4 Reading scientific literature reviews

Chapter Outline

- Evaluating scholarly sources

- Accessing the full text of journal articles

- Critical information literacy

- Synthesizing information across sources

Content warning: examples in this chapter contain references to school discipline, mental health, gender-based discrimination, police shootings, ableism, autism and anti-vaccination conspiracy theories, children’s mental health, child abuse, poverty, substance use disorders and parenting/pregnancy, tobacco use, neocolonialism and Western hegemony, and COVID-19.

4.1 Evaluating scholarly sources

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Use skimming to identify which articles are most relevant to your topic

- Assess the bias and rigor of resources

- Match your information need to the type of article most relevant to that need

In the previous chapter, we discussed how to formulate search queries to get the most relevant results from scholarly databases. At this point, you should not be staring at a Google Scholar window with 1,000,000 search results. If you haven’t played around in multiple databases and refined your queries, pause here and spend some time working on your search queries. Hopefully, you can find at least a few different queries that provide relevant resources to help you answer your working question or introduce new ideas that might revise or update your working question. Remember that your working question should be revised and updated as you learn more about your topic by searching in the literature.

For me, searching the literature is the fun part of a literature review. I have grand ideas about reading this article and that article and every article! If a creeping sense of dread is kicking in as you ask, “How will I ever find the time to read 60 journal articles?!” You do not have to read every article or source that discusses your topic. At some point, reading another article won’t add anything new to your literature review. Additionally, some topics have been studied for so long that reading everything would take ten lifetimes. This chapter is all about how to pick the most relevant articles, write notes about them, and incorporate relevant information into a topical outline.

In the same way you do not need to read every scholarly article about your topic, you do not have to read every word of every article you cite. Instead, this chapter will teach you techniques on how to read the most relevant sections of a journal article based on the information you need. The final section of this chapter reviews techniques for data extraction. Focusing on the specific parts of the article that are most relevant to your inquiry will save you unnecessary reading.

How many sources is enough and how many sections of a journal article do you need to read? You answer should be guided, at a minimum, by your professor’s expectations. For students in my class, we prioritize review articles first and then find empirical articles that are very similar to the question the student wants to answer. Students will certainly read at least three articles front-to-back, but most articles, they use different time management strategies. At the outset, consider the scope of your project. If you plan to submit your research project for publication in journals, as an honors or graduate thesis, or a professional conference, you will need to engage in greater depth with the literature than a paper in research methods class.

Skim abstracts

All databases will give you access to an article’s abstract. The abstract is a summary of the main points of an article. It will provide the purpose of the article and summarize the author’s conclusions. Once you have a few good search queries, start skimming through abstracts and find the articles that are most relevant to your working question. Soon enough, you will find articles that are so relevant that you may decide to read the full text.

How can you tell if an articles is relevant? Raul Pacheco-Vega recommends using the AIC approach: read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion (and the discussion section, in empirical articles). For non-empirical articles, it’s a little less clear but the first few pages and last few pages of an article usually contain the author’s reading of the relevant literature and their principal conclusions. You may also want to skim the first and last sentence of each paragraph to get its topic and concluding sentence. Only read paragraphs in which you are likely to find information relevant to your working question. Skimming like this gives you the general point of the article, though you should read in detail the most valuable resource of all—another author’s literature review.

It’s impossible to read all of the literature about your topic. In my classroom, students will read about 10 articles in detail. For a few dozen more (there is no magic number), you will read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, skim the rest of the article, but ultimately never read everything. Make the most out of the articles you do read by extracting as many facts as possible from each. You are starting your research project without a lot of knowledge of the topic you want to study, and by using the literature reviews provided in academic journal articles, you can gain a lot of knowledge about a topic in a short period of time. This way, by reading only a small number of articles, you are also reading their citations and synthesis of dozens of other articles as well.

Relevance

Keeping your working question in mind, you should look at your potential sources and evaluate whether they are relevant to your inquiry. To assess the relevance of a source, ask yourself:

- Does the source will help you answer or think more deeply about your working question and target population?

- Does the information help you answer this question, challenge your assumptions, or connect your question with another topic of concern?

- Does the information present an opposing point of view, so you can show that you have addressed all sides of the argument in your paper?

- Does the article focus on your specific subtopic or does it have a more general and broad scope?

If an article isn’t helpful to you, it’s okay not to read it. No matter how good your searching skills, some articles won’t be relevant. You don’t need to read and include everything you find!

You may also want to check the relevance of the source with your professor or course syllabus. In my class, I have specific questions I will ask students to address in their literature reviews. You may want to find sources that help you answer the questions in your professor’s prompt for a literature review. For example, my prompt asks “how many people experience this problem or issue?” My students then seek out a source that helps them understand the prevalence or incidence of an issue.

Quality

Assuming the article is relevant, you should ask yourself about the quality of the source you’ve found. To refresh your memory from Chapter 2, consider these questions when evaluating the trustworthiness of a source:

- Does this source help me address what my professor expects in a literature review?

- Does this source help me answer, revise, or focus my working question?

- Is this the best source I can find? Is this a primary or secondary source?

- What is the original context of this information?

- Is there controversy surrounding this source?

- Are the publisher and author reputable and unbiased?

Reputation

Journals can have weird names! It is not always clear which journals are predatory or reputable from a quick skim. Use the SIFT skills you learned in Chapter 2. Search for the journal in Google or Bing, and see what Wikipedia and other websites say about it. Your SIFT skills can uncover whether a journal is a predatory pay-to-publish journal or is sponsored ideologically-driven organization.

The journal impact factor is a quantitative measurement that is a useful metric for how often journals are cited in the scholarly literature. The higher the impact factor, the more people use the resource. Much like judging the impact of an article by citation count, impact factor is an imperfect measure because journals with a more specialized focus or audience will have a lower impact factor because its materials are intended to be of use to a smaller audience of readers and authors.

Primary sources preferred

When assessing social scientific findings, think about the information provided to you. Social scientists should be transparent with how they collected their data, ran their analyses, and formed their conclusions. These methodological details can help you evaluate the researcher’s claims. If, on the other hand, you come across some discussion of social scientific research in a popular magazine or newspaper, chances are that you will not find the same level of detailed information that you would find in a scholarly journal article. With secondary sources like news articles, it is hard to know enough about the study to be an informed consumer of information. Always read the primary source when possible.

There is some information that even the most responsible consumer of research cannot know. Because researchers are ethically bound to keep the identity of people in our study confidential, for example, we will never know exactly who participated in a given study or sometimes even in what location it was conducted. Awareness that you may never know everything about a study should provide some humility in terms of what we can “take away” from a given report of findings. Use the SIFT technique we learned in Chapter 2 to assess the quality of a source.

Funding

Additionally, take into account whatever information is provided about a study’s funding source. Most funders want, and in fact require, that recipients acknowledge them in publications. Keep in mind that some sources may not disclose who funds them. If this information is not provided in the source from which you learned about a study, it might behoove you to do a quick search on the internet to see if you can learn more about the funding. Findings that seem to support a particular political agenda, for example, might have more or less influence on your thinking about your topic once you know if the funding posed a potential conflict of interest.

Unfortunately, researchers also sometimes engage in unethical behavior and do not disclose things that they should. For example, a recent study on COVID-19 (Bendavid et al., 2020)[1] did not disclose that it was funded by the chief executive of JetBlue, an airline company losing money from COVID-19 travel restrictions. It is alleged that this study was paid for by airline executives in order to provide scientific support for increasing the use of air travel and lifting travel restrictions. These conflicts of interest demonstrate that science is not distinct from other areas of social life that can be abused by those with more resources in order to benefit themselves.

