8 Conceptualization in quantitative research

Chapter Outline

- Developing your theoretical framework

- Conceptual definitions

- Inductive & deductive reasoning

- Nomothetic causal explanations

Content warning: examples in this chapter include references to sexual harassment, domestic violence, gender-based violence, the child welfare system, substance use disorders, neonatal abstinence syndrome, child abuse, racism, and sexism.

8.1 Developing your theoretical framework

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Differentiate between theories that explain specific parts of the social world versus those that are more broad and sweeping in their conclusions

- Identify the theoretical perspectives that are relevant to your project and inform your thinking about it

- Define key concepts in your working question and develop a theoretical framework for how you understand your topic.

Theories provide a way of looking at the world and of understanding human interaction. Some theories try to explain the whole world, while others only try to explain a small part. Some theories can be grouped together based on common ideas but retain their own individual and unique features. Our goal is to help you find a theoretical framework that helps you understand your topic more deeply and answer your working question.

Theories: Big and small

In your human behavior and the social environment (HBSE) class, you were introduced to the major theoretical perspectives that are commonly used in social work. These are what we like to call big-T ‘T’heories. When you read about systems theory, you are actually reading a synthesis of decades of distinct, overlapping, and conflicting theories that can be broadly classified within systems theory. For example, within systems theory, some approaches focus more on family systems while others focus on environmental systems, though the core concepts remain similar.

Different theorists define concepts in their own way, and as a result, their theories may explore different relationships with those concepts. For example, Deci and Ryan’s (1985)[1] self-determination theory discusses motivation and establishes that it is contingent on meeting one’s needs for autonomy, competency, and relatedness. By contrast, ecological self-determination theory, as written by Abery & Stancliffe (1996),[2] argues that self-determination is the amount of control exercised by an individual over aspects of their lives they deem important across the micro, meso, and macro levels. If self-determination were an important concept in your study, you would need to figure out which of the many theories related to self-determination helps you address your working question.

Theories can provide a broad perspective on the key concepts and relationships in the world or more specific and applied concepts and perspectives. Table 7.2 summarizes two commonly used lists of big-T Theoretical perspectives in social work. See if you can locate some of the theories that might inform your project.

| Payne’s (2014)[3] practice theories | Hutchison’s (2014)[4] theoretical perspectives |

| Psychodynamic | Systems |

| Crisis and task-centered | Conflict |

| Cognitive-behavioral | Exchange and choice |

| Systems/ecological | Social constructionist |

| Macro practice/social development/social pedagogy | Psychodynamic |

| Strengths/solution/narrative | Developmental |

| Humanistic/existential/spiritual | Social behavioral |

| Critical | Humanistic |

| Feminist | |

| Anti-discriminatory/multi-cultural sensitivity |

Competing theoretical explanations

Within each area of specialization in social work, there are many other theories that aim to explain more specific types of interactions. For example, within the study of sexual harassment, different theories posit different explanations for why harassment occurs.

One theory, first developed by criminologists, is called routine activities theory. It posits that sexual harassment is most likely to occur when a workplace lacks unified groups and when potentially vulnerable targets and motivated offenders are both present (DeCoster, Estes, & Mueller, 1999).[5]

Other theories of sexual harassment, called relational theories, suggest that one’s existing relationships are the key to understanding why and how workplace sexual harassment occurs and how people will respond when it does occur (Morgan, 1999).[6] Relational theories focus on the power that different social relationships provide (e.g., married people who have supportive partners at home might be more likely than those who lack support at home to report sexual harassment when it occurs).

Finally, feminist theories of sexual harassment take a different stance. These theories posit that the organization of our current gender system, wherein those who are the most masculine have the most power, best explains the occurrence of workplace sexual harassment (MacKinnon, 1979).[7] As you might imagine, which theory a researcher uses to examine the topic of sexual harassment will shape the questions asked about harassment. It will also shape the explanations the researcher provides for why harassment occurs.

For a graduate student beginning their study of a new topic, it may be intimidating to learn that there are so many theories beyond what you’ve learned in your theory classes. What’s worse is that there is no central database of theories on your topic. However, as you review the literature in your area, you will learn more about the theories scientists have created to explain how your topic works in the real world. There are other good sources for theories, in addition to journal articles. Books often contain works of theoretical and philosophical importance that are beyond the scope of an academic journal. Do a search in your university library for books on your topic, and you are likely to find theorists talking about how to make sense of your topic. You don’t necessarily have to agree with the prevailing theories about your topic, but you do need to be aware of them so you can apply theoretical ideas to your project.

Applying big-T theories to your topic

The key to applying theories to your topic is learning the key concepts associated with that theory and the relationships between those concepts, or propositions. Again, your HBSE class should have prepared you with some of the most important concepts from the theoretical perspectives listed in Table 7.2. For example, the conflict perspective sees the world as divided into dominant and oppressed groups who engage in conflict over resources. If you were applying these theoretical ideas to your project, you would need to identify which groups in your project are considered dominant or oppressed groups, and which resources they were struggling over. This is a very general example. Challenge yourself to find small-t theories about your topic that will help you understand it in much greater detail and specificity. If you have chosen a topic that is relevant to your life and future practice, you will be doing valuable work shaping your ideas towards social work practice.

Integrating theory into your project can be easy, or it can take a bit more effort. Some people have a strong and explicit theoretical perspective that they carry with them at all times. For me, you’ll probably see my work drawing from exchange and choice, social constructionist, and critical theory. Maybe you have theoretical perspectives you naturally employ, like Afrocentric theory or person-centered practice. If so, that’s a great place to start since you might already be using that theory (even subconsciously) to inform your understanding of your topic. But if you aren’t aware of whether you are using a theoretical perspective when you think about your topic, try writing a paragraph off the top of your head or talking with a friend explaining what you think about that topic. Try matching it with some of the ideas from the broad theoretical perspectives from Table 7.2. This can ground you as you search for more specific theories. Some studies are designed to test whether theories apply the real world while others are designed to create new theories or variations on existing theories. Consider which feels more appropriate for your project and what you want to know.

Another way to easily identify the theories associated with your topic is to look at the concepts in your working question. Are these concepts commonly found in any of the theoretical perspectives in Table 7.2? Take a look at the Payne and Hutchison texts and see if any of those look like the concepts and relationships in your working question or if any of them match with how you think about your topic. Even if they don’t possess the exact same wording, similar theories can help serve as a starting point to finding other theories that can inform your project. Remember, HBSE textbooks will give you not only the broad statements of theories but also sources from specific theorists and sub-theories that might be more applicable to your topic. Skim the references and suggestions for further reading once you find something that applies well.

Exercises

Choose a theoretical perspective from Hutchison, Payne, or another theory textbook that is relevant to your project. Using their textbooks or other reputable sources, identify :

- At least five important concepts from the theory

- What relationships the theory establishes between these important concepts (e.g., as x increases, the y decreases)

- How you can use this theory to better understand the concepts and variables in your project?

Start to develop your own theoretical framework

Hutchison’s and Payne’s frameworks are helpful for surveying the whole body of literature relevant to social work, which is why they are so widely used. They are one framework, or way of thinking, about all of the theories social workers will encounter that are relevant to practice. Social work researchers should delve further and develop a theoretical or conceptual framework of their own based on their reading of the literature. In Chapter 8, we will develop your theoretical framework further, identifying the cause-and-effect relationships that answer your working question. Developing a theoretical framework is also instructive for revising and clarifying your working question and identifying concepts that serve as keywords for additional literature searching. The greater clarity you have with your theoretical perspective, the easier each subsequent step in the research process will be.

