a caregiver support group, you won’t need to spend time describing the role of caregivers because your audience will have lived experience.

What terms will they likely already be familiar with and which ones will require additional explanation?

- Example. If you are presenting your research findings to a group of academics, you wouldn’t have to explain what a sampling frame is, but if you are sharing it with a group of community members from a local housing coalition, you will need to help them understand what this is (or maybe use a phrase that is more meaningful to them).

What will your audience be looking for?

- Example. If you are speaking to a group of child welfare workers about your study examining trauma-informed communication strategies, they are probably going to want to know how these strategies might impact the work that they do.

What is most impactful or valued by your audience?

- Example. If you are sharing your findings at a meeting with a council member, it may be especially meaningful to share direct quotes from constituents.

Purpose

Being clear about the purpose of your research from the outset is immeasurably helpful. What are you hoping to accomplish with your study? We can certainly look to the overarching purpose of qualitative research, that being to develop/expand/challenge/explore understanding of some topic. But, what are you specifically attempting to accomplish with your study? Two of the main reasons we conduct research are to raise awareness about a topic and to create change around some issue. Let’s say you are conducting a study to better understand the experience of recidivism in the criminal justice system. This is an example of a study whose main purpose is to better understand and raise awareness around a particular social phenomenon (recidivism). On the other hand, you could also conduct a study that examines the use of strengths-based strategies by probation officers to reduce recidivism. This would fall into the category of research promoting a specific change (the use of strengths-based strategies among probation officers). I would wager that your research topic falls into one of these two very broad categories. If this is the case, how would you answer the corresponding questions below?

Exercises

Are you seeking to raise awareness of a particular issue with your research? If so,

- Whose awareness needs raising?

- What will “speak” most effectively to this group?

- How can you frame your research so that it has the most impact?

Are you seeking to create a specific change with your research? If so,

- What will that change look like?

- How can your research best support that change occurring?

- Who has the power to create that change and what will be most compelling in reaching them?

How you answer these questions will help to inform your dissemination plan. For instance, your dissemination plan will likely look very different if you are trying to persuade a group of legislators to pass a bill versus trying to share a new model or theory with academic colleagues. Considering your purposes will help you to convey the message of your research most effectively and efficiently. We invest a lot of ourselves in our research, so make sure to keep your sights focused on what you hope to accomplish with it!

Content and context

As a reminder, qualitative research often has a dual responsibility for conveying both content and context. You can think of content as the actual data that is shared with us or that we obtain, while context is the circumstances under which that data sharing occurs. Content conveys the message and context provides us the clues with which we can decode and make sense of that message.

While quantitative research may provide some contextual information, especially in regards to describing its sample, it rarely receives as much attention or detail as it does in qualitative studies. Because of this, you will want to plan for how you will attend to both the content and context of your study in planning for your dissemination.

Key Takeaways

- Research is an intentional act; you are trying to accomplish something with it. To be successful, you need to approach dissemination planfully.

- Planning the most effective way of sharing our qualitative findings requires looking beyond what is convenient or even conventional, and requires us to consider a number of factors, including our audience, the purpose or intent of our research and the nature of both the content and the context that we are trying to convey.

21.4 Final product taking shape

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Evaluate the various means of disseminating research and consider their applicability for your research project

- Determine appropriate building blocks for designing your qualitative research product

As we have discussed, qualitative research takes many forms. It should then come as no surprise that qualitative research products also come in many different packages. To help guide you as the final products of your research take shape, we will discuss some of the building blocks or elements that you are likely to include as tools in sharing your qualitative findings. These are the elements that will allow you to flesh out the details of your dissemination plan.

Building blocks

There are many building blocks that are at our disposal as we formulate our qualitative research product(s). Quantitative researchers have charts, graphs, tables, and narrative descriptions of numerical output. These tools allow the quantitative researcher to tell the story of their research with numbers. As qualitative researchers, we are tasked with telling the story of our research findings as well, but our tools look different. While this isn’t an exhaustive list of tools that are at our disposal as qualitative researchers, a number of commonly used elements in sharing qualitative findings are discussed here. Depending on your study design and the type of data you are working with, you may use one or some combination of the building blocks discussed below.

Themes

Themes are a very common element when presenting qualitative research findings. They may be called themes, but they may also go by other names: categories, dimensions, main ideas, etc. Themes offer the qualitative researcher a way to share ideas that emerged from your analysis that were shared by multiple participants or across multiple sources of data. They help us to distill the large amounts of qualitative data that we might be working with into more concise and manageable pieces of information that are more consumable for our audience. When integrating themes into your qualitative research product, you will want to offer your audience: the title of the theme (try to make this as specific/meaningful as possible), a brief description or definition of the theme, any accompanying dimensions or sub-themes that may be relevant, and examples (when appropriate).

Quotes

Quotes offer you the opportunity to share participants’ exact words with your audience. Of course, we can’t only rely on quotes, because we need to knit the information that is shared into one cohesive description of our findings and an endless list of quotes is unlikely to support this. Because of this, you will want to be judicious in selecting your quotes. Choose quotes that can stand on their own, best reflect the sentiment that is being captured by the theme or category of findings that you are discussing, and are likely to speak to and be understood by your audience. Quotes are a great way to help your findings come alive or to give them greater depth and significance. If you are using quotes, be sure to do so in a balanced manner—don’t only use them in some sections but not others, or use a large number to support one theme and only one or two for another. Finally, we often provide some brief demographic information in a parenthetical reference following a quote so our reader knows a little bit about the person who shared the information. This helps to provide some context for the quote.

Kohli and Pizarro (2016)[2] provide a good example of a qualitative study using quotes to exemplify their themes. In their study, they gathered data through short-answer questionnaires and in-depth interviews from racial-justice oriented teachers of Color. Their study explored the experiences and motivations of these teachers and the environments in which they worked. As you might guess, the words of the teacher-participants were especially powerful and the quotes provided in the results section were very informative and important in helping to fulfill the aim of the research study. Take a few minutes to review this article. Note how the authors provide a good amount of detail as to what each of the themes meant and how they used the quotes to demonstrate and support each theme. The quotes help bring the themes to life and anchor the results in the actual words of the participants (suggesting greater trustworthiness in the findings).