When is a source too old?

If a source is more than five or ten years old, it will not provide what we currently know about the topic–just what we used to know. Students in my classroom can use citations from any time period, as long as they are used appropriately. Older sources are helpful for historical information, such as how our understanding of a topic has changed over time or how the prevalence of an issue has increase or decreased. Because historical analysis is rarely the focus of student literature reviews, try to limit your sources to those that are from the past decade. Doing so will also narrow down your list of results considerably in a database.

Older sources may also be important to read if they are seminal articles. As we learned in section 3.1, seminal articles are cited often in the literature. They are clearly important to a lot of scholars in the field. You can get a quick sense of how important an article is to the broader literature on a topic by looking at how many other sources cited it. If you search for the article on Google Scholar (see Figure 3.1 for an example of a search result from Google Scholar), you can see how many other sources cited this information. Generally, the higher the number of citations, the more important the article. Of course, articles that were recently published will likely have fewer citations than older articles, and the citation count is only one indicator of an article’s importance.

Consult your professor to see if they have additional guidelines on which articles are “too old” to include in a literature review.

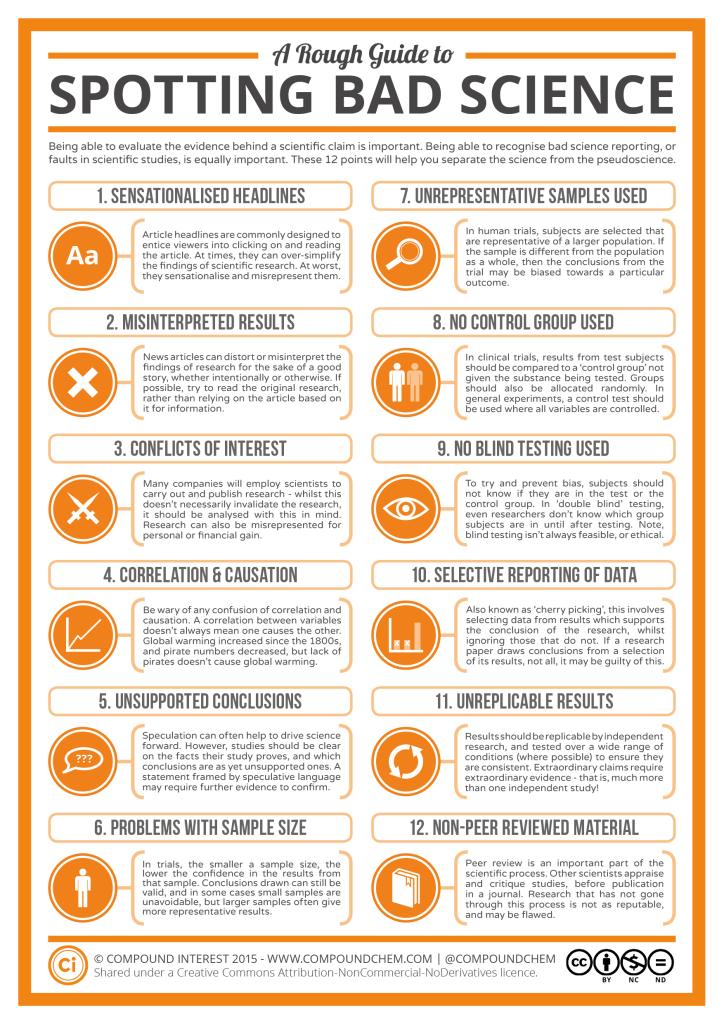

Spotting bad science

COVID-19 is a particularly instructive case in spotting bad science. In a rapidly evolving information context, social workers and others were forced to make decisions quickly using imperfect information. The Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, two of the highest-impact journals in medicine, had to retract two studies due to irregularities missed by pre-publication peer review despite the fact that the results had already been used to inform policy changes (Joseph, 2020).[2] At the same time, President Trump’s lies and misinformation about COVID-19 were a grave reminder of how information can be corrupted by those with power in the social and political arena (Paz, 2020).[3]

Figure 4.2 presents a rough guide to spotting bad science that is particularly useful when science has not had enough time for peer review and scholarly debate to thoroughly and systematically investigate a topic, as in the COVID-19 crisis. It is also a useful quick-reference guide for social work practitioners who encounter new information about their topics from the news media, social media, or other informal sources of information like friends, family, and colleagues.

What evidence is in each type of article?

Literature searching is about finding evidence to inform your ideas, supporting or refuting what you think about a topic. Each type of article we reviewed in Chapter 3 provides different kinds of evidence. A good place to start your literature search is with review articles—meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, and systematic reviews. These types of articles give you a birds-eye view of the literature in a topic area, and with meta-analyses and meta-syntheses, conduct empirical analyses on enormous datasets comprised of the raw data from multiple studies. As a result, their conclusions represent what is broadly true about the topic area. They also have comprehensive reference lists that you can browse for sources relevant to your topic.

In my experience, students are often tempted to read short articles because they can complete assignments more quickly. This is a trap for students starting a literature review. Short articles take less time to read, sure. But this isn’t about reading a certain number of articles, but finding the information you need to write your literature review as efficiently as possible. You’ll save time by reading more relevant articles with lengthier and more comprehensive literature reviews—in particular, review articles.

Review articles are the best place to start for any literature search, but you should also look for specific types of articles based on your working question. If your working question asks about an intervention, like a therapeutic technique or program, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide the strongest evidence if a meta-analysis or systematic review of relevant RCTs is unavailable. Quasi-experimental designs are considered inferior because researchers have less control over the research process, like random assignment to treatment and control groups. You will want to avoid relying heavily on articles that use non-experimental designs and include words like “pilot study,” “convenience sample,” or “exploratory study” in their methods section. These are preliminary studies that are done prior to a more rigorous experiment like an RCT, and their conclusions are tentative and collected for the purpose of informing future inquiry, not establishing what is true for broader populations. We will discuss experimental design in Chapter 13, but for now, it’s important to know that the purpose is often to establish the efficacy of an intervention and the truth value of the evidence contained in them varies based on the design of the experiment, with RCTs being the gold standard.

Experiments are one of two quantitative designs explored in this book. The other design is survey research. Looking at survey research is a good idea in any project, as it provides evidence about patterns in populations without experimenters providing a therapy or intervention. For example, surveys can tell you about the risk and protective factors for a social problem by asking valid and reliable questions to people who are likely to experience that problem over time. Longitudinal surveys are often the most helpful in understanding causality because you have a record of how things have changed over time. Cross-sectional surveys are more limited in establishing causal relationships, as they only query people at one point in time. We discuss the differences between these types of surveys in Chapter 12. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys are very commonly cited types of sources in social work literature reviews because their results are often applicable across broad populations. However, they are limited in the degree to which they can establish causality, as they lack the controlled environment of an experiment. As with experiments, students should be very cautious about using survey results that are “exploratory” or a “pilot study,” as the purpose of those studies is to inform future research rather than understand what is true about broader populations.

We will more completely discuss the impact of study design on generalizability in the next chapter. The hierarchy of evidence summarizes this relationship (McNeese & Thyer, 2004).[4] The higher a type of article on the hierarchy, the better they can reliably and directly inform evidence-based practice in social work.