Getting acquainted with the important theoretical concepts in a new area can be challenging. While social work education provides a broad overview of social theory, you will find much greater fulfillment out of reading about the theories related to your topic area. We discussed some strategies for finding theoretical information in Chapter 3 as part of literature searching. To extend that conversation a bit, some strategies for searching for theories in the literature include:

- Using keywords like “theory,” “conceptual,” or “framework” in queries to better target the search at sources that talk about theory.

- Consider searching for these keywords in the title or abstract, specifically

- Looking at the references and cited by links within theoretical articles and textbooks

- Looking at books, edited volumes, and textbooks that discuss theory

- Talking with a scholar on your topic, or asking a professor if they can help connect you to someone

- Looking at how researchers use theory in their research projects

- Nice authors are clear about how they use theory to inform their research project, usually in the introduction and discussion section.

- Starting with a Big-T Theory and looking for sub-theories or specific theorists that directly address your topic area

- For example, from the broad umbrella of systems theory, you might pick out family systems theory if you want to understand the effectiveness of a family counseling program.

It’s important to remember that knowledge arises within disciplines, and that disciplines have different theoretical frameworks for explaining the same topic. While it is certainly important for the social work perspective to be a part of your analysis, social workers benefit from searching across disciplines to come to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. Reaching across disciplines can provide uncommon insights during conceptualization, and once the study is completed, a multidisciplinary researcher will be able to share results in a way that speaks to a variety of audiences. A study by An and colleagues (2015)[8] uses game theory from the discipline of economics to understand problems in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. In order to receive TANF benefits, mothers must cooperate with paternity and child support requirements unless they have “good cause,” as in cases of domestic violence, in which providing that information would put the mother at greater risk of violence. Game theory can help us understand how TANF recipients and caseworkers respond to the incentives in their environment, and highlight why the design of the “good cause” waiver program may not achieve its intended outcome of increasing access to benefits for survivors of family abuse.

Of course, there are natural limits on the depth with which student researchers can and should engage in a search for theory about their topic. At minimum, you should be able to draw connections across studies and be able to assess the relative importance of each theory within the literature. Just because you found one article applying your theory (like game theory, in our example above) does not mean it is important or often used in the domestic violence literature. Indeed, it would be much more common in the family violence literature to find psychological theories of trauma, feminist theories of power and control, and similar theoretical perspectives used to inform research projects rather than game theory, which is equally applicable to survivors of family violence as workers and bosses at a corporation. Consider using the Cited By feature to identify articles, books, and other sources of theoretical information that are seminal or well-cited in the literature. Similarly, by using the name of a theory in the keywords of a search query (along with keywords related to your topic), you can get a sense of how often the theory is used in your topic area. You should have a sense of what theories are commonly used to analyze your topic, even if you end up choosing a different one to inform your project.

Theories that are not cited or used as often are still immensely valuable. As we saw before with TANF and “good cause” waivers, using theories from other disciplines can produce uncommon insights and help you make a new contribution to the social work literature. Given the privileged position that the social work curriculum places on theories developed by white men, students may want to explore Afrocentricity as a social work practice theory (Pellebon, 2007)[9] or abolitionist social work (Jacobs et al., 2021)[10] when deciding on a theoretical framework for their research project that addresses concepts of racial justice. Start with your working question, and explain how each theory helps you answer your question. Some explanations are going to feel right, and some concepts will feel more salient to you than others. Keep in mind that this is an iterative process. Your theoretical framework will likely change as you continue to conceptualize your research project, revise your research question, and design your study.

By trying on many different theoretical explanations for your topic area, you can better clarify your own theoretical framework. Some of you may be fortunate enough to find theories that match perfectly with how you think about your topic, are used often in the literature, and are therefore relatively straightforward to apply. However, many of you may find that a combination of theoretical perspectives is most helpful for you to investigate your project. For example, maybe the group counseling program for which you are evaluating client outcomes draws from both motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. In order to understand the change happening in the client population, you would need to know each theory separately as well as how they work in tandem with one another. Because theoretical explanations and even the definitions of concepts are debated by scientists, it may be helpful to find a specific social scientist or group of scientists whose perspective on the topic you find matches with your understanding of the topic. Of course, it is also perfectly acceptable to develop your own theoretical framework, though you should be able to articulate how your framework fills a gap within the literature.

If you are adapting theoretical perspectives in your study, it is important to clarify the original authors’ definitions of each concept. Jabareen (2009)[11] offers that conceptual frameworks are not merely collections of concepts but, rather, constructs in which each concept plays an integral role.[12] A conceptual framework is a network of linked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. Each concept in a conceptual framework plays an ontological or epistemological role in the framework, and it is important to assess whether the concepts and relationships in your framework make sense together. As your framework takes shape, you will find yourself integrating and grouping together concepts, thinking about the most important or least important concepts, and how each concept is causally related to others.

Much like paradigm, theory plays a supporting role for the conceptualization of your research project. Recall the ice float from Figure 7.1. Theoretical explanations support the design and methods you use to answer your research question. In student projects that lack a theoretical framework, I often see the biases and errors in reasoning that we discussed in Chapter 1 that get in the way of good social science. That’s because theories mark which concepts are important, provide a framework for understanding them, and measure their interrelationships. If you are missing this foundation, you will operate on informal observation, messages from authority, and other forms of unsystematic and unscientific thinking we reviewed in Chapter 1.

Theory-informed inquiry is incredibly helpful for identifying key concepts and how to measure them in your research project, but there is a risk in aligning research too closely with theory. The theory-ladenness of facts and observations produced by social science research means that we may be making our ideas real through research. This is a potential source of confirmation bias in social science. Moreover, as Tan (2016)[13] demonstrates, social science often proceeds by adopting as true the perspective of Western and Global North countries, and cross-cultural research is often when ethnocentric and biased ideas are most visible. In her example, a researcher from the West studying teacher-centric classrooms in China that rely partially on rote memorization may view them as less advanced than student-centered classrooms developed in a Western country simply because of Western philosophical assumptions about the importance of individualism and self-determination. Developing a clear theoretical framework is a way to guard against biased research, and it will establish a firm foundation on which you will develop the design and methods for your study.

Key Takeaways

- Just as empirical evidence is important for conceptualizing a research project, so too are the key concepts and relationships identified by social work theory.

- Your social work theory textbook will provide you with a sense of the broad theoretical perspectives in social work that might be relevant to your project.

- Try to find small-t theories that are more specific to your topic area and relevant to your working question.

Exercises

- In Chapter 2, you developed a concept map for your proposal. Take a moment to revisit your concept map now as your theoretical framework is taking shape. Make any updates to the key concepts and relationships in your concept map.

. If you need a refresher, we have embedded a short how-to video from the University of Guelph Library (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0) that we also used in Chapter 2.