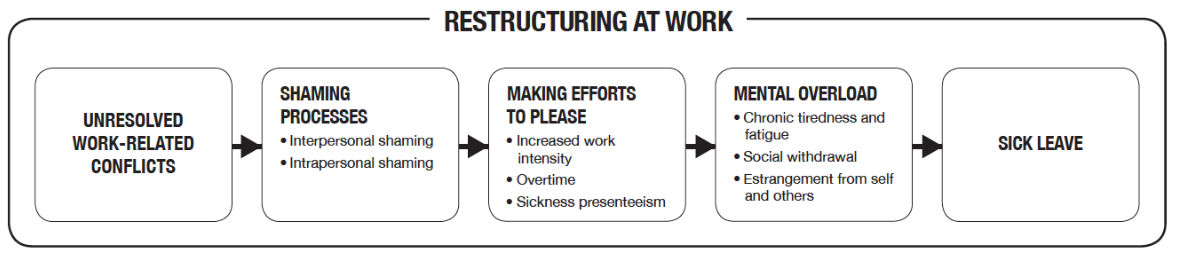

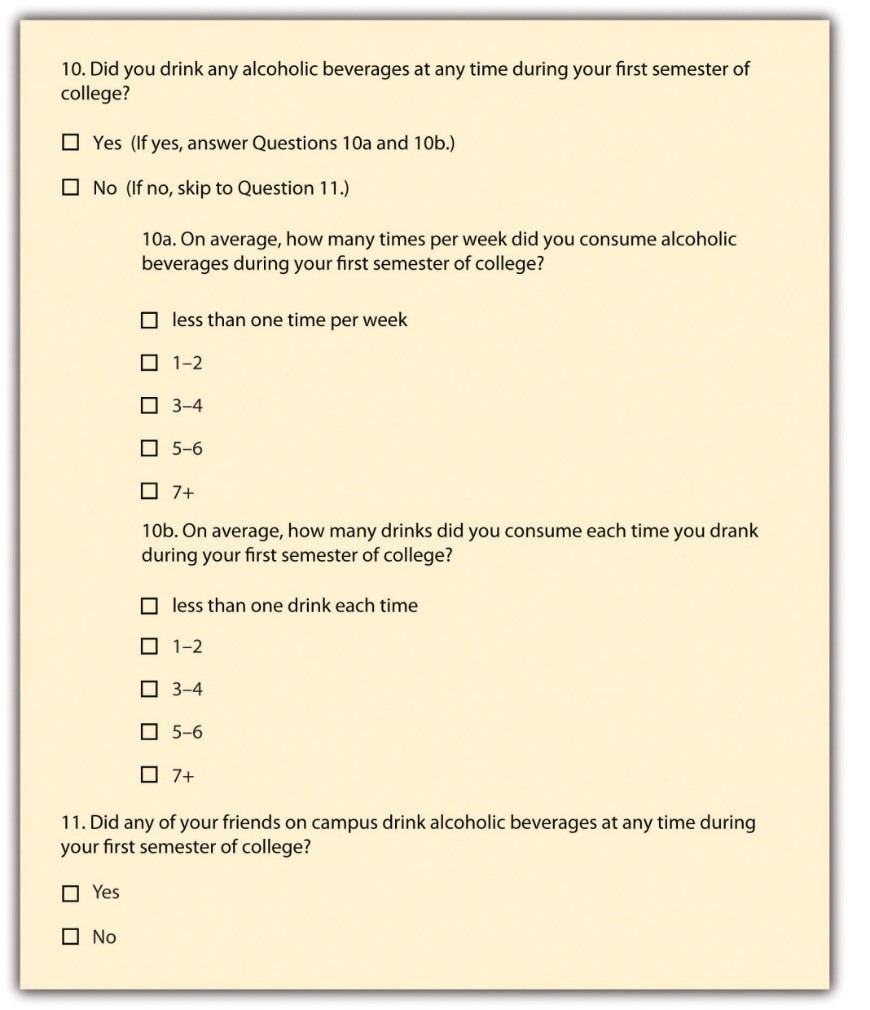

Figure 21.1 below offers a more extensive example of a theme being reported along with supporting quotes from a study conducted by Karabanow, Gurman, and Naylor (2012).[3] This study focused on the role of work activities in the lives of “Guatemalan street youth”. One of the important themes had to do with intersection of work and identity for this group. In this example, brief quotes are used within the body of the description of the theme, and also longer quotes (full sentence(s)) to demonstrate important aspects of the description.