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Randomized controlled trials

- Quasi-experimental studies

- Case-control and cohort studies

- Pre-experimental (or non-experimental) group studies

- Surveys

- Qualitative studies

The hierarchy of evidence is a useful heuristic, and it is based on sound reasoning. A systematic review or meta-analysis will provide you with a better picture of what is generally true for most people about a given topic than a qualitative study. However, generalizable objective truth is not the only thing researchers want to know. For example, if you wanted to research the impact of gentrification on a community, systematic reviews would not provide you the depth you need to understand the stories of people impacted, displaced, and discriminated against in housing policy. Uncovering subjective truths is not what systematic reviews are designed to do.

To find evidence like that, the most relevant evidence is in qualitative studies, at the bottom of the hierarchy. Qualitative studies are not designed to provide information about a broader population. As a result, you should treat their results as related to the specific time and place in which they occurred. If a study’s context is similar to the one you plan to research, then you might expect similar results to emerge in your research project. Qualitative studies provide the lived experience and personal reflections of people knowledgeable about your topic. These subjective truths provide evidence that is just as important as other studies in the hierarchy of evidence.

Because information needs vary, it is better to think of the hierarchy of evidence within the broader context of your working question and the knowledge you need to investigate it. Match the question you have with the study design most appropriate for your inquiry. Table 4.1 contains a suggested starting point for evaluating what types of literature will provide the most relevant evidence for your project.

| What you want know about: | The most relevant evidence will be found in this type of article |

| General knowledge about a topic | Systematic review, meta-analysis literature review, textbook, encyclopedia |

| Intervention (therapy, policy, program) | Randomized controlled trial (RCT), meta-analysis, systematic review, cohort study, case-control study, case series, clinical practice guidelines |

| Lived experience & sociocultural context | Qualitative study, participatory and action research, humanities and cultural studies |

| Theory and practice models | Theoretical and non-empirical article, textbook, manual for an evidence-based treatment, book or edited volume |

| Prevalence of a diagnosis or social problem | Survey research, government and nonprofit reports |

| How practitioners think about a topic | Practice note, survey or qualitative study of practitioners, reports from professional organizations |

Key Takeaways

- Once you have a reasonable number of search results, you can start skimming abstracts. If an article is relevant to your project, download the full text PDF to a folder on your computer.

- Download strategically, based on what your professor expects in your literature review and what information you need to understand, revise, and answer your working question.

- Write notes to yourself, so you can track how your project has developed over time.

Exercises

- Look at your professor’s prompt for a literature review and sketch out how you might answer those questions using your present level of knowledge. Search for sources that support or challenge what you think is true about your topic.

- Download and install Zotero to track your citations and store digital notes. Create a new folder for this project and add any articles you have already downloaded.

- Skim the abstracts of the articles you’ve downloaded. At the early stages of a literature review, you should prioritize finding highly relevant review articles.

4.2 Accessing the full text of journal articles

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Request an article from your library via inter-library loan

- Distinguish between the colors of open access

- Define information privilege and assess how practitioners and students vary in access to information

- Explore techniques for accessing scholarly articles after graduation

The previous section could be completed by skimming the abstract of any potentially interesting journal article, and if necessary, the introduction and discussion/conclusion sections. Abstracts are a great place to start, but you need to access the full text of articles for your student research project. I’ve often seen student papers where they do a simple Google Scholar search and only read articles for which there is free access, with the PDF link in the search results. You should be able to access the full text for most of the journal articles you need using your library’s website. Do not limit your literature search to the free articles or sketchy PDFs you find on the internet! These mistakes are opportunities for growth in information literacy skills, as students develop access patterns that will last into a lifetime of research-informed practice

Paywalls

While abstracts are available to everyone with an internet connection free of charge, that is not the case with the full text. A paywall is when a publisher charges you to access a publication.

Paywalls are barriers to evidence-based practice for practitioners, clients, and communities in the United States as well as university-affiliated and independent researchers across the globe. From 1986-2015, the price of journal subscriptions increased 521%, (Association of Research Libraries, n.d. as cited in University of Iowa, n.d.)[5] approaching 75% of the entire budget for college libraries (Shu et al., 2018) [6]. Librarians at the University of Virginia, the flagship state university, created a hilarious short quiz on the impact of scholarly journal costs.

As the quiz demonstrates, even students at well-funded research institutions will regularly encounter paywalls. The skills you develop now in circumventing paywalls will serve you well as a social work practitioner, when you lose access to university library collections.

University library

While you are studying at your university, your login is the key to unlock the paywall and grant you access to all scientific information. Part of the tuition and fees your university charges you goes toward paying major publishers of academic journals for the privilege of accessing their articles. Use your library’s website to gain access to the full text of each journal article you need for your literature search.

A few techniques from previous chapters are worth repeating to get easy, one-click access to the databases paid for via tuition and fees.. Bookmark the webpage for your library’s advanced search so you can quickly apply the techniques from Chapter 3 when searching (for example, by searching in the Abstract for your keywords). Additionally, link your university library login with your Google account so that Google Scholar provides full-text links for its search results. For the journals in your library’s subscriptions, Google Scholar will provide you with the same one-click access to the full text of the article that your library search provides.

Inter-library loan

Because journal publishers charge a lot of money for access to journals, your school likely does not pay for all the journals in the world. If your university does not already pay for access to the article you need, they will still get it for you. You will need to use the inter-library loan feature on your library’s website. It is often listed under Services. If you use your library’s search to find scholarly articles, it will offer interlibrary loan as an access option. Click the inter-library loan link, and most of the information for your article should be autocompleted in the form.

If not autocompleted, enter your article’s information directly into the form in inter-library loan system. In my experience as a professor in the Mid-Atlantic, universities use the ILLiad Resource Sharing Management software. Verify the information for your article is correct (e.g. author, publication year, title, DOI), and your submitted request will be fulfilled by a librarian contacting a librarian at another school who pays for access to that article. Within a few business hours, you should receive an email from ILLiad that your inter-library loan item is ready. You will be able to download the PDF directly from that link. Thank your university librarians when you get a chance!

Open access

You might wonder why access to scientific information is not guaranteed to all. Models of evidence-based practice treat assume that access is frictionless, but students quickly find out that getting access to the full-text is not easy. To secure the human right to research, a global social movement has emerged: open access. Articles published open access (OA) are available without a paywall to anyone with an internet connection. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) provides the canonical definition of open access. A publication is considered open access if it meets three criteria:

- its content is universally and freely accessible, at no cost to the reader, via the Internet or otherwise

- the author or copyright owner irrevocably grants to all users, for an unlimited period, the right to use, copy, or distribute the article, on condition that proper attribution is given

- it is deposited, immediately, in full and in a suitable electronic form, in at least one widely and internationally recognized open access repository committed to open access (UNESCO, n.d.).

Open access, in short, means free to anyone with an internet connection.

Scientific publication: A public good

An internet-enabled movement, OA emerged as global interconnection drove the cost for distributing scientific information to near zero. The 2002 Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI) presciently noted that publishing one’s results without payment produced a public good–a scientific information commons that could be accessed by anyone with an internet connection. The thousands of BOAI signatory nations and organizations agree that “removing access barriers to this literature will accelerate research, enrich education, share the learning of the rich with the poor and the poor with the rich, make this literature as useful as it can be, and lay the foundation for uniting humanity in a common intellectual conversation and quest for knowledge” (BOAI, 2002).