8.2 Conceptual definitions

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define conceptualization

- Identify the role previous research and theory play in defining concepts

- Distinguish between unidimensional and multidimensional concepts

- Critically apply reification to how you conceptualize the key variables in your research project

In order to measure the concepts in your research question, we first have to understand what we think about them. As an aside, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it is important to be sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity. While there are many possible ways to define the term and some may be more common or have more support than others, there is no universal definition of masculinity. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.\

Not all researchers clearly explain their theoretical or conceptual framework for their study, but they should! Without understanding how a researcher has defined their key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Back in Chapter 7, you developed a theoretical framework for your study based on a survey of the theoretical literature in your topic area. If you haven’t done that yet, consider flipping back to that section to familiarize yourself with some of the techniques for finding and using theories relevant to your research question. Continuing with our example on masculinity, we would need to survey the literature on theories of masculinity. After a few queries on masculinity, I found a wonderful article by Wong (2010)[14] that analyzed eight years of the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinity and analyzed how often different theories of masculinity were used. Not only can I get a sense of which theories are more accepted and which are more marginal in the social science on masculinity, I am able to identify a range of options from which I can find the theory or theories that will inform my project.

Exercises

Identify a specific theory (or more than one theory) and how it helps you understand…

- Your independent variable(s).

- Your dependent variable(s).

- The relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Rather than completing this exercise from scratch, build from your theoretical or conceptual framework developed in previous chapters.

Conceptualization

In quantitative methods, conceptualization involves writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts. These are the kind of definitions you are used to, like the ones in a dictionary. A conceptual definition involves defining a concept in terms of other concepts, usually by making reference to how other social scientists and theorists have defined those concepts in the past. Of course, new conceptual definitions are created all the time because our conceptual understanding of the world is always evolving.

Conceptualization is deceptively challenging—spelling out exactly what the concepts in your research question mean to you. Following along with our example, think about what comes to mind when you read the term masculinity. How do you know masculinity when you see it? Does it have something to do with men or with social norms? If so, perhaps we could define masculinity as the social norms that men are expected to follow. That seems like a reasonable start, and at this early stage of conceptualization, brainstorming about the images conjured up by concepts and playing around with possible definitions is appropriate. However, this is just the first step. At this point, you should be beyond brainstorming for your key variables because you have read a good amount of research about them

In addition, we should consult previous research and theory to understand the definitions that other scholars have already given for the concepts we are interested in. This doesn’t mean we must use their definitions, but understanding how concepts have been defined in the past will help us to compare our conceptualizations with how other scholars define and relate concepts. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work. Finally, working on conceptualization is likely to help in the process of refining your research question to one that is specific and clear in what it asks. Conceptualization and operationalization (next section) are where “the rubber meets the road,” so to speak, and you have to specify what you mean by the question you are asking. As your conceptualization deepens, you will often find that your research question becomes more specific and clear.

Evaluate scholars’ definitions

If we turn to the literature on masculinity, we will surely come across work by Michael Kimmel, one of the preeminent masculinity scholars in the United States. After consulting Kimmel’s prior work (2000; 2008),[15] we might tweak our initial definition of masculinity. Rather than defining masculinity as “the social norms that men are expected to follow,” perhaps instead we’ll define it as “the social roles, behaviors, and meanings prescribed for men in any given society at any one time” (Kimmel & Aronson, 2004, p. 503).[16] Our revised definition is more precise and complex because it goes beyond addressing one aspect of men’s lives (norms), and addresses three aspects: roles, behaviors, and meanings. It also implies that roles, behaviors, and meanings may vary across societies and over time. Using definitions developed by theorists and scholars is a good idea, though you may find that you want to define things your own way.

Situate the definition in theory

As you can see, conceptualization isn’t as simple as applying any random definition that we come up with to a term. Defining our terms may involve some brainstorming at the very beginning. But conceptualization must go beyond that, to engage with or critique existing definitions and conceptualizations in the literature. Once we’ve brainstormed about the images associated with a particular word, we should also consult prior work to understand how others define the term in question. After we’ve identified a clear definition that we’re happy with, we should make sure that every term used in our definition will make sense to others. Are there terms used within our definition that also need to be defined? If so, our conceptualization is not yet complete. Our definition includes the concept of “social roles,” so we should have a definition for what those mean and become familiar with role theory to help us with our conceptualization. If we don’t know what roles are, how can we study them?

Multiple dimensions

Let’s say we do all of that. We have a clear definition of the term masculinity with reference to previous literature and we also have a good understanding of the terms in our conceptual definition…then we’re done, right? Not so fast. You’ve likely met more than one man in your life, and you’ve probably noticed that they are not the same, even if they live in the same society during the same historical time period. This could mean there are dimensions of masculinity. In terms of social scientific measurement, concepts can be said to have multiple dimensions when there are multiple elements that make up a single concept. With respect to the term masculinity, dimensions could based on gender identity, gender performance, sexual orientation, etc.. In any of these cases, the concept of masculinity would be considered to have multiple dimensions.

While you do not need to spell out every possible dimension of the concepts you wish to measure, it is important to identify whether your concepts are unidimensional (and therefore relatively easy to define and measure) or multidimensional (and therefore require multi-part definitions and measures). In this way, how you conceptualize your variables determines how you will measure them in your study. Unidimensional concepts are those that are expected to have a single underlying dimension. These concepts can be measured using a single measure or test. Examples include simple concepts such as a person’s weight, time spent sleeping, and so forth.

One frustrating this is that there is no clear demarcation between concepts that are inherently unidimensional or multidimensional. Even something as simple as age could be broken down into multiple dimensions including mental age and chronological age, so where does conceptualization stop? How far down the dimensional rabbit hole do we have to go? Researchers should consider two things. First, how important is this variable in your study? If age is not important in your study (maybe it is a control variable), it seems like a waste of time to do a lot of work drawing from developmental theory to conceptualize this variable. A unidimensional measure from zero to dead is all the detail we need. On the other hand, if we were measuring the impact of age on masculinity, conceptualizing our independent variable (age) as multidimensional may provide a richer understanding of its impact on masculinity. Finally, your conceptualization will lead directly to your operationalization of the variable, and once your operationalization is complete, make sure someone reading your study could follow how your conceptual definitions informed the measures you chose for your variables.

Exercises

Write a conceptual definition for your independent and dependent variables.

- Cite and attribute definitions to other scholars, if you use their words.

- Describe how your definitions are informed by your theoretical framework.

- Place your definition in conversation with other theories and conceptual definitions commonly used in the literature.

- Are there multiple dimensions of your variables?

- Are any of these dimensions important for you to measure?

Do researchers actually know what we’re talking about?

Conceptualization proceeds differently in qualitative research compared to quantitative research. Since qualitative researchers are interested in the understandings and experiences of their participants, it is less important for them to find one fixed definition for a concept before starting to interview or interact with participants. The researcher’s job is to accurately and completely represent how their participants understand a concept, not to test their own definition of that concept.

If you were conducting qualitative research on masculinity, you would likely consult previous literature like Kimmel’s work mentioned above. From your literature review, you may come up with a working definition for the terms you plan to use in your study, which can change over the course of the investigation. However, the definition that matters is the definition that your participants share during data collection. A working definition is merely a place to start, and researchers should take care not to think it is the only or best definition out there.