Work-based Identity: Creativity and Self-WorthWork, be it formal or informal, is beneficial for street youth not only for its financial benefits; but it helps youth to develop and rebuild their sense of self, to break away from destructive patterns, and ultimately contributes to any goals of exiting street life. Although many of the participants were aware that society viewed them as “lazy” or “useless,” they tended to see themselves as contributing members of society earning a valid and honest living. One participant said, “Well, a lot of people say, right? ‘The kid doesn’t want to do anything. Lazy kid’ right? And I wouldn’t like for people to say that about me, I’d rather do something so that they don’t say that I’m lazy. I want to be someone important in life.” This youth makes an interesting and important connection in this statement: he intrinsically associates “being someone” with “doing something” – he accepts the work-based identity that characterizes much of contemporary capitalist society. Many of the interviews subtly enforced this idea that in the informal economy, as in the formal economy, “who one is” is largely dependent on “what one does.” This demonstrates two important ideas: that street youth working in the informal sector are surprisingly ‘mainstream’ in their underlying beliefs and ambitions, and that work – be it formal or informal – plays a crucial role in allowing street youth, who have often dealt with trauma, isolation and low self-esteem, to rebuild a sense of self-worth. Many of the youth involved in this study dream of futures that echo traditional ideals: “to have my family all together…to have a home, or rather to have a nice house…to have a good job.” Several explained that this future is unattainable without hard work; many viewed those who “do nothing” as people who “waste their time” and think that “your life isn’t important to you.” On the other hand, those who value their lives and wish to attain a future of “peace and tranquility” must “look for work, that’s what needs to be done to have that future because if God allows it, in the future maybe you can find a partner, form a family and live peacefully.” For these youth, working – be it in the formal or informal sector – is essential to a feeling of “moving forward (seguir adelante).” This movement forward begins with self-esteem. Although the focus of this study was not the troubled pasts of the participants, many alluded to the difficulties they have faced and the various traumas that forced them onto the streets. Several of the youth noted that working was a catalyst in rebuilding positive feelings about oneself: one explained, “[When I’m working,] I feel happy, powerful…Sometimes when I go out to sell, I feel happy.” Another said: For me, when I’m working I feel free because I know that I’m earning my money in an honest way, not stealing right. Because when you’re stealing, you don’t feel free, right? Now when you’re working, you’re free, they can’t arrest you or anything because you’re selling. Now if you’re stealing and everything, you don’t feel free. But when you’re selling you feel free, out of danger. This feeling of being “free” or “powerful” rests on the idea that money is “earned” and not stolen; being able to earn money is associated with being “someone,” with being a valid and contributing member of society. In addition, work helps street youth to break away from destructive patterns. One participant spoke of her experience working full time at a café: For me, working means to be busy, to not just be there….It helps us meet other people, like new people and not to be always in the same scene. Because if you’re not busy, you feel really bored and you might want to, I don’t know, go back to the same thing you were in before…you even forget your problems because you’re keeping busy, you’re talking to other people, people who don’t know you. For this participant, a formal job was beneficial in that it supplied her with a daily routine and allowed her to interact with non-street people – these factors helped to separate her from the destructive lifestyle of the street, and helped her to “move forward.” Although these benefits are indeed most obvious with formal employment, many participants spoke of the positive effects of informal work as well, although to varying degrees. In Guatemala, since the informal economy accounts for over half of the country’s GNP, there is a wide range of under-the-table informal work available. These jobs frequently bring youth out of the street context and, therefore, provide similar benefits to a formal job, as described by the above participant. As to informal work that takes place on the street, such as hawking or car watching, the benefits of work are present, although to a different degree. Even hawking, for example, gives young workers a routine and a chance to interact with non-street people. As one young man continuously emphasized throughout his interview, “work helps you to keep your mind busy, to be in another mind-set, right? To not be thinking the same thing all the time: ‘Oh, drugs, drugs, drugs…’” As explained earlier, the code of the hawking world dictates that vendors cannot sell while high – just like a formal job, hawking helps to distance youth workers from some of their destructive street habits. However, as one participant thoughtfully noted, it is difficult to break these habits when one is still highly embroiled in street culture; “it depended on who was around me because if they were in the same problems as I was, I stopped working and I started doing the same as they did. And if I was surrounded by serious people, then I got my act together.” While certain types of informal work, like cleaning or waitressing, can help youth to distance themselves from destructive patterns, others, such as car watching and selling, may not do enough to separate youth from their peers. While the routine and activity do have positive effects, they often are not sufficient. Among some of the participants, there was the sentiment that informal work could function as a transition stage towards exiting the street; it could “change your life.” One participant said “there are lots of vendors who’ve gotten off the streets, if you make an effort, you go out to sell, you can get off the street. Like myself, when I was selling, I mean working, I got off the street, I went home and I managed to stay there quite a long time.” One might credit this success to several factors: first, the money the seller may have been able to save and accumulate; second, the routine of selling may have helped the seller to break from destructive patterns, such as drug use, and also prepared the seller for the demands of formal sector employment; and, thirdly, selling may have enabled the seller to develop the necessary confidence and sense of self to attempt exiting the street. |

Pictures or videos

If our data collection involves the use of photographs, drawings, videos or other artistic expression of participants or collection of artifacts, we may very well include selections of these in our dissemination of qualitative findings. In fact, if we failed to include these, it would seem a bit inauthentic. For the same reason we include quotes as direct representations of participants’ contributions, it is a good idea to provide direct reference to other visual forms of data that support or demonstrate our findings. We might incorporate narrative descriptions of these elements or quotes from participants that help to interpret their meaning. Integrating pictures and quotes is especially common if we are conducting a study using a Photovoice approach, as we discussed in Chapter 17, where a main goal of the research technique is to bring together participant generated visuals with collaborative interpretation.

Take some time to explore the website linked here. It is the webpage for The Philidelphia Collaborative for Health Equity’s PhotoVoice Exhibit Gallery and offers a good demonstration of research that brings together pictures and text.

Graphic or figure

Qualitative researchers will often create a graphic or figure to visually reflect how the various pieces of your findings come together or relate to each other. Using a visual representation can be especially compelling for people who are visual learners. When you are using a visual representation, you will want to: label all elements clearly; include all the components or themes that are part of your findings; pay close attention to where you place and how you orient each element (as their spatial arrangement carries meaning); and finally, offer a brief but informative explanation that helps your reader to interpret your representation. A special subcategory of visual representation is process. These are especially helpful to lay out a sequential relationship within your findings or a model that has emerged out of your analysis. A process or model will show the ‘flow’ of ideas or knowledge in our findings, the logic of how one concept proceeds to the next and what each step of the model entails.

Noonan and colleagues (2004)[4] conducted a qualitative study that examined the career development of high achieving women with physical and sensory disabilities. Through the analysis of their interviews, they built a model of career development based on these women’s experiences with a figure that helps to conceptually illustrate the model. They place the ‘dyanmic self’ in the center, surrounded by a dotted (permeable) line, with a number of influences outside the line (i.e. family influences, disability impact, career attitudes and behaviors, sociopoltical context, developmental opportunities and social support) and arrows directed inward and outward between each influence and the dynamic self to demonstrate mutual influence/exchange between them. The image is included in the results section of their study and brings together “core categories” and demonstrates how they work together in the emergent theory or how they relate to each other. Because so many of our findings are dynamic, like Noonan and colleagues, showing interaction and exchange between ideas, figures can be especially helpful in conveying this as we share our results.