Why is the United Nations involved in open access journal publication? For better or worse, the academic journal article has become a valuable commodity in the Internet-facilitated global knowledge economy. Being able to access the latest advances in healthcare, technology, and other domains is necessary for developing countries, but paywalls stand in the way of using science-informed social development as well as evidence-based practices in health and social care.

According to UNESCO, “scientific information is both a researcher’s greatest output and technological innovation’s most important resource.” UNESCO views open access to scientific journal articles and other data as not merely one option for publishing, but a human rights movement, “building peaceful, democratic and inclusive knowledge societies,” through “universal access to information,” needed to fully participate in the global knowledge economy from which many are currently excluded.

Open access is one component of the broader open science movement, whose insights are woven throughout this book. Sharing data, tools, and power across societies progresses the knowledge-creation capacity of the global scientific community (UNESCO, 2023). Developing countries lack access to the (English-dominant) scientific literature, furthering the exclusion of groups and ideas from nondominant cultures. When they are able to publish, paywalls inhibit people in their country, or anyone aside from university-affiliated researchers in well-funded libraries, from accessing their scientific research products.

Publishing oligopoly: Enclosing public goods behind a paywall

Open Access can be confusing to researchers because, I believe, implicitly we think open access should be the norm. It is not. According to Pendell (2018), 48% of social work articles were available open access. When I re-ran the study with Anne-Marie Gruber in 2023, we found similar results, unless the researcher accessed illicit pirate repositories. the public good of social work scientific publication has been enclosed at exorbitant prices for the standard copyright term: the author’s life, plus 70 years.

Many social work organizations have partnered with for-profit publishers monopolizing social work knowledge. Just five for-profit publishers own 70% of social science journal articles (Lariviere et al., 2015) a proportion which has only increased in recent years (Hansen et al., 2024). Oligopolies exist to maximize profits. Gross profit margins for Elsevier and Wiley were 64.9% and 70.6% respectively (RELX Group PLC, 2023; John Wiley & Sons, 2024) similar to, or sometimes even exceeding, that of companies such as Google or Meta.

Despite ethical commitments to sharing knowledge for evidence-based practice, we trust publishers who sell our data to the Department of Homeland Security (SPARC, YEAR). Because online interconnectivity brought the price of publishing and sharing information down to near-zero, publishers have adapted to business models that combine enduring copyright monopolies and surveillance capitalism. As open access advanced, publishers adapted by introducing fees to make articles open access. Between 2019 and 2023, major publishers extracted $8.968 billion (in 2023 U.S. dollars) from article processing charges (APC) alone, which removed subscription requirements on less than one quarter of journal articles (Haustein et al., 2024).

The prices you see for individual journal articles, ranging from a dozen to hundreds of dollars, are as ridiculous as they appear. You do not need to pay them. Understanding open access is necessary to get to the full-text of nearly all journal articles at zero cost.

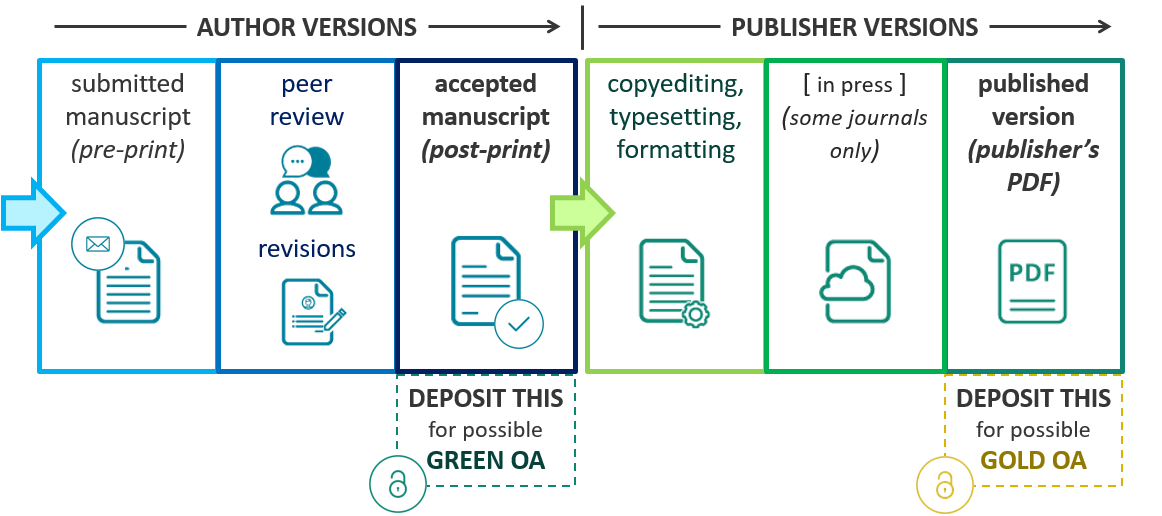

A confusing array of colors

The confusing landscape of article access is caused by the monopoly and surveillance capitalism. To simplify things, librarians developed a color-based system of open access classifications, as shown in Figure 1. To properly conduct scientific inquiry, you should be able to recognize each color. Practitioners will want to share articles and create new resources with them, so the next section will he next section will walk through each color of the OA rainbow, reviewing the boundaries of copyright law as well as the rights that practitioners, students, and others retain with open access publication. Some of the colors are not in Figure 1 because they violate copyright law.

Figure 1: Colors of Open Access Colors

Diamond OA: Free for authors & readers

Diamond OA (a.k.a platinum OA) is the best system because readers and authors do not face a paywall. Instead, the costs of editing the journal are sponsored by an organization or government body. For example, Advances in Social Work is published by Indiana University and supported by public funds. In return, it produces a public good: free social work scholarship.

Social work has lagged behind other disciplines in adopting open access publishing models, but there are many examples of Diamond OA journals provide fee-free open access for both authors and readers. The most prestigious of these journals is Advances in Social Work, but there are many others including Social Work & Society and Abolitionist Perspectives in Social Work. Publishing in these journals allows authors to retain copyright ownership of their work.

Articles are licensed under a creative commons attribution license (CC-BY). The CC BY license allows readers to retain and republish a copy, repurpose contents with attribution to the original authors, and access articles immediately with no cost as long as they have an internet connection. For example, a clinician could create an informational pamphlet with extensive use of the content of an journal article or record a podcast for community members reading from sections of a journal article licensed using CC-BY, as long as one attributed the knowledge to its original author. Such transformative use is not possible for articles in Critical Social Work which only allow one to retain and copy and share it with others (CC BY NC ND Citation?). No derivative works or profit is allowed.

Bronze OA: Free for authors & readers, with limitations

Although there are few Diamond OA journals in social work, sharing social work scholarship for free on the internet is not a new practice. Bronze OA is an established practice in social work journal publication. Some journals in social work have provided free online access to their articles and do not charge authors an APC. Because these articles carry a traditional copyright license that does not permit one to share the article with others or create derivative works, Bronze OA is less effective at achieving the goal of open access for social good than Diamond OA. Regardless, Bronze OA journals should be commended for sharing information without a paywall to anyone with an internet connection.

Bronze OA journals are often affiliated with academic institutions like the Journal of Applied Learning in Social Work Education (formerly, Field Educator) published by the Simmons School of Social Work, Critical Social Work published by the University of Windsor, the Columbia Social Work Review of social work student scholarship published by the Columbia University School of Social Work, and the Journal of Social Work Values & Ethics published by the International Federation of Social Workers. Licensing is often difficult to judge and can change over time. The Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare imposes a paywall for two years but then provides free access to journal articles under a traditional copyright license. The Journal of Nephrology Social Work, published by the Council of Nephrology Social Workers of the National Kidney Foundation, appears to be freely available but article usage rights vary by year.