In qualitative inquiry, your participants are the experts (sound familiar, social workers?) on the concepts that arise during the research study. Your job as the researcher is to accurately and reliably collect and interpret their understanding of the concepts they describe while answering your questions. Conceptualization of concepts is likely to change over the course of qualitative inquiry, as you learn more information from your participants. Indeed, getting participants to comment on, extend, or challenge the definitions and understandings of other participants is a hallmark of qualitative research. This is the opposite of quantitative research, in which definitions must be completely set in stone before the inquiry can begin.

The contrast between qualitative and quantitative conceptualization is instructive for understanding how quantitative methods (and positivist research in general) privilege the knowledge of the researcher over the knowledge of study participants and community members. Positivism holds that the researcher is the “expert,” and can define concepts based on their expert knowledge of the scientific literature. This knowledge is in contrast to the lived experience that participants possess from experiencing the topic under examination day-in, day-out. For this reason, it would be wise to remind ourselves not to take our definitions too seriously and be critical about the limitations of our knowledge.

Conceptualization must be open to revisions, even radical revisions, as scientific knowledge progresses. While I’ve suggested consulting prior scholarly definitions of our concepts, you should not assume that prior, scholarly definitions are more real than the definitions we create. Likewise, we should not think that our own made-up definitions are any more real than any other definition. It would also be wrong to assume that just because definitions exist for some concept that the concept itself exists beyond some abstract idea in our heads. Building on the paradigmatic ideas behind interpretivism and the critical paradigm, researchers call the assumption that our abstract concepts exist in some concrete, tangible way is known as reification. It explores the power dynamics behind how we can create reality by how we define it.

Returning again to our example of masculinity. Think about our how our notions of masculinity have developed over the past few decades, and how different and yet so similar they are to patriarchal definitions throughout history. Conceptual definitions become more or less popular based on the power arrangements inside of social science the broader world. Western knowledge systems are privileged, while others are viewed as unscientific and marginal. The historical domination of social science by white men from WEIRD countries meant that definitions of masculinity were imbued their cultural biases and were designed explicitly and implicitly to preserve their power. This has inspired movements for cognitive justice as we seek to use social science to achieve global development.

Key Takeaways

- Measurement is the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating.

- Kaplan identified three categories of things that social scientists measure including observational terms, indirect observables, and constructs.

- Some concepts have multiple elements or dimensions.

- Researchers often use measures previously developed and studied by other researchers.

- Conceptualization is a process that involves coming up with clear, concise definitions.

- Conceptual definitions are based on the theoretical framework you are using for your study (and the paradigmatic assumptions underlying those theories).

- Whether your conceptual definitions come from your own ideas or the literature, you should be able to situate them in terms of other commonly used conceptual definitions.

- Researchers should acknowledge the limited explanatory power of their definitions for concepts and how oppression can shape what explanations are considered true or scientific.

Exercises

Think historically about the variables in your research question.

- How has our conceptual definition of your topic changed over time?

- What scholars or social forces were responsible for this change?

Take a critical look at your conceptual definitions.

- How participants might define terms for themselves differently, in terms of their daily experience?

- On what cultural assumptions are your conceptual definitions based?

- Are your conceptual definitions applicable across all cultures that will be represented in your sample?

8.3 Inductive and deductive reasoning

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe inductive and deductive reasoning and provide examples of each

- Identify how inductive and deductive reasoning are complementary

While your theoretical framework is likely to develop as your project unfolds, you should have a good sense of what theory or theories will be relevant to your project. If you don’t have a good idea about those at this point, it may be a good opportunity to pause and read more about the theories related to your topic area. You need a place to start theoretically, even if you end up in a different place by the end of your project.

Theories structure and inform social work research. The converse is also true: research can structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach. While inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

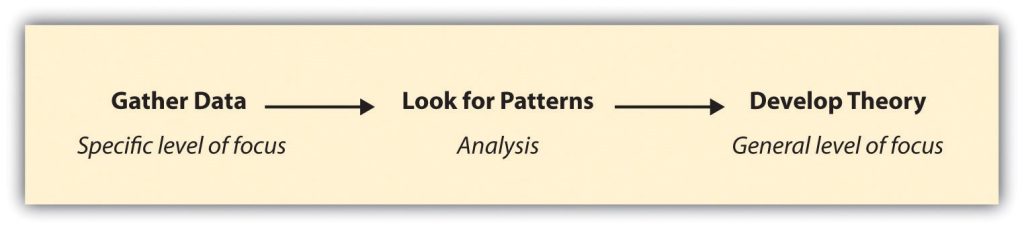

Inductive reasoning

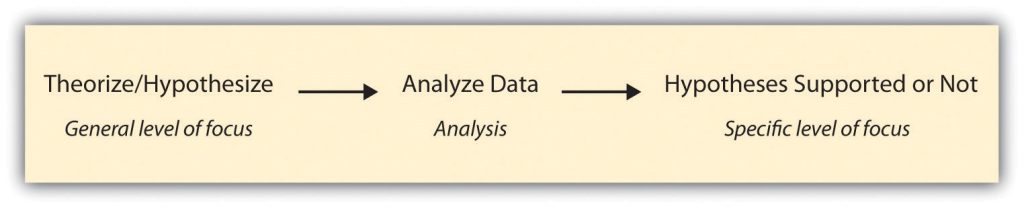

A researcher using inductive reasoning begins by collecting data that is relevant to their topic of interest. Once a substantial amount of data have been collected, the researcher will then step back from data collection to get a bird’s eye view of their data. At this stage, the researcher looks for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a particular set of observations and move to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 8.1 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating study in which the researchers took an inductive approach is Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s (2011)[17] study of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young cisgender men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 cisgender men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation, that menstruation makes boys feel somewhat separated from girls, and that as they enter young adulthood and form romantic relationships, young men develop more mature attitudes about menstruation. Note how this study began with the data—men’s narratives of learning about menstruation—and worked to develop a theory.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)[18] analyzed empirical data to better understand how to meet the needs of young people who are homeless. The authors analyzed focus group data from 20 youth at a homeless shelter. From these data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve homeless youth. The researchers also developed hypotheses for others who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test their hypotheses, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a theory and a hypothesis derived from that theory. Section 8.4 discusses the use of mixed methods research as a way for researchers to test hypotheses created in a previous component of the same research project.

You will notice from both of these examples that inductive reasoning is most commonly found in studies using qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews. Because inductive reasoning involves the creation of a new theory, researchers need very nuanced data on how the key concepts in their working question operate in the real world. Qualitative data is often drawn from lengthy interactions and observations with the individuals and phenomena under examination. For this reason, inductive reasoning is most often associated with qualitative methods, though it is used in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Deductive reasoning

If inductive reasoning is about creating theories from raw data, deductive reasoning is about testing theories using data. Researchers using deductive reasoning take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a compelling social theory, create a hypothesis about how the world should work, collect raw data, and analyze whether their hypothesis was confirmed or not. That is, deductive approaches move from a more general level (theory) to a more specific (data); whereas inductive approaches move from the specific (data) to general (theory).