Composites

Going one step further than the graphic or figure discussed above, qualitative researchers may decide to combine and synthesize findings into one integrated representation. In the case of the graphic or figure, the individual elements still maintain their distinctiveness, but are brought together to reflect how they are related. In a composite however, rather than just showing that they are related (static), the audience actually gets to ‘see’ the elements interacting (dynamic). The integrated and interactive findings of a composite can take many forms. It might be a written narrative, such as a fictionalized case study that reflects of highlights the many aspects that emerged during analysis. It could be a poem, dance, painting or any other performance or medium. Ultimately, a composite offers an audience a meaningful and comprehensive expression of our findings. If you are choosing to utilize a composite, there is an underlying assumption that is conveyed: you are suggesting that the findings of your study are best understood holistically. By discussing each finding individually, they lose some of their potency or significance, so a composite is required to bring them together. As an example of a composite, consider that you are conducting research with a number of First Nations Peoples in Canada. After consulting with a number of Elders and learning about the importance of oral traditions and the significance of storytelling, you collaboratively determine that the best way to disseminate your findings will be to create and share a story as a means of presenting your research findings. The use of composites also assumes that the ‘truths’ revealed in our data can take many forms. The Transgender Youth Project hosted by the Mandala Center for Change, is an example of legislative theatre combining research, artistic expression, and political advocacy and a good example of action-oriented research.

Counts

While you haven’t heard much about numbers in our qualitative chapters, I’m going to break with tradition and speak briefly about them here. For many qualitative projects we do include some numeric information in our final product(s), mostly in the way of counts. Counts usually show up in the way of frequency of demographic characteristics of our sample or characteristics regarding our artifacts, if they aren’t people. These may be included as a table or they may be integrated into the narrative we provide, but in either case, our goal in including this information is to offer the reader information so they can better understand who or what our sample is representing. The other time we sometimes include count information is in respect to the frequency and coverage of the themes or categories that are represented in our data. Frequency information about a theme can help the reader to know how often an idea came up in our analysis, while coverage can help them to know how widely dispersed this idea was (e.g. did nearly everyone mention this, or was it a small group of participants).

Key Takeaways

- There are a wide variety of means by which you can deliver your qualitative research to the public. Choose one that takes into account the various considerations that we have discussed above and also honors the ethical commitments that we outlined early in this chapter.

- Presenting qualitative research requires some amount of creativity. Utilize the building blocks discussed in this chapter to help you consider how to most authentically and effectively convey your message to a wider audience.

Exercises

- What means of delivery will you be choosing for your dissemination plan?

- What building blocks will best convey your qualitative results to your audience?

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). NASW code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English ↵

- Kohli, R., & Pizarro, M. (2016). Fighting to educate our own: Teachers of Color, relational accountability, and the struggle for racial justice. Equity & Excellence in Education, 49(1), 72-84. ↵

- Karabanow, J., Gurman, E., & Naylor, T. (2012). Street youth labor as an Expression of survival and self-worth. Critical Social Work, 13(2). ↵

- Noonan, B. M., Gallor, S. M., Hensler-McGinnis, N. F., Fassinger, R. E., Wang, S., & Goodman, J. (2004). Challenge and success: A Qualitative study of the career development of highly achieving women with physical and sensory disabilities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 68. ↵

- Ede, L., & Starrin, B. (2014). Unresolved conflicts and shaming processes: risk factors for long-term sick leave for mental-health reasons. Nordic Journal of Social Research, 5, 39-54. ↵

Conditions that are not directly observable and represent states of being, experiences, and ideas.

The extent to which a measure “covers” the construct of interest, i.e., it's comprehensiveness to measure the construct.

Chapter Outline

- Developing your theoretical framework

- Conceptual definitions

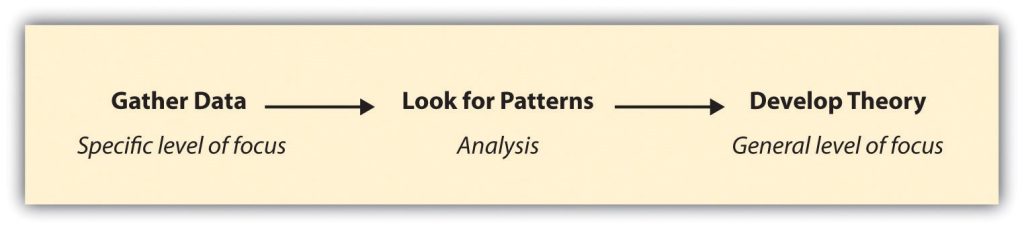

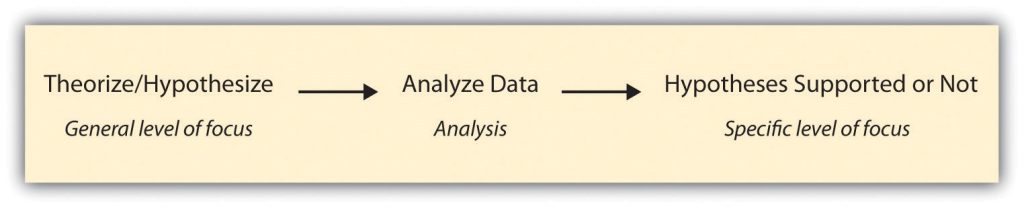

- Inductive & deductive reasoning

- Nomothetic causal explanations

Content warning: examples in this chapter include references to sexual harassment, domestic violence, gender-based violence, the child welfare system, substance use disorders, neonatal abstinence syndrome, child abuse, racism, and sexism.

11.1 Developing your theoretical framework

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Differentiate between theories that explain specific parts of the social world versus those that are more broad and sweeping in their conclusions

- Identify the theoretical perspectives that are relevant to your project and inform your thinking about it

- Define key concepts in your working question and develop a theoretical framework for how you understand your topic.

Theories provide a way of looking at the world and of understanding human interaction. Paradigms are grounded in big assumptions about the world—what is real, how do we create knowledge—whereas theories describe more specific phenomena. Well, we are still oversimplifying a bit. Some theories try to explain the whole world, while others only try to explain a small part. Some theories can be grouped together based on common ideas but retain their own individual and unique features. Our goal is to help you find a theoretical framework that helps you understand your topic more deeply and answer your working question.

Theories: Big and small

In your human behavior and the social environment (HBSE) class, you were introduced to the major theoretical perspectives that are commonly used in social work. These are what we like to call big-T 'T'heories. When you read about systems theory, you are actually reading a synthesis of decades of distinct, overlapping, and conflicting theories that can be broadly classified within systems theory. For example, within systems theory, some approaches focus more on family systems while others focus on environmental systems, though the core concepts remain similar.