Bronze OA is still on the winners board for open access, but it’s in third place because its licensing terms are ambiguous. Bronze OA journals often rely on traditional copyright licenses which restricts how their articles may be redistributed and used. Under the terms of traditional copyright, readers cannot legally redistribute articles to trainees, colleagues, or clients. Sharing a PDF of a journal article is piracy without an open license permitting redistribution. Of course, the beauty of Bronze OA is that the full-text is available to everyone from the publisher, so one could easily share a link. That single point of access can change over time, introducing a potential point of failure. There is nothing stopping that publisher from revoking free access at any time, and online archives cannot host a copy because redistribution violates traditional copyright licenses.

Access is only one component of evidence-based practice. As a social worker transitions from research consumption to communication, they would be unable to adapt chunks of copyrighted content in a Bronze OA journal article into a pamphlet for office distribution or video abstract for Instagram without running afoul of copyright law. The creative commons attribution license and other open licenses simplify the legal permissions for scientific communication in evidence-based practice.

Gold OA: Authors must pay for OA, free to readers

All articles in a Gold OA journal are open access, and readers can access them freely. Unlike Diamond OA and Bronze OA, authors who are accepted to Gold OA journals must pay a very expensive APC. Gold OA is relatively uncommon, as 70% of journals in the Directory of Open Access Journals do not charge APCs (Morrison, 2022, p. 1797). Researchers publishing articles in Health & Social Care in the Community must pay the $2700 APC for Wiley’s Open Access publication system. This is the only gold OA journal in social work, to my knowledge. In Gold OA journals, authors retain ownership of their scholarly work. Instead of signing over their copyright to the publisher, Gold OA journals must use a CC-BY license that permits transformative reuse by readers.

Hybrid OA: If authors pay for OA, free to readers

While it would be more objective for me to state that Hybrid OA is a debated type of open access, I am of the opinion that Hybrid OA is not actually a type of open access. It is a way to protect publisher profits and undermine the open access movement. Hybrid OA is an example of openwashing, or the wrapping of inequitable and extractive practices in language from open access and affiliated movements.

That is a shame because the overwhelming majority of social science journals and almost all top-tier social work journals are are hybrid OA journals. In other words, most social work journals are paywalled journals for readers and free for authors to publish. However, the author can pay a $2,000-$5,000 APC to remove the paywall. The exorbitant cost is why you will only see a few articles available for free in each issue of the journal. By associating OA with the highway robbery prices of APCs, for-profit journal publishers associate extractive practices with the open access movement.

In hybrid OA journals, the publisher often retains full ownership of the Version of Record, which may be both physically printed and published on the journal’s website. The existence of established and reputable Diamond and Bronze OA journals that do not rely on partnerships with commercial journal publishers calls into question the social work profession’s reliance on paywall profiteers to achieve the human right to research. Professional associations misguidedly partner with commercial publishers to secure the right to evidence-based practice. The resulting information inequities impact our ability to address client and community problems. The techniques in this chapter will help you fill in the OA leadership gaps for your evidence-based practice literature reviews.

Green OA: Author self-archiving, free to readers

Thus far, we have focused on getting the PDF from the publisher, but that is not the only legal source for the full-text of journal articles. Across multiple studies, only about 25% of social work journal articles are open access from the publisher. Fortunately, another quarter of journal articles are accessible because authors have made them available on their personal website, academic social network, university or disciplinary repository, or other website–Green OA. According to Barnes (2018), green OA is when:

A version of the publication is archived online, e.g. in a repository. It does not include any of the work typically carried out by the publisher, such as e.g. copyediting, proofreading, typesetting, indexing, metadata tagging, marketing or distribution. It is usually not listed on the publisher’s website. It can be freely accessed but sometimes only after an embargo period, and there can be barriers to reuse. The author usually does not retain the copyright. (para. 5)

Green OA is explicitly allowed by almost all publisher’s open access policies. Open science advocates outside of social work demanded these reforms. Despite nearly all Hybrid OA journals offering Green OA alternatives fewer researchers and academics are aware of Green OA vs. Hybrid OA options. Publishers heavily advertise Hybrid OA because it is a lucrative revenue stream, while Green OA is free for authors and readers, driving web traffic to pages not owned by the publisher. For obvious reasons, Green OA is not mentioned during the publication process at a typical journal.

Another reason that faculty and researchers have been slower to pick up on Green OA is that the version or formatting of the article might appear differently than the one from the publisher. The accepted manuscript may be a word processing document or PDF document, but it will look like the papers you write. When speaking to researchers, I often say that the accepted manuscript is the last Word document you send to the publisher. Social workers must learn to distinguish between the submitted manuscript, which has not yet been peer reviewed, from the accepted manuscript, which has been peer reviewed but not typeset for publication. Fortunately, the title page of a manuscript should contain its status in peer review (unreviewed, in review, rejected, etc.).

The full-text of journal articles go through multiple versions as they proceed through publication. As Figure 2 demonstrates how green OA enables authors to deposit their peer reviewed manuscript and into an online repository.

Green OA is possible because the underlying scholarship is the author’s intellectual property. Thus, the accepted manuscript can be shared by the author in places other than the publisher’s website.

Though it does not cost any money, Green OA is more work for authors, and many lack knowledge about their rights to share via Green OA. Each journal requires authors to include language about where the version of record can be found as well as licenses that restrict commercial and derivative reuse. In addition to setting more restrictive license terms, publishers often impose an an embargo period under which the publisher restricts how and where the authors are legally allowed to share their work. This is why finding journal articles from the past two years is more difficult than those past their embargo period of a year or two.

Publishers also create different policies for different repositories. For example, Social Work Research, published by Oxford University Press, allows authors to share their submitted manuscript (before peer review) on any website, their accepted manuscript immediately on their personal website, and after two years, the accepted manuscript can be shared on a subject or institutional repository like SocArXiv, Zenodo, or a university repository. By contrast, the Journal of Social Work, published by Sage, sets a lenient policy. It does not impose an embargo or specify which repositories are allowed for authors to share their accepted manuscript.

Fortunately, Google Scholar crawls the web and indexes articles shared via Green OA. Click on the “all # versions” link to view each web location for the article. Even if the PDF is not visible on this page, click through to each repository since Google Scholar does not perfectly surface all PDFs on its search results page. Yes, I realize this is tedious, but I did it for 500 articles with my colleague last year, and I’m here to tell you you’ll miss a few PDFs if you don’t do this.

Green OA is wonderful, but because of the restrictions imposed by commercial publishers, it is unable to surface more than a quarter of the social work literature. Comparing Pendell’s 2018 data and DeCarlo & Gruber’s 2023 data, more researchers take advantage of Green OA. Governments and foundations are increasingly requiring OA as a condition of funding, and Green OA provides a researchers a no-cost option to fulfill that requirement.

Gray OA: Academic social networks, free to readers

There are other websites on the internet that host journal articles besides university and noncommercial repositories. Although they are technically termed an academic social networking sites, they are not used like Bluesky or Instagram. Instead, ResearchGate and Academia.edu are effectively repositories of journal articles (and other scholarly materials). In our recent study, social work scholarship was far more heavily represented in ResearchGate than Academia.edu. Unlike the noncommercial and university repositories, these websites monetize your information and attention.