A deductive approach to research is the one that people typically associate with scientific investigation. Students in English-dominant countries that may be confused by inductive vs. deductive research can rest part of the blame on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes character. As Craig Vasey points out in his breezy introduction to logic book chapter, Sherlock Holmes more often used inductive rather than deductive reasoning (despite claiming to use the powers of deduction to solve crimes). By noticing subtle details in how people act, behave, and dress, Holmes finds patterns that others miss. Using those patterns, he creates a theory of how the crime occurred, dramatically revealed to the authorities just in time to arrest the suspect. Indeed, it is these flashes of insight into the patterns of data that make Holmes such a keen inductive reasoner. In social work practice, rather than detective work, inductive reasoning is supported by the intuitions and practice wisdom of social workers, just as Holmes’ reasoning is sharpened by his experience as a detective.

So, if deductive reasoning isn’t Sherlock Holmes’ observation and pattern-finding, how does it work? It starts with what you have already done in Chapters 3 and 4, reading and evaluating what others have done to study your topic. It continued with Chapter 5, discovering what theories already try to explain how the concepts in your working question operate in the real world. Tapping into this foundation of knowledge on their topic, the researcher studies what others have done, reads existing theories of whatever phenomenon they are studying, and then tests hypotheses that emerge from those theories. Figure 8.2 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, many do. We’ll now take a look at a couple excellent examples of deductive research.

In a study of US law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)[19] hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from prior research and theories on the topic. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis and illustrated an important application of critical race theory.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)[20] studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. One might associate this research with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or systems theory. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).[21]

Complementary approaches

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their study to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

Dr. Amy Blackstone (n.d.), author of Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods, relates a story about her mixed methods research on sexual harassment.

We began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004)[22], we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),[23] we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work. (Blackstone, n.d., p. 21)[24]

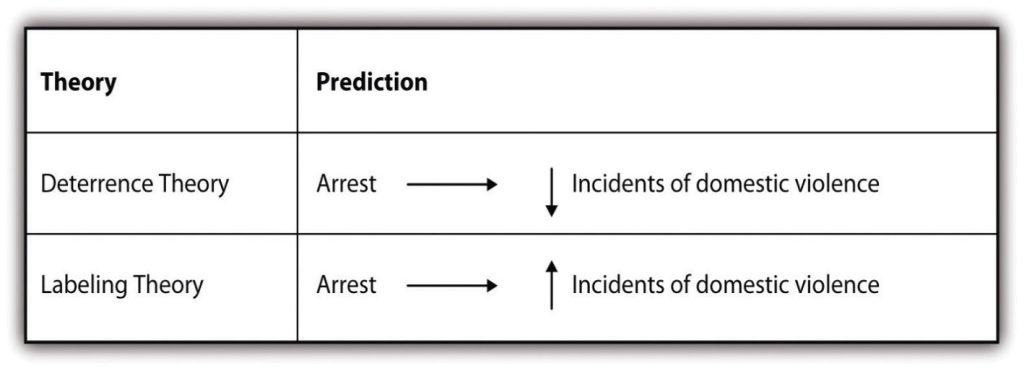

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).[25] As Schutt describes, researchers Sherman and Berk (1984)[26] conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence).Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory (see Williams, 2005[27] for more information on that theory) would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused batterers than labeling theory. Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused spouse batterer will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting accused spouse batterers will increase future incidents (see Policastro & Payne, 2013[28] for more information on that theory). Figure 8.3 summarizes the two competing theories and the hypotheses Sherman and Berk set out to test.

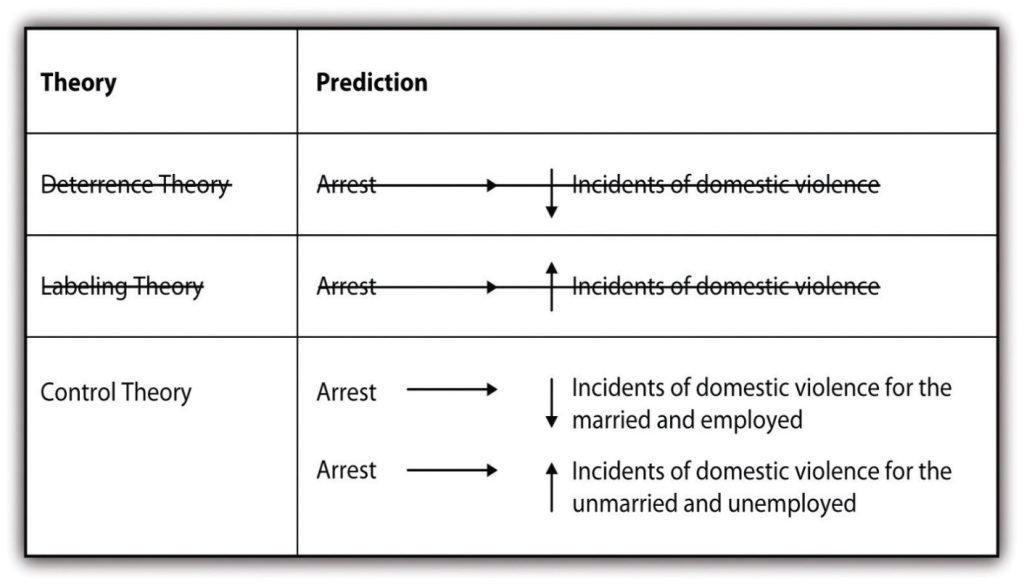

Research from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed, but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which posits that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation (see Davis et al., 2000[30] for more information on this theory).

What the original Sherman and Berk study, along with the follow-up studies, show us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. We will expand on these possibilities in section 8.4 when we discuss mixed methods research.

Recall our framework for research in chapter 1. On the right side, deductive research derives hypotheses from prior empirical results or social theory and tests them using research methods. Inductive researchers evaluate those findings, and in combining a large number of data points across a wide body of studies, revise and construct new theories about the social world.

Ethical and critical considerations

Deductive and inductive reasoning, just like other components of the research process comes with ethical and cultural considerations for researchers. Specifically, deductive research is limited by existing theory. Because scientific inquiry has been shaped by oppressive forces such as sexism, racism, and colonialism, what is considered theory is largely based in Western, white-male-dominant culture. Thus, researchers doing deductive research may artificially limit themselves to ideas that were derived from this context. Non-Western researchers, international social workers, and practitioners working with non-dominant groups may find deductive reasoning of limited help if theories do not adequately describe other cultures.

While these flaws in deductive research may make inductive reasoning seem more appealing, on closer inspection you’ll find similar issues apply. A researcher using inductive reasoning applies their intuition and lived experience when analyzing participant data. They will take note of particular themes, conceptualize their definition, and frame the project using their unique psychology. Since everyone’s internal world is shaped by their cultural and environmental context, inductive reasoning conducted by Western researchers may unintentionally reinforcing lines of inquiry that derive from cultural oppression.

Inductive reasoning is also shaped by those invited to provide the data to be analyzed. For example, I recently worked with a student who wanted to understand the impact of child welfare supervision on children born dependent on opiates and methamphetamine. Due to the potential harm that could come from interviewing families and children who are in foster care or under child welfare supervision, the researcher decided to use inductive reasoning and to only interview child welfare workers.

Talking to practitioners is a good idea for feasibility, as they are less vulnerable than clients. However, any theory that emerges out of these observations will be substantially limited, as it would be devoid of the perspectives of parents, children, and other community members who could provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of child welfare involvement on children. Notice that each of these groups has less power than child welfare workers in the service relationship. Attending to which groups were used to inform the creation of a theory and the power of those groups is an important critical consideration for social work researchers.