Different theorists define concepts in their own way, and as a result, their theories may explore different relationships with those concepts. For example, Deci and Ryan's (1985)[1] self-determination theory discusses motivation and establishes that it is contingent on meeting one's needs for autonomy, competency, and relatedness. By contrast, ecological self-determination theory, as written by Abery & Stancliffe (1996),[2] argues that self-determination is the amount of control exercised by an individual over aspects of their lives they deem important across the micro, meso, and macro levels. If self-determination were an important concept in your study, you would need to figure out which of the many theories related to self-determination helps you address your working question.

Theories can provide a broad perspective on the key concepts and relationships in the world or more specific and applied concepts and perspectives. Table 7.2 summarizes two commonly used lists of big-T Theoretical perspectives in social work. See if you can locate some of the theories that might inform your project.

| Payne's (2014)[3] practice theories | Hutchison's (2014)[4] theoretical perspectives |

| Psychodynamic | Systems |

| Crisis and task-centered | Conflict |

| Cognitive-behavioral | Exchange and choice |

| Systems/ecological | Social constructionist |

| Macro practice/social development/social pedagogy | Psychodynamic |

| Strengths/solution/narrative | Developmental |

| Humanistic/existential/spiritual | Social behavioral |

| Critical | Humanistic |

| Feminist | |

| Anti-discriminatory/multi-cultural sensitivity |

Competing theoretical explanations

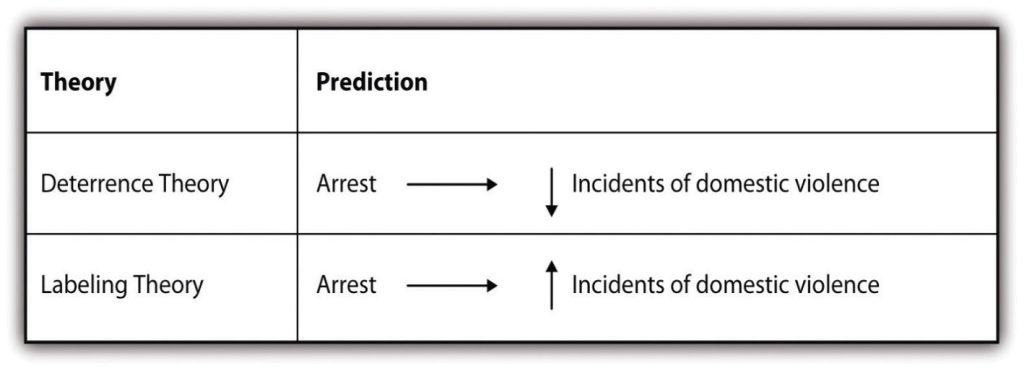

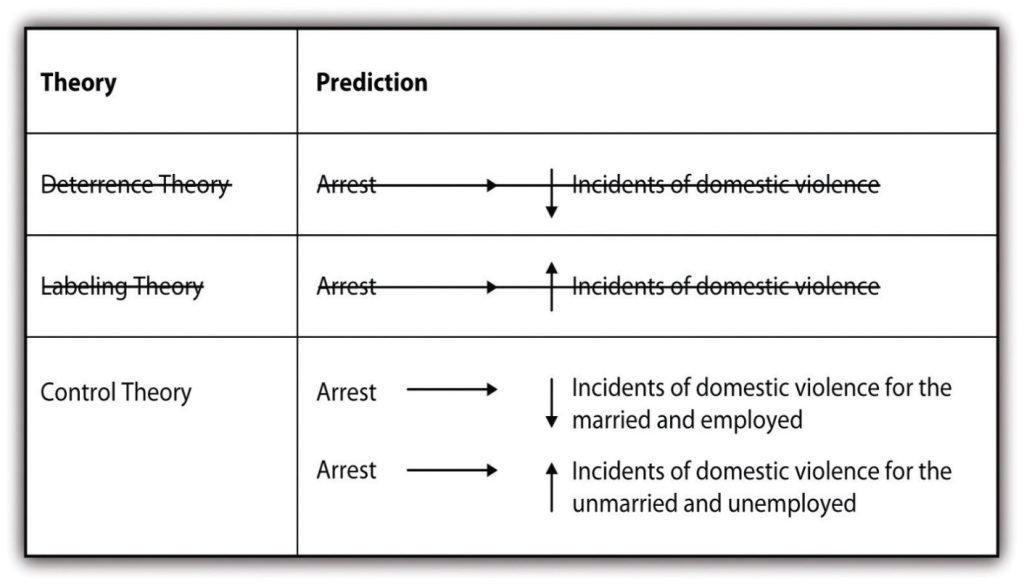

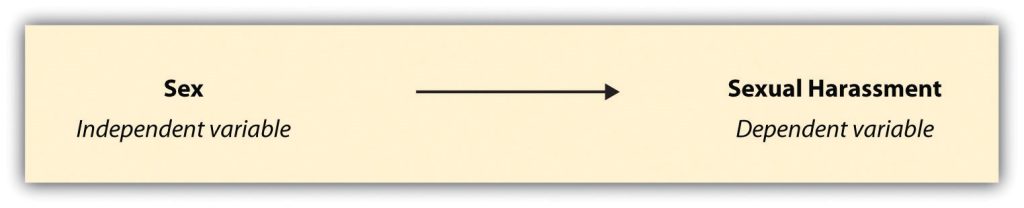

Within each area of specialization in social work, there are many other theories that aim to explain more specific types of interactions. For example, within the study of sexual harassment, different theories posit different explanations for why harassment occurs.

One theory, first developed by criminologists, is called routine activities theory. It posits that sexual harassment is most likely to occur when a workplace lacks unified groups and when potentially vulnerable targets and motivated offenders are both present (DeCoster, Estes, & Mueller, 1999).[5]

Other theories of sexual harassment, called relational theories, suggest that one's existing relationships are the key to understanding why and how workplace sexual harassment occurs and how people will respond when it does occur (Morgan, 1999).[6] Relational theories focus on the power that different social relationships provide (e.g., married people who have supportive partners at home might be more likely than those who lack support at home to report sexual harassment when it occurs).