Gray OA repositories operate in a legal gray area because they host a large body of materials uploaded by users in violation of copyright terms set by publishers. In 2017, publishers sued ResearchGate for hosting pirated materials, but this was settled in 2024. Now, ResearchGate and Academia.edu are specifically allowed in publisher’s open access policies. Since 2021, Wiley has partnered with ResearchGate to distribute the Version of Record of journal articles for hundreds of journals. Funny enough, this means many researchers have ResearchGate profiles with users accessing their articles without them opening the website at all! (https://www.researchgate.net/publisher-solutions-blog/how-wileys-expanded-partnership-with-researchgate-benefits-authors)

Google Scholar also indexes Gray OA articles. If you are searching for articles from the past two or three years, you should also search on ResearchGate. Google Scholar does not perfectly index ResearchGate, and in our study, we found it necessary to search both locations to find the full-text of sampled articles.

Although not an academic social network, one archive that comes up often is the Internet Archive’s Archive.org. It is not social media and authors do not upload directly to it. Is collections appear to be mirrors of other open collections, but it is certainly safe to download from here. That is not necessarily the case for all websites!

Pirate OA: Steal this PDF

Gray OA repositories are sustained by ad revenue and partnerships with commercial publishers. Pirate OA (a.k.a Black OA) repositories are founded on the communist idea that scientific knowledge is a public good that cannot be owned by a person or company. The most commonly accepted term for the illegal repositories of copyrighted journal articles shared via Pirate OA is shadow libraries. Although there are many shadow libraries with relevant social work scholarship, the most important is Sci-Hub. Pirate OA is also available for periodicals like newspapers and magazines. Archive.today is a Pirate OA project that focuses, in part, on archiving news articles without a paywall. The Internet Archive also hosts a repository of archived webpages.

Sci-Hub provides access to about 85% of all paywalled journal articles, a collection more robust than the ivy-league University of Pennsylvania library (Himmelstein et al., 2018). In our study of social work journal articles, I was the designated pirate and successfully accessed 80% of articles in the sample via Sci-Hub. You might assume that Sci-Hub has everything that other repositories have, and weirdly enough, that is incorrect. Sci-Hub does not perfectly copy all of the materials on ResearchGate or Google Scholar. Searching all three (ResearchGate, Google Scholar, and Sci-Hub) was necessary to get access to the roughly 90% of social work journal articles available on the internet without a paywall.

Because it ignores copyright law, Sci-Hub uses a simple interface in which the user inputs the digital object identifier (DOI) or the website address for the publisher’s version of the article. If Sci-Hub has the article, the PDF will appear immediately. If Sci-Hub does not have the article, Z-Library is the next step. Students may be familiar with Z-library as it hosts a large collection of pirated textbooks. Z-Library’s collection of journal articles is more comprehensive than Sci-Hub, but it does not have as many recent articles from those journals. Z-library requires a login to download content. In our study of recent journal articles, we found that the collections from the shadow libraries Library Genesis and Anna’s Archive to be an incomplete copy of Sci-Hub’s collection. These results may vary over time as shadow libraries uses illicit acquisition methods.

Another problem with violating copyright law is that the web domains for Sci-Hub and other shadow libraries get seized or blocked by governments enforcing copyright laws. So, shadow libraries need to change their website address periodically. Scammers set up decoy websites to lure unsuspecting students and infect their computers with malware. How would you know whether to visit sci-hub.se versus sci-hub.st? A good practice is to search Reddit for the shadow library you are trying to access and look at the Wiki for current, safe web addresses.

It remains an ethical dilemma for social workers whether to engage with Sci-Hub and other shadow libraries. On the one hand, these repositories violate copyright law and do not remunerate the owners of that information. On the other hand, scientific information is a public good and the paywalls erected by commercial publishers render evidence-based practice impossible for those unaffiliated with a well-funded university in the developed world. Clients have a right to evidence-based care, and social workers should not face dilemmas in accessing scholarly materials to inform care.

It should not require copyright infringement to conduct scientific research. Sci-Hub is a symptom of a broken system of scholarly publication that locks away journal articles behind impossibly high paywalls. Accessing the number of articles necessary for a competent literature review would costs thousands of dollars. Fortunately, there is a big, gaping hole in the paywall big enough for everyone to fit through! Without Pirate OA, most of the world would be unable to access half of the scientific literature offered by licit alternatives.

Accessing journal articles after graduation

Paywalls effectively shut out social work students from accessing about half of journal articles after they graduate. After a year or so, your login will no longer work with the library. It’s sincerely too expensive for your university to afford lifetime access to journal articles for all graduates, though it is certainly understandable why students would expect differently.

Without a university library login, getting a PDF of a journal article becomes more challenging. You can subscribe to journals yourself, and many practitioners do that. However, you can always ask an author for a copy of their article. They will usually send it to you.

Consider this advice adapted from the brilliant librarians at Virginia Tech on getting through paywalls:

- Check Google Scholar for alternative versions of the article you are trying to access. On the bottom right of each source in Google Scholar results is a link that says “all # versions.” If the author has uploaded an open access version of their work, you may need to click this link to get to a free copy rather than the paywalled copy at the journal.

- Conduct a search for the article in a normal Google search (possibly adding “.pdf” to the query) to see if you can find a copy of the article without a paywall.

- Go to ResearchGate and search for the article. Google Scholar does not perfectly index ResearchGate.

- Email the author for a copy. Be sure to Google search for their current institution and contact information. Academics often move from school to school.

- Go to unpaywall.org and install the Unpaywall extension for Firefox and Chrome. Once installed, a green icon of an open lock will appear on any scholarly resource for which there is a publicly accessible version without a paywall.

- Go to oahelper.org and install their desktop or mobile app to search for unpaywalled and open access versions of publications.

Key Takeaways

- Most social work journal articles are published behind a paywall. There are relatively few OA journals in social work.

- OA journal articles are free to readers, but they are not necessarily free for researchers to publish.

- Researchers can share their work with readers for free using Green OA and Gray OA, but the licensing terms can be confusing.

- To access a journal article without cost, social workers should search Google Scholar and ResearchGate.

- Sci-Hub hosts about 80% of social work journal articles.

Exercises

- Look up your professor’s publications, and see if they can share anything as Green OA that’s missing. I have one still hanging, for the record. Use the Open Policy Finder (https://openpolicyfinder.jisc.ac.uk/) tool to check each journal your professor has submitted to and instruct them how they can make their works OA today!

- Develop your post-university article access skills. Open a private browsing window with nothing logged in, and see if you can access a few articles from your literature review without cost.

4.3 Critical information literacy

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Distinguish between information literacy and critical information literacy

- Define information privilege and discuss how it impacts practitioners, global researchers, and client populations.

- Articulate a human rights based

Ultimately, searching and reviewing the literature will be one of the most transferable skills from your research methods classes. All social workers have to consume research information as part of their jobs. In this section, we hope to ground this orientation toward scientific literature in your identity as a social worker, scholar, and social scientist.

Critical information literacy

The core skill you are developing in Chapters 3-5 of this textbook is information literacy, or “a set of abilities requiring individuals to ‘recognize when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (American Library Association, 2020).[7] Information literacy is key to the lifelong learning process of social work practice, as you will have to continue to absorb new information after you leave school and progress as a social work practitioner. In the evidence-based practice process, information literacy is a key component in helping clients and communities achieve their goals.