As you can see, when researchers apply theory to research they must wrestle with the history and hierarchy around knowledge creation in that area. In deductive studies, the researcher is positioned as the expert, similar to the positivist paradigm presented in Chapter 5. We’ve discussed a few of the limitations on the knowledge of researchers in this subsection, but the position of the “researcher as expert” is inherently problematic. However, it should also not be taken to an extreme. A researcher who approaches inductive inquiry as a naïve learner is also inherently problematic. Just as competence in social work practice requires a baseline of knowledge prior to entering practice, so does competence in social work research. Because a truly naïve intellectual position is impossible—we all have preexisting ways we view the world and are not fully aware of how they may impact our thoughts—researchers should be well-read in the topic area of their research study but humble enough to know that there is always much more to learn.

Key Takeaways

- Inductive reasoning begins with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- Deductive reasoning begins with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test the truth of those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive reasoning can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the research topic.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive reasoning in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

Exercises

- Identify one theory and how it helps you understand your topic and working question.

I encourage you to find a specific theory from your topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay…but I promise that searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Using the theory you identified, describe what you expect the answer to be to your working question.

8.4 Nomothetic causal relationships

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define and provide an example of idiographic causal relationships

- Describe the role of causality in quantitative research as compared to qualitative research

- Identify, define, and describe each of the main criteria for nomothetic causal relationships

- Describe the difference between and provide examples of independent, dependent, and control variables

- Define hypothesis, state a clear hypothesis, and discuss the respective roles of quantitative and qualitative research when it comes to hypotheses

Causality refers to the idea that one event, behavior, or belief will result in the occurrence of another, subsequent event, behavior, or belief. In other words, it is about cause and effect. It seems simple, but you may be surprised to learn there is more than one way to explain how one thing causes another. How can that be? How could there be many ways to understand causality?

Think back to our discussion in Section 5.3 on paradigms [insert chapter link plus link to section 1.2]. You’ll remember the positivist paradigm as the one that believes in objectivity. Positivists look for causal explanations that are universally true for everyone, everywhere because they seek objective truth. Interpretivists, on the other hand, look for causal explanations that are true for individuals or groups in a specific time and place because they seek subjective truths. Remember that for interpretivists, there is not one singular truth that is true for everyone, but many truths created and shared by others.

“Are you trying to generalize or nah?”

One of my favorite classroom moments occurred in the early days of my teaching career. Students were providing peer feedback on their working questions. I overheard one group who was helping someone rephrase their research question. A student asked, “Are you trying to generalize or nah?” Teaching is full of fun moments like that one. Answering that one question can help you understand how to conceptualize and design your research project.

Nomothetic causal explanations are incredibly powerful. They allow scientists to make predictions about what will happen in the future, with a certain margin of error. Moreover, they allow scientists to generalize—that is, make claims about a large population based on a smaller sample of people or items. Generalizing is important. We clearly do not have time to ask everyone their opinion on a topic or test a new intervention on every person. We need a type of causal explanation that helps us predict and estimate truth in all situations.

Generally, nomothetic causal relationships work best for explanatory research projects [INSERT SECTION LINK]. They also tend to use quantitative research: by boiling things down to numbers, one can use the universal language of mathematics to use statistics to explore those relationships. On the other hand, descriptive and exploratory projects often fit better with idiographic causality. These projects do not usually try to generalize, but instead investigate what is true for individuals, small groups, or communities at a specific point in time. You will learn about this type of causality in the next section. Here, we will assume you have an explanatory working question. For example, you may want to know about the risk and protective factors for a specific diagnosis or how a specific therapy impacts client outcomes.

What do nomothetic causal explanations look like?

Nomothetic causal explanations express relationships between variables. The term variable has a scientific definition. This one from Gillespie & Wagner (2018) “a logical grouping of attributes that can be observed and measured and is expected to vary from person to person in a population” (p. 9).[31] More practically, variables are the key concepts in your working question. You know, the things you plan to observe when you actually do your research project, conduct your surveys, complete your interviews, etc. These things have two key properties. First, they vary, as in they do not remain constant. “Age” varies by number. “Gender” varies by category. But they both vary. Second, they have attributes. So the variable “health professions” has attributes or categories, such as social worker, nurse, counselor, etc.

It’s also worth reviewing what is not a variable. Well, things that don’t change (or vary) aren’t variables. If you planned to do a study on how gender impacts earnings but your study only contained women, that concept would not vary. Instead, it would be a constant. Another common mistake I see in students’ explanatory questions is mistaking an attribute for a variable. “Men” is not a variable. “Gender” is a variable. “Virginia” is not a variable. The variable is the “state or territory” in which someone or something is physically located.

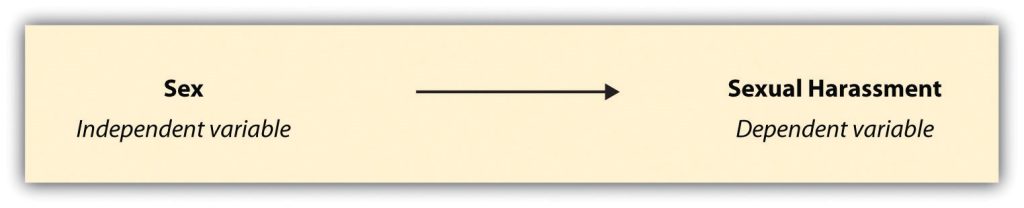

When one variable causes another, we have what researchers call independent and dependent variables. For example, in a study investigating the impact of spanking on aggressive behavior, spanking would be the independent variable and aggressive behavior would be the dependent variable. An independent variable is the cause, and a dependent variable is the effect. Why are they called that? Dependent variables depend on independent variables. If all of that gets confusing, just remember the graphical relationship in Figure 8.5.

Exercises

Write out your working question, as it exists now. As we said previously in the subsection, we assume you have an explanatory research question for learning this section.

- Write out a diagram similar to Figure 8.5.

- Put your independent variable on the left and the dependent variable on the right.

Check:

- Can your variables vary?

- Do they have different attributes or categories that vary from person to person?

- How does the theory you identified in section 6.1 help you understand this causal relationship?

If the theory you’ve identified isn’t much help to you or seems unrelated, it’s a good indication that you need to read more literature about the theories related to your topic.

For some students, your working question may not be specific enough to list an independent or dependent variable clearly. You may have “risk factors” in place of an independent variable, for example. Or “effects” as a dependent variable. If that applies to your research question, get specific for a minute even if you have to revise this later. Think about which specific risk factors or effects you are interested in. Consider a few options for your independent and dependent variable and create diagrams similar to Figure 8.5.

Finally, you are likely to revisit your working question so you may have to come back to this exercise to clarify the causal relationship you want to investigate.

For a ten-cent word like “nomothetic,” these causal relationships should look pretty basic to you. They should look like “x causes y.” Indeed, you may be looking at your causal explanation and thinking, “wow, there are so many other things I’m missing in here.” In fact, maybe my dependent variable sometimes causes changes in my independent variable! For example, a working question asking about poverty and education might ask how poverty makes it more difficult to graduate college or how high college debt impacts income inequality after graduation. Nomothetic causal relationships are slices of reality. They boil things down to two (or often more) key variables and assert a one-way causal explanation between them. This is by design, as they are trying to generalize across all people to all situations. The more complicated, circular, and often contradictory causal explanations are idiographic, which we will cover in the next section of this chapter.