Finally, feminist theories of sexual harassment take a different stance. These theories posit that the organization of our current gender system, wherein those who are the most masculine have the most power, best explains the occurrence of workplace sexual harassment (MacKinnon, 1979).[7] As you might imagine, which theory a researcher uses to examine the topic of sexual harassment will shape the questions asked about harassment. It will also shape the explanations the researcher provides for why harassment occurs.

For a graduate student beginning their study of a new topic, it may be intimidating to learn that there are so many theories beyond what you’ve learned in your theory classes. What’s worse is that there is no central database of theories on your topic. However, as you review the literature in your area, you will learn more about the theories scientists have created to explain how your topic works in the real world. There are other good sources for theories, in addition to journal articles. Books often contain works of theoretical and philosophical importance that are beyond the scope of an academic journal. Do a search in your university library for books on your topic, and you are likely to find theorists talking about how to make sense of your topic. You don't necessarily have to agree with the prevailing theories about your topic, but you do need to be aware of them so you can apply theoretical ideas to your project.

Applying big-T theories to your topic

The key to applying theories to your topic is learning the key concepts associated with that theory and the relationships between those concepts, or propositions. Again, your HBSE class should have prepared you with some of the most important concepts from the theoretical perspectives listed in Table 7.2. For example, the conflict perspective sees the world as divided into dominant and oppressed groups who engage in conflict over resources. If you were applying these theoretical ideas to your project, you would need to identify which groups in your project are considered dominant or oppressed groups, and which resources they were struggling over. This is a very general example. Challenge yourself to find small-t theories about your topic that will help you understand it in much greater detail and specificity. If you have chosen a topic that is relevant to your life and future practice, you will be doing valuable work shaping your ideas towards social work practice.

Integrating theory into your project can be easy, or it can take a bit more effort. Some people have a strong and explicit theoretical perspective that they carry with them at all times. For me, you'll probably see my work drawing from exchange and choice, social constructionist, and critical theory. Maybe you have theoretical perspectives you naturally employ, like Afrocentric theory or person-centered practice. If so, that's a great place to start since you might already be using that theory (even subconsciously) to inform your understanding of your topic. But if you aren't aware of whether you are using a theoretical perspective when you think about your topic, try writing a paragraph off the top of your head or talking with a friend explaining what you think about that topic. Try matching it with some of the ideas from the broad theoretical perspectives from Table 7.2. This can ground you as you search for more specific theories. Some studies are designed to test whether theories apply the real world while others are designed to create new theories or variations on existing theories. Consider which feels more appropriate for your project and what you want to know.

Another way to easily identify the theories associated with your topic is to look at the concepts in your working question. Are these concepts commonly found in any of the theoretical perspectives in Table 7.2? Take a look at the Payne and Hutchison texts and see if any of those look like the concepts and relationships in your working question or if any of them match with how you think about your topic. Even if they don't possess the exact same wording, similar theories can help serve as a starting point to finding other theories that can inform your project. Remember, HBSE textbooks will give you not only the broad statements of theories but also sources from specific theorists and sub-theories that might be more applicable to your topic. Skim the references and suggestions for further reading once you find something that applies well.

Exercises

Choose a theoretical perspective from Hutchison, Payne, or another theory textbook that is relevant to your project. Using their textbooks or other reputable sources, identify :

- At least five important concepts from the theory

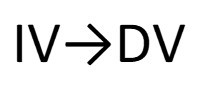

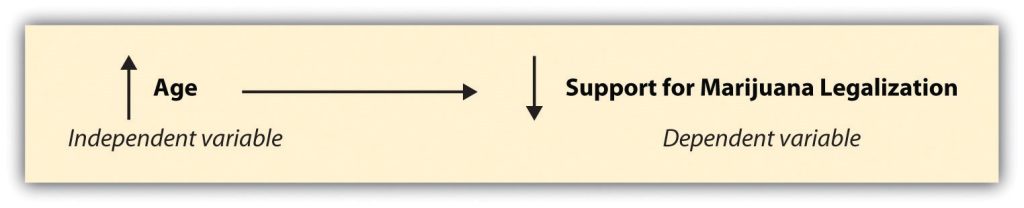

- What relationships the theory establishes between these important concepts (e.g., as x increases, the y decreases)

- How you can use this theory to better understand the concepts and variables in your project?

Developing your own theoretical framework

Hutchison's and Payne's frameworks are helpful for surveying the whole body of literature relevant to social work, which is why they are so widely used. They are one framework, or way of thinking, about all of the theories social workers will encounter that are relevant to practice. Social work researchers should delve further and develop a theoretical or conceptual framework of their own based on their reading of the literature. In Chapter 8, we will develop your theoretical framework further, identifying the cause-and-effect relationships that answer your working question. Developing a theoretical framework is also instructive for revising and clarifying your working question and identifying concepts that serve as keywords for additional literature searching. The greater clarity you have with your theoretical perspective, the easier each subsequent step in the research process will be.

Getting acquainted with the important theoretical concepts in a new area can be challenging. While social work education provides a broad overview of social theory, you will find much greater fulfillment out of reading about the theories related to your topic area. We discussed some strategies for finding theoretical information in Chapter 3 as part of literature searching. To extend that conversation a bit, some strategies for searching for theories in the literature include:

- Using keywords like "theory," "conceptual," or "framework" in queries to better target the search at sources that talk about theory.

- Consider searching for these keywords in the title or abstract, specifically

- Looking at the references and cited by links within theoretical articles and textbooks

- Looking at books, edited volumes, and textbooks that discuss theory

- Talking with a scholar on your topic, or asking a professor if they can help connect you to someone

- Looking at how researchers use theory in their research projects

- Nice authors are clear about how they use theory to inform their research project, usually in the introduction and discussion section.

- Starting with a Big-T Theory and looking for sub-theories or specific theorists that directly address your topic area

- For example, from the broad umbrella of systems theory, you might pick out family systems theory if you want to understand the effectiveness of a family counseling program.