However, social work researchers and librarians dedicated to social change embrace a more progressive conceptualization of this skill called critical information literacy. It is not enough to simply know how to use the tools we use to share knowledge. Instead, social work researchers should critically examine “the social, political, economic, and corporate systems that have power and influence over information production, dissemination, access, and consumption” (Gregory & Higgins, 2013, p. ix).[8] Just like all other social structures, those we use to create and share scientific knowledge are subject to the same oppressive forces we encounter in everyday life—racism, sexism, classism, and so forth. Critical information literacy combines both fine-tuned skills for finding and evaluating literature as well as an understanding of the cultural forces of oppression and domination that structure the availability of information. As Tewell (2016)[9] argues, “critical information literacy is an attempt to render visible the complex workings of information so that we may identify and act upon the power structures that shape our lives” (para. 6).

Information privilege & the right to research

One way to apply critical information literacy is by leveraging your information privilege. Grounded in critical librarianship, information privilege is defined by Booth (2017)[10] as:

the accumulation of special rights and advantages not available to others in the area of information access. Individuals with the resources to access the information they need, are affiliated with research or academic institutions and libraries, or live close to a public library with access to resources and services such as free interlibrary loan are examples of those with information privilege. Those who are unable to access the information they need are information underprivileged or impoverished [emphasis in original]; this includes people who are incarcerated, poor, unaffiliated with a university or research institution, or live in rural areas distant from a public library.

How can you recognize information privilege? The video from the Steely Library at Northern Kentucky University below will help you.

The current model of scientific publishing privileges those already advantaged and raises important obstacles for those in oppressed groups to access and contribute to scientific knowledge or research-informed social change initiatives. For a more thorough, Black feminist perspective on scholarly publication see Eaves (2020).[11] As social workers, it is your responsibility to use your information privilege—the access you have right now to the world’s knowledge and the skills you gain during your graduate education and post-graduate professional development—to fight for social change.

As Willinsky (2006) states, “access to knowledge is a human right that is closely associated with the ability to defend, as well as to advocate for, other rights.” The open access movement is a human rights movement that seeks to secure the universal right to freely access information in order to produce social change. Information is a resource, and the current approach to sharing that resource—the key to human development—excludes many oppressed groups from accessing what they need to address matters of social justice. Appadurai (2006)[12] conceptualizes this as a “right to research…the right to the tools through which any citizen can systematically increase that stock of knowledge which they consider most vital to their survival as human beings and to their claims as citizens” (p. 168). From a human rights perspective, research is not something confined to professional researchers but “the capacity to systematically increase the horizons of one’s current knowledge, in relation to some task, goal or aspiration” (p. 173).

One of the reasons why research feels very remote to social workers is a lack of supportive information environments. Many of you have likely heard of the invisible knapsack of privilege. Extending this concept to information privilege, the Duke University Library’s combined both frameworks into the invisible knapsack of information privilege. Even if we provided perfectly free access to scientific information, investments in the educational, technological, and basic needs security of students are necessary to make good use of scientific knowledge.

Using your critical information literacy

It is important to recognize your own information privilege and use it to help enact social change on behalf of those who are oppressed within the system of scholarly knowledge production and sharing we currently have. We previously discussed the issue of paywalls in this chapter. Paywalls lock away access to knowledge to only those who can afford to pay, shutting out those with fewer resources. In addition to researchers and practitioners, paywalls also shut out community members, clients, and self-advocates from accessing the research information they need to effectively advocate for themselves. This is because paywalls are an obstruction to the basic human right to access and interact with the knowledge humanity creates.

In Chapter 2, we discussed action research which includes community members as part of the research team. Action research addresses information privilege by addressing the power imbalance between academic researchers and community members, ensuring that the voice of the community is represented throughout the process of creating scientific knowledge. This equity-enhancing process provides community members with access to scientific knowledge in many ways: (1) access via academic to scholarly databases, (2) access to the training and human capital of the researcher, who embodies years of education in how to conduct social science research, and (3) access to the specialized resources like statistical or qualitative data analysis software required to conduct scientific research.

Moreover, it highlights that while open access is important, it is only one half of the equation. Open access only addresses how people receive scholarly information. But what about how social science knowledge is created? Action research underscores that equity is not just about accessing scientific knowledge, but co-creating scientific knowledge as partners with community members. Critical information literacy critiques the current practices of scientific inquiry in social work and other disciplines as exclusionary, as they reinforce existing sources of privilege and oppression.

This imbalance between academic researchers and community members should be considered within an English-speaking, Western context. The widespread adoption of open access and open science in the developing world underscores the extreme imbalances that international researchers face in accessing scholarly information (Arunachalam, 2017).[13] Paywalls, barriers to international travel, and the tradition of in-person physical conferences structure the information sharing practices in social science in a manner that excludes participation from researchers who lack the financial and practical resources to access these exclusionary spaces (Bali & Caines, 2016; Eaves, 2020).[14]

Social work often involves accessing, creating, and otherwise engaging with social science knowledge to create change. On the micro-level, critical information literacy is needed to inform evidence-based decision-making in clinical practice. On the meso- and macro-level, social workers can use information literacy skills to give a voice for community concerns, help communities access and create the knowledge they need to foster change, or evaluate how well existing programs serving the community achieve their goals. Now that you are familiar with how to conduct ethical and responsible research and how to read the results of others’ research, you have an obligation to use your information literacy skills to create social change. This is part of critical information literacy: using your information privilege to address social injustices.

Information literacy beyond scholarly literature

The research process we described in this chapter will help you arrive at an understanding of the scientific literature. However, that is not the only literature of value for researchers. For those conducting action research that engages more with communities and target populations, researchers are responsible not only for reviewing the scientific literature on their topic but also the literature that communities find important. If there are local newspapers, television shows, religious services or events, community meetings, or other sources of knowledge that your target population finds important, you should engage with those resources as well. Understanding these information sources builds empathetic understanding of participating groups and can help inform your research study. Moreover, they are likely to contain knowledge that is not a part of the scientific literature but is nevertheless crucial for conducting scientific research appropriately and effectively in a community.

Key Takeaways

- At this point, you should have a folder full of articles (at least a few dozen) that are relevant to your topic. Don’t worry! You won’t read all of them, but you will skim most of them for the most important information.

- Social workers should develop critical information literacy. This helps social workers use social science knowledge for social change, and it critiques how current publishing models exclude and privilege different groups from accessing and creating knowledge.

- Social work involves helping others understand social science and applying it in your practice. You must learn how to discriminate between reliable and unreliable information and apply your scientific knowledge to benefit your clients and community.

Exercises

- Write a few sentences about what you think the answer to your working question might be.

- Identify at least five reputable sources of information from your literature search that provide evidence that what you wrote is true.

- What steps do you plan to take to demonstrate that you are helping others to understand social science and its relationship to your practice?

4.4 Synthesizing information across sources

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Use summary tables to organize information from empirical articles

- Organize information from the literature reviews of articles you read into a topical outline

- Create a concept map that visualizes the key concepts and relationships relevant to your working question

- Use what you learn in the literature search to revise your working question

In this chapter, we’ve reviewed how to access the full text of journal articles and evaluate them for inclusion in your literature review. This final section will add to your critical information literacy skills by helping you extract information from scientific literature reviews.

Read literature reviews

At the beginning of a research project, you don’t know a lot about your research topic. You don’t even know what you don’t know! That’s why it’s a good idea to get a broad, birds-eye view of the literature by looking at other literature reviews. Someone has gone through the trouble of reading a few dozen sources and telling you what’s important about them. Get a broad sense of the literature and follow up on subtopics that interest you. As we discussed in Chapter 3, review articles are useful because they synthesize all the information on a given topic. By reading what another researcher thinks about the literature, you can get a more wide-ranging sense of it than reading the results of only one study.