Developing a hypothesis

A hypothesis is a statement describing a researcher’s expectation regarding what they anticipate finding. Hypotheses in quantitative research are a nomothetic causal relationship that the researcher expects to determine is true or false. A hypothesis is written to describe the expected relationship between the independent and dependent variables. In other words, write the answer to your working question using your variables. That’s your hypothesis! Make sure you haven’t introduced new variables into your hypothesis that are not in your research question. If you have, write out your hypothesis as in Figure 8.5.

A good hypothesis should be testable using social science research methods. That is, you can use a social science research project (like a survey or experiment) to test whether it is true or not. A good hypothesis is also specific about the relationship it explores. For example, a student project that hypothesizes, “families involved with child welfare agencies will benefit from Early Intervention programs,” is not specific about what benefits it plans to investigate. For this student, I advised her to take a look at the empirical literature and theory about Early Intervention and see what outcomes are associated with these programs. This way, she could more clearly state the dependent variable in her hypothesis, perhaps looking at reunification, attachment, or developmental milestone achievement in children and families under child welfare supervision.

Your hypothesis should be an informed prediction based on a theory or model of the social world. For example, you may hypothesize that treating mental health clients with warmth and positive regard is likely to help them achieve their therapeutic goals. That hypothesis would be based on the humanistic practice models of Carl Rogers. Using previous theories to generate hypotheses is an example of deductive research. If Rogers’ theory of unconditional positive regard is accurate, a study comparing clinicians who used it versus those who did not would show more favorable treatment outcomes for clients receiving unconditional positive regard.

Let’s consider a couple of examples. In research on sexual harassment (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004),[32] one might hypothesize, based on feminist theories of sexual harassment, that more females than males will experience specific sexually harassing behaviors. What is the causal relationship being predicted here? Which is the independent and which is the dependent variable? In this case, researchers hypothesized that a person’s sex (independent variable) would predict their likelihood to experience sexual harassment (dependent variable).

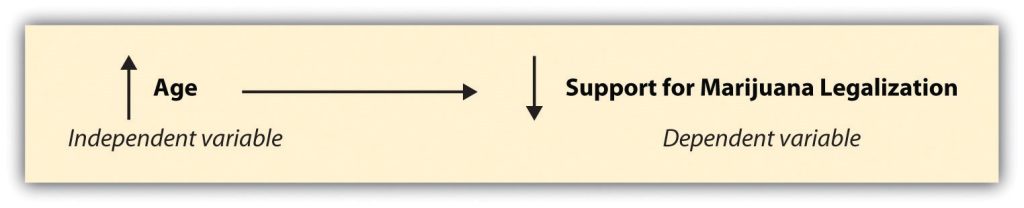

Sometimes researchers will hypothesize that a relationship will take a specific direction. As a result, an increase or decrease in one area might be said to cause an increase or decrease in another. For example, you might choose to study the relationship between age and support for legalization of marijuana. Perhaps you’ve taken a sociology class and, based on the theories you’ve read, you hypothesize that age is negatively related to support for marijuana legalization.[33] What have you just hypothesized?

You have hypothesized that as people get older, the likelihood of their supporting marijuana legalization decreases. Thus, as age (your independent variable) moves in one direction (up), support for marijuana legalization (your dependent variable) moves in another direction (down). So, a direct relationship (or positive correlation) involve two variables going in the same direction and an inverse relationship (or negative correlation) involve two variables going in opposite directions. If writing hypotheses feels tricky, it is sometimes helpful to draw them out and depict each of the two hypotheses we have just discussed.

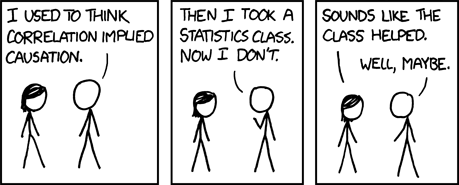

It’s important to note that once a study starts, it is unethical to change your hypothesis to match the data you find. For example, what happens if you conduct a study to test the hypothesis from Figure 8.7 on support for marijuana legalization, but you find no relationship between age and support for legalization? It means that your hypothesis was incorrect, but that’s still valuable information. It would challenge what the existing literature says on your topic, demonstrating that more research needs to be done to figure out the factors that impact support for marijuana legalization. Don’t be embarrassed by negative results, and definitely don’t change your hypothesis to make it appear correct all along!

Criteria for establishing a nomothetic causal relationship

Let’s say you conduct your study and you find evidence that supports your hypothesis, as age increases, support for marijuana legalization decreases. Success! Causal explanation complete, right? Not quite.

You’ve only established one of the criteria for causality. The criteria for causality must include all of the following: covariation, plausibility, temporality, and nonspuriousness. In our example from Figure 8.7, we have established only one criteria—covariation. When variables covary, they vary together. Both age and support for marijuana legalization vary in our study. Our sample contains people of varying ages and varying levels of support for marijuana legalization. If, for example, we only included 16-year-olds in our study, age would be a constant, not a variable.

Just because there might be some correlation between two variables does not mean that a causal relationship between the two is really plausible. Plausibility means that in order to make the claim that one event, behavior, or belief causes another, the claim has to make sense. It makes sense that people from previous generations would have different attitudes towards marijuana than younger generations. People who grew up in the time of Reefer Madness or the hippies may hold different views than those raised in an era of legalized medicinal and recreational use of marijuana. Plausibility is of course helped by basing your causal explanation in existing theoretical and empirical findings.

Once we’ve established that there is a plausible relationship between the two variables, we also need to establish whether the cause occurred before the effect, the criterion of temporality. A person’s age is a quality that appears long before any opinions on drug policy, so temporally the cause comes before the effect. It wouldn’t make any sense to say that support for marijuana legalization makes a person’s age increase. Even if you could predict someone’s age based on their support for marijuana legalization, you couldn’t say someone’s age was caused by their support for legalization of marijuana.

Finally, scientists must establish nonspuriousness. A spurious relationship is one in which an association between two variables appears to be causal but can in fact be explained by some third variable. This third variable is often called a confound or confounding variable because it clouds and confuses the relationship between your independent and dependent variable, making it difficult to discern the true causal relationship is.

Continuing with our example, we could point to the fact that older adults are less likely to have used marijuana recreationally. Maybe it is actually recreational use of marijuana that leads people to be more open to legalization, not their age. In this case, our confounding variable would be recreational marijuana use. Perhaps the relationship between age and attitudes towards legalization is a spurious relationship that is accounted for by previous use. This is also referred to as the third variable problem, where a seemingly true causal relationship is actually caused by a third variable not in the hypothesis. In this example, the relationship between age and support for legalization could be more about having tried marijuana than the age of the person.

Quantitative researchers are sensitive to the effects of potentially spurious relationships. As a result, they will often measure these third variables in their study, so they can control for their effects in their statistical analysis. These are called control variables, and they refer to potentially confounding variables whose effects are controlled for mathematically in the data analysis process. Control variables can be a bit confusing, and we will discuss them more in Chapter 10, but think about it as an argument between you, the researcher, and a critic.

Researcher: “The older a person is, the less likely they are to support marijuana legalization.”