It's important to remember that knowledge arises within disciplines, and that disciplines have different theoretical frameworks for explaining the same topic. While it is certainly important for the social work perspective to be a part of your analysis, social workers benefit from searching across disciplines to come to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. Reaching across disciplines can provide uncommon insights during conceptualization, and once the study is completed, a multidisciplinary researcher will be able to share results in a way that speaks to a variety of audiences. A study by An and colleagues (2015)[8] uses game theory from the discipline of economics to understand problems in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. In order to receive TANF benefits, mothers must cooperate with paternity and child support requirements unless they have "good cause," as in cases of domestic violence, in which providing that information would put the mother at greater risk of violence. Game theory can help us understand how TANF recipients and caseworkers respond to the incentives in their environment, and highlight why the design of the "good cause" waiver program may not achieve its intended outcome of increasing access to benefits for survivors of family abuse.

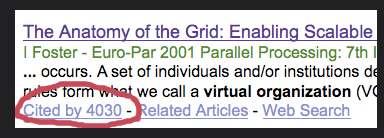

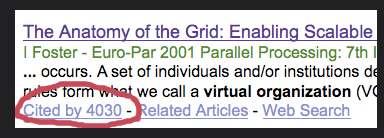

Of course, there are natural limits on the depth with which student researchers can and should engage in a search for theory about their topic. At minimum, you should be able to draw connections across studies and be able to assess the relative importance of each theory within the literature. Just because you found one article applying your theory (like game theory, in our example above) does not mean it is important or often used in the domestic violence literature. Indeed, it would be much more common in the family violence literature to find psychological theories of trauma, feminist theories of power and control, and similar theoretical perspectives used to inform research projects rather than game theory, which is equally applicable to survivors of family violence as workers and bosses at a corporation. Consider using the Cited By feature to identify articles, books, and other sources of theoretical information that are seminal or well-cited in the literature. Similarly, by using the name of a theory in the keywords of a search query (along with keywords related to your topic), you can get a sense of how often the theory is used in your topic area. You should have a sense of what theories are commonly used to analyze your topic, even if you end up choosing a different one to inform your project.

Theories that are not cited or used as often are still immensely valuable. As we saw before with TANF and "good cause" waivers, using theories from other disciplines can produce uncommon insights and help you make a new contribution to the social work literature. Given the privileged position that the social work curriculum places on theories developed by white men, students may want to explore Afrocentricity as a social work practice theory (Pellebon, 2007)[9] or abolitionist social work (Jacobs et al., 2021)[10] when deciding on a theoretical framework for their research project that addresses concepts of racial justice. Start with your working question, and explain how each theory helps you answer your question. Some explanations are going to feel right, and some concepts will feel more salient to you than others. Keep in mind that this is an iterative process. Your theoretical framework will likely change as you continue to conceptualize your research project, revise your research question, and design your study.

By trying on many different theoretical explanations for your topic area, you can better clarify your own theoretical framework. Some of you may be fortunate enough to find theories that match perfectly with how you think about your topic, are used often in the literature, and are therefore relatively straightforward to apply. However, many of you may find that a combination of theoretical perspectives is most helpful for you to investigate your project. For example, maybe the group counseling program for which you are evaluating client outcomes draws from both motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. In order to understand the change happening in the client population, you would need to know each theory separately as well as how they work in tandem with one another. Because theoretical explanations and even the definitions of concepts are debated by scientists, it may be helpful to find a specific social scientist or group of scientists whose perspective on the topic you find matches with your understanding of the topic. Of course, it is also perfectly acceptable to develop your own theoretical framework, though you should be able to articulate how your framework fills a gap within the literature.

If you are adapting theoretical perspectives in your study, it is important to clarify the original authors' definitions of each concept. Jabareen (2009)[11] offers that conceptual frameworks are not merely collections of concepts but, rather, constructs in which each concept plays an integral role.[12] A conceptual framework is a network of linked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. Each concept in a conceptual framework plays an ontological or epistemological role in the framework, and it is important to assess whether the concepts and relationships in your framework make sense together. As your framework takes shape, you will find yourself integrating and grouping together concepts, thinking about the most important or least important concepts, and how each concept is causally related to others.

Much like paradigm, theory plays a supporting role for the conceptualization of your research project. Recall the ice float from Figure 7.1. Theoretical explanations support the design and methods you use to answer your research question. In student projects that lack a theoretical framework, I often see the biases and errors in reasoning that we discussed in Chapter 1 that get in the way of good social science. That's because theories mark which concepts are important, provide a framework for understanding them, and measure their interrelationships. If you are missing this foundation, you will operate on informal observation, messages from authority, and other forms of unsystematic and unscientific thinking we reviewed in Chapter 1.

Theory-informed inquiry is incredibly helpful for identifying key concepts and how to measure them in your research project, but there is a risk in aligning research too closely with theory. The theory-ladenness of facts and observations produced by social science research means that we may be making our ideas real through research. This is a potential source of confirmation bias in social science. Moreover, as Tan (2016)[13] demonstrates, social science often proceeds by adopting as true the perspective of Western and Global North countries, and cross-cultural research is often when ethnocentric and biased ideas are most visible. In her example, a researcher from the West studying teacher-centric classrooms in China that rely partially on rote memorization may view them as less advanced than student-centered classrooms developed in a Western country simply because of Western philosophical assumptions about the importance of individualism and self-determination. Developing a clear theoretical framework is a way to guard against biased research, and it will establish a firm foundation on which you will develop the design and methods for your study.

Key Takeaways

- Just as empirical evidence is important for conceptualizing a research project, so too are the key concepts and relationships identified by social work theory.

- Using theory your theory textbook will provide you with a sense of the broad theoretical perspectives in social work that might be relevant to your project.

- Try to find small-t theories that are more specific to your topic area and relevant to your working question.

Exercises

- In Chapter 2, you developed a concept map for your proposal. Take a moment to revisit your concept map now as your theoretical framework is taking shape. Make any updates to the key concepts and relationships in your concept map.

. If you need a refresher, we have embedded a short how-to video from the University of Guelph Library (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0) that we also used in Chapter 2.