Rview articles will often have “literature review,” “systematic review,” or other similar terms in the title. These articles are 100% literature review. The author’s primary goal is to present a comprehensive and authoritative view of the important research in a particular topic area. Think of these as a way to engage with dozens of articles at the same time, and you can find a lot of relevant references from reading the article. For the same reason, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses are also excellent sources as you are starting a literature review.

Unfortunately, review articles do not exist for every topic. If you are unable to find a review article, try to find an empirical article that has a lengthy literature review. You are mostly reading to see what the author says about the literature on your topic in the introduction and discussion sections. Once you identify the article as highly relevant to your working question, you can use the author’s references to inform your search. You will get a lot out of reading what other researchers think about the literature.

Copy facts into an outline

As you read an article in detail, I suggest copying any facts you find relevant in a separate word processing document. Copying and pasting from PDF to Word can be difficult because PDFs are image files, not documents. Fortunately, Zotero’s PDF reader removes invisible characters from most content. If that fails, use the HTML version of the article on the publisher’s website (if available). One could also convert the PDF to Word in a PDF editor or use the “paste special” command to paste PDF content into Word without formatting. If it’s an old PDF, you may have to simply type out the information you need or take a screenshot. It can be a messy job, but having all of your facts in one place is very helpful when drafting your literature review.

You should copy and paste any fact or argument you consider important. Some good examples include definitions of concepts, statistics about the size of the social problem, and empirical evidence about the key variables in the research question, among countless others. It’s a good idea to consult with your professor and the course syllabus to understand what they are looking for when reading your literature review. Facts for your literature review are principally found in the introduction, results, and discussion section of an empirical article or at any point in a non-empirical article. Copy and paste into your notes anything you may want to use in your literature review.

Importantly, you must make sure you note the original source of each bit of information you copy. Nothing is worse than needing to track down a source for fact you read who-knows-where. If you found a statistic that the author used in the introduction, it almost certainly came from another source that the author cited in a footnote or internal citation. You will want to check the original source to make sure the author represented the information correctly. Moreover, you may want to read the original study to learn more about your topic and discover other sources relevant to your inquiry.

Combine fact outlines into a topical outline

Assuming you have pulled all of the facts out of multiple articles, it’s time to start thinking about how these pieces of information relate to each other. Start grouping each fact into categories and subcategories as shown in Table 5.2. For example, a statistic stating that single adults who are homeless are more likely to be male may fit into a category of gender and homelessness. For each topic or subtopic you identify during your critical analysis of each paper, determine what those papers have in common. Likewise, determine which differ. If there are contradictory findings, you may be able to identify methodological or theoretical differences that could account for these contradictions. For example, one study may sample only high-income earners or those living in a rural area. Determine what general conclusions you can report about the topic or subtopic, based on all of the information you’ve found.

Create a separate document containing a topical outline that combines your facts from each source and organizes them by topic or category. As you include more facts and more sources in your topical outline, you will begin to see how each fact fits into a category and how categories are related to one another. Keep in mind that your category names may change over time, as may their definitions. This is a natural reflection of the learning you are doing.

| Fact outline | Topical outline |

|

|

The short video (8 minutes) walks students through the process of creating a fact outline and topical outline.

Reassess strengths and gaps in your knowledge

A complete topical outline is a long list of facts arranged by category. As you step back from the outline, you should assess which topic areas for which you have enough research support to allow you to draw strong conclusions. You should also assess which areas you need to do more research in before you can write a robust literature review. The topical outline should serve as a transitional document between the notes you write on each source and the literature review you submit to your professor.

It is important to note that they contain plagiarized information that is copied and pasted directly from the primary sources. In this case, it is not problematic because these are just notes and are not meant to be turned in as your own ideas. For your final literature review, you must paraphrase these sources to avoid plagiarism. More importantly, you should keep your voice and ideas front-and-center in what you write as this is your analysis of the literature. Make strong claims and support them thoroughly using facts you found in the literature. We will pick up the task of writing your literature review in a future chapter.

Revise your working question

You should be revisiting your working question throughout the literature review process. As you continue to learn more about your topic, your question will become more specific and clearly worded. This is normal, and there is no way to shorten this process. Keep revising your question in order to ensure it will contribute something new to the literature on your topic, is relevant to your target population, and is feasible for you to conduct as a student project.

For example, perhaps your initial idea or interest is how to prevent obesity. After an initial search of the relevant literature, you realize the topic of obesity is too broad to adequately cover in the time you have to do your project. You decide to narrow your focus to causes of childhood obesity. After reading some articles on childhood obesity, you further narrow your search to the influence of family risk factors on overweight children. A potential research question might then be, “What maternal factors are associated with toddler obesity in the United States?” You would then need to return to the literature to find more specific studies related to the variables in this question (e.g. maternal factors, toddler, obesity, toddler obesity).

Similarly, after an initial literature search for a broad topic such as school performance or grades, examples of a narrow research question might be:

- “To what extent does parental involvement in children’s education relate to school performance over the course of the early grades?”

- “Do parental involvement levels differ by family social, demographic, and contextual characteristics?”

- “What forms of parent involvement are most highly correlated with children’s outcomes? What factors might influence the extent of parental involvement?” (Early Childhood Longitudinal Program, 2011).[15]

In either case, your literature search, working question, and understanding of the topic are constantly changing as your knowledge of the topic deepens. A literature review is an iterative process, one that stops, starts, and loops back on itself multiple times before completion. As research is a practice behavior of social workers, you should apply the same type of critical reflection to your inquiry as you would to your clinical or macro practice.

Key Takeaways

- You won’t read every article all the way through. For most articles, reading the abstract, introduction, and conclusion are enough to determine its relevance. It’s expected that you skim or search for relevant sections of each article without reading the whole thing.

- For articles where everything seems relevant, use a summary table to keep track of details. These are particularly helpful with empirical articles.

- For articles with literature review content relevant to your topic, copy any relevant information into a topical outline, along with the original source of that information.

- Use a concept map to help you visualize the key concepts in your topic area and the relationships between them.

- Revise your working question regularly. As you do, you will likely need to revise your search queries and include new articles.

Exercises

- In your folder full of article PDFs, look for the most relevant review articles. If you don’t have any, try to look for some. If there are none in your topic area, you can also use other non-empirical articles or empirical articles with long literature reviews (in the introduction and discussion sections).

- Create a word processing document for your topical outline and save it in your project folder on your hard drive. Using a review article, start copying facts you identified as Background Information or Results into your topical outline. Try to organize each fact by topic or theme. Make sure to copy the internal citation for the original source of each fact. For articles that do not use internal citations, create one using the information in the footnotes and references. As you finalize your research question over the next few weeks, skim the literature reviews of the articles you download for key facts and copy them into your topical outline.

- Look back at the working question for your topic and consider any necessary revisions. It is important that questions become clearer and more specific over time. It is also common that your working question shift over time, sometimes drastically, as you explore new lines of inquiry in the literature. Return to your working question regularly and make sure it reflects the focus of your inquiry. You will continue to revise your working question until we formalize it into a research question at the end of Part 2 of this textbook.

- Bendavid, E., Mulaney, B., Sood, N., Shah, S., Ling, E., Bromley-Dulfano, R., ... & Tversky, D. (2020, April 17). COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. MedRxiv. ↵

- Joseph, A. (2020, June 4) ↵