Critic: “Actually, it’s more about whether a person has used marijuana before. That is what truly determines whether someone supports marijuana legalization.”

Researcher: “Well, I measured previous marijuana use in my study and mathematically controlled for its effects in my analysis. Age explains most of the variation in attitudes towards marijuana legalization.”

Let’s consider a few additional, real-world examples of spuriousness. Did you know, for example, that high rates of ice cream sales have been shown to cause drowning? Of course, that’s not really true, but there is a positive relationship between the two. In this case, the third variable that causes both high ice cream sales and increased deaths by drowning is time of year, as the summer season sees increases in both (Babbie, 2010).[34]

Here’s another good one: it is true that as the salaries of Presbyterian ministers in Massachusetts rise, so too does the price of rum in Havana, Cuba. Well, duh, you might be saying to yourself. Everyone knows how much ministers in Massachusetts love their rum, right? Not so fast. Both salaries and rum prices have increased, true, but so has the price of just about everything else (Huff & Geis, 1993).[35]

Finally, research shows that the more firefighters present at a fire, the more damage is done at the scene. What this statement leaves out, of course, is that as the size of a fire increases so too does the amount of damage caused as does the number of firefighters called on to help (Frankfort-Nachmias & Leon-Guerrero, 2011).[36] In each of these examples, it is the presence of a confounding variable that explains the apparent relationship between the two original variables.

In sum, the following criteria must be met for a nomothetic causal relationship:

- The two variables must vary together.

- The relationship must be plausible.

- The cause must precede the effect in time.

- The relationship must be nonspurious (not due to a confounding variable).

The hypothetico-dedutive method

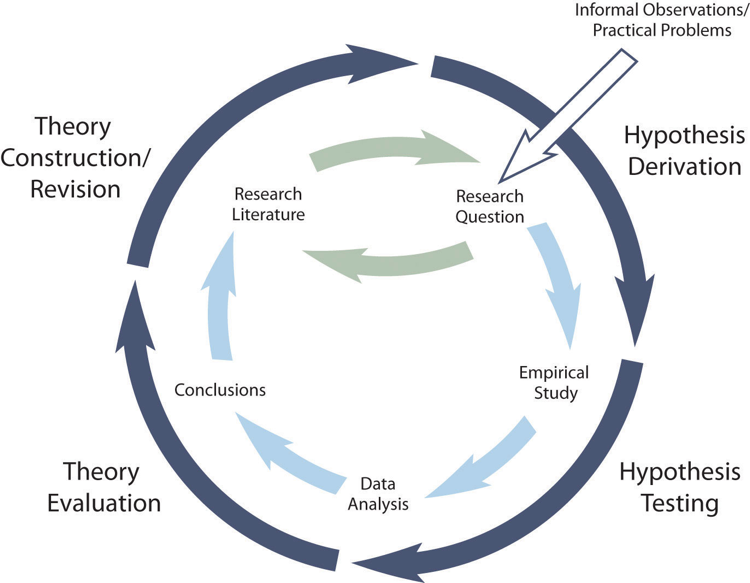

The primary way that researchers in the positivist paradigm use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers choose an existing theory. Then, they make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they reevaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary.

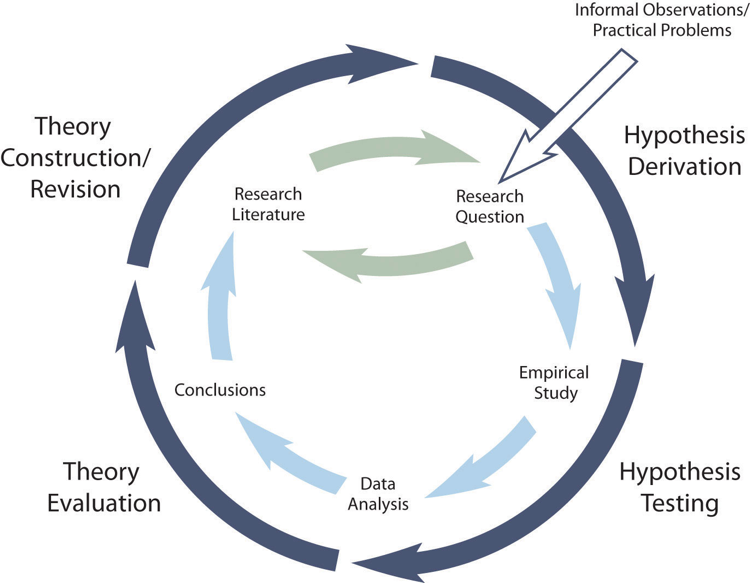

This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 8.8 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the process of conducting a research project—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research. Together, they form a model of theoretically motivated research.

Keep in mind the hypothetico-deductive method is only one way of using social theory to inform social science research. It starts with describing one or more existing theories, deriving a hypothesis from one of those theories, testing your hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluating the theory based on the results data analyses. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

But what if your research question is more interpretive? What if it is less about theory-testing and more about theory-building? This is what our next chapters will cover: the process of inductively deriving theory from people’s stories and experiences. This process looks different than that depicted in Figure 8.8. It still starts with your research question and answering that question by conducting a research study. But instead of testing a hypothesis you created based on a theory, you will create a theory of your own that explain the data you collected. This format works well for qualitative research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address.

Key Takeaways

- In positivist and quantitative studies, the goal is often to understand the more general causes of some phenomenon rather than the idiosyncrasies of one particular instance, as in an idiographic causal relationship.

- Nomothetic causal explanations focus on objectivity, prediction, and generalization.

- Criteria for nomothetic causal relationships require the relationship be plausible and nonspurious; and that the cause must precede the effect in time.

- In a nomothetic causal relationship, the independent variable causes changes in the dependent variable.

- Hypotheses are statements, drawn from theory, which describe a researcher’s expectation about a relationship between two or more variables.

Exercises

- Write out your working question and hypothesis.

- Defend your hypothesis in a short paragraph, using arguments based on the theory you identified in section 8.1.

- Review the criteria for a nomothetic causal relationship. Critique your short paragraph about your hypothesis using these criteria.

- Are there potentially confounding variables, issues with time order, or other problems you can identify in your reasoning?

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of research in personality, 19(2), 109-134. ↵

- Abery, B., & Stancliffe, R. (1996). The ecology of self-determination. in Self-determination across the life span: Independence and choice for people with disabilities (pp. 111-145.) Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company ↵

- Payne, M. (2014). Modern social work theory. Oxford University Press. ↵

- Hutchison, E. D. (2014). Dimensions of human behavior: Person and environment. Sage Publications. ↵

- DeCoster, S., Estes, S. B., & Mueller, C. W. (1999). Routine activities and sexual harassment in the workplace. Work and Occupations, 26, 21–49. ↵

- Morgan, P. A. (1999). Risking relationships: Understanding the litigation choices of sexually harassed women. The Law and Society Review, 33, 201–226. ↵

- MacKinnon, C. (1979). Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ↵

- An, S., Yoo, J., & Nackerud, L. G. (2015). Using game theory to understand screening for domestic violence under the TANF family violence option. Advances in Social Work, 16(2), 338-357. ↵

- Pellebon, D. A. (2007). An analysis of Afrocentricity as theory for social work practice. Advances in Social Work, 8(1), 169-183. ↵