11.2 Conceptual definitions

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Define measurement and conceptualization

- Apply Kaplan’s three categories to determine the complexity of measuring a given variable

- Identify the role previous research and theory play in defining concepts

- Distinguish between unidimensional and multidimensional concepts

- Critically apply reification to how you conceptualize the key variables in your research project

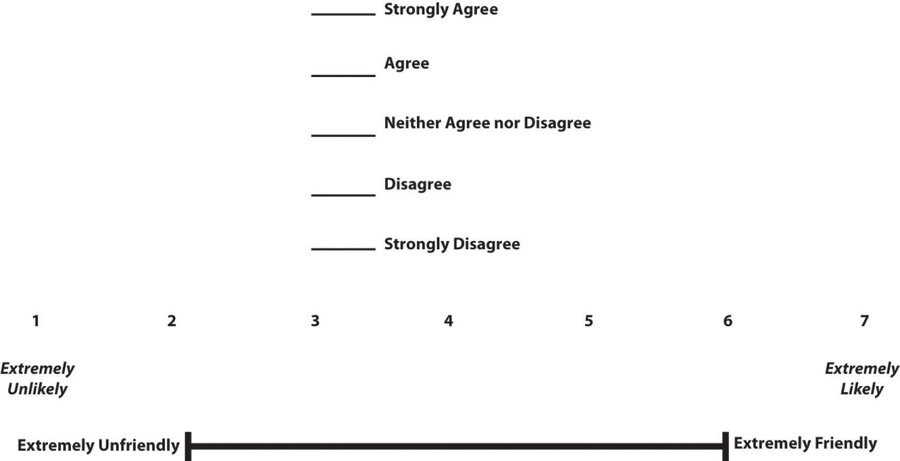

In social science, when we use the term measurement, we mean the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms in as clear and precise a way as possible. Of course, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using a measuring cup or spoon, but there are some basic tenets on which most social scientists agree when it comes to measurement. We’ll explore those, as well as some of the ways that measurement might vary depending on your unique approach to the study of your topic.

An important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. What it does require is a systematic procedure for assigning scores, meanings, and descriptions to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest. You can measure phenomena in many different ways, but you must be sure that how you choose to measure gives you information and data that lets you answer your research question. If you're looking for information about a person's income, but your main points of measurement have to do with the money they have in the bank, you're not really going to find the information you're looking for!

The question of what social scientists measure can be answered by asking yourself what social scientists study. Think about the topics you’ve learned about in other social work classes you’ve taken or the topics you’ve considered investigating yourself. Let’s consider Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner’s study (2011)[14] of first graders’ mental health. In order to conduct that study, Milkie and Warner needed to have some idea about how they were going to measure mental health. What does mental health mean, exactly? And how do we know when we’re observing someone whose mental health is good and when we see someone whose mental health is compromised? Understanding how measurement works in research methods helps us answer these sorts of questions.

As you might have guessed, social scientists will measure just about anything that they have an interest in investigating. For example, those who are interested in learning something about the correlation between social class and levels of happiness must develop some way to measure both social class and happiness. Those who wish to understand how well immigrants cope in their new locations must measure immigrant status and coping. Those who wish to understand how a person’s gender shapes their workplace experiences must measure gender and workplace experiences (and get more specific about which experiences are under examination). You get the idea. Social scientists can and do measure just about anything you can imagine observing or wanting to study. Of course, some things are easier to observe or measure than others.

Observing your variables

In 1964, philosopher Abraham Kaplan (1964)[15] wrote The Conduct of Inquiry, which has since become a classic work in research methodology (Babbie, 2010).[16] In his text, Kaplan describes different categories of things that behavioral scientists observe. One of those categories, which Kaplan called “observational terms,” is probably the simplest to measure in social science. Observational terms are the sorts of things that we can see with the naked eye simply by looking at them. Kaplan roughly defines them as conditions that are easy to identify and verify through direct observation. If, for example, we wanted to know how the conditions of playgrounds differ across different neighborhoods, we could directly observe the variety, amount, and condition of equipment at various playgrounds.

Indirect observables, on the other hand, are less straightforward to assess. In Kaplan's framework, they are conditions that are subtle and complex that we must use existing knowledge and intuition to define. If we conducted a study for which we wished to know a person’s income, we’d probably have to ask them their income, perhaps in an interview or a survey. Thus, we have observed income, even if it has only been observed indirectly. Birthplace might be another indirect observable. We can ask study participants where they were born, but chances are good we won’t have directly observed any of those people being born in the locations they report.

Sometimes the measures that we are interested in are more complex and more abstract than observational terms or indirect observables. Think about some of the concepts you’ve learned about in other social work classes—for example, ethnocentrism. What is ethnocentrism? Well, from completing an introduction to social work class you might know that it has something to do with the way a person judges another’s culture. But how would you measure it? Here’s another construct: bureaucracy. We know this term has something to do with organizations and how they operate but measuring such a construct is trickier than measuring something like a person’s income. The theoretical concepts of ethnocentrism and bureaucracy represent ideas whose meanings we have come to agree on. Though we may not be able to observe these abstractions directly, we can observe their components.

Kaplan referred to these more abstract things that behavioral scientists measure as constructs. Constructs are “not observational either directly or indirectly” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 55),[17] but they can be defined based on observables. For example, the construct of bureaucracy could be measured by counting the number of supervisors that need to approve routine spending by public administrators. The greater the number of administrators that must sign off on routine matters, the greater the degree of bureaucracy. Similarly, we might be able to ask a person the degree to which they trust people from different cultures around the world and then assess the ethnocentrism inherent in their answers. We can measure constructs like bureaucracy and ethnocentrism by defining them in terms of what we can observe.[18]

The idea of coming up with your own measurement tool might sound pretty intimidating at this point. The good news is that if you find something in the literature that works for you, you can use it (with proper attribution, of course). If there are only pieces of it that you like, you can reuse those pieces (with proper attribution and describing/justifying any changes). You don't always have to start from scratch!

Exercises

Look at the variables in your research question.

- Classify them as direct observables, indirect observables, or constructs.

- Do you think measuring them will be easy or hard?

- What are your first thoughts about how to measure each variable? No wrong answers here, just write down a thought about each variable.

Measurement starts with conceptualization

In order to measure the concepts in your research question, we first have to understand what we think about them. As an aside, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it is important to be sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity. While there are many possible ways to define the term and some may be more common or have more support than others, there is no universal definition of masculinity. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.\