21

Matthew DeCarlo

2.3 Practical and ethical considerations for collecting data

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify potential stakeholders and gatekeepers

- Differentiate between raw data and the results of scientific studies

- Evaluate whether you can feasibly complete your project

Are you interested in better understanding the day-to-day experiences of maximum security prisoners? This sounds fascinating, but unless you plan to commit a crime that lands you in a maximum security prison, gaining access to that particular population would be difficult for a graduate student project. While the topics about which social work questions can be asked may seem limitless, there are limits to which aspects of topics we can study or at least to the ways we can study them. This is particularly true for research projects completed by students.

Feasibility refers to whether you can practically conduct the study you plan to do, given the resources and ethical obligations you have. In this section, we assume that you will have to actually conduct the research project that you write about in your research proposal. It’s a good time to check with your professor about your program’s expectations for student research projects. For students who do not have to carry out their projects, feasibility is less of a concern because, well, you don’t actually have to carry out your project. Instead, you’ll propose a project that could work in theory. However, for students who have to carry out the projects in their research proposals, feasibility is incredibly important. In this section, we will review the important practical and ethical considerations student researchers should start thinking about from the beginning of a research project.

Access, consent, and ethical obligations

One of the most important feasibility issues is gaining access to your target population. For example, let’s say you wanted to better understand middle-school students who engaged in self-harm behaviors. That is a topic of social importance, so why might it make for a difficult student project? Let’s say you proposed to identify students from a local middle school and interview them about self-harm. Methodologically, that sounds great since you are getting data from those with the most knowledge about the topic, the students themselves. But practically, that sounds challenging. Think about the ethical obligations a social work practitioner has to adolescents who are engaging in self-harm (e.g., competence, respect). In research, we are similarly concerned mostly with the benefits and harms of what you propose to do as well as the openness and honesty with which you share your project publicly.

Gatekeepers

If you were the principal at your local middle school, would you allow an MSW student to interview kids in your schools about self-harm? What if the results of the study showed that self-harm was a big problem that your school was not addressing? What if the researcher’s interviews themselves caused an increase in self-harming behaviors among the children? The principal in this situation is a gatekeeper. Gatekeepers are the individuals or organizations who control access to the population you want to study. The school board would also likely need to give consent for the research to take place at their institution. Gatekeepers must weigh their ethical questions because they have a responsibility to protect the safety of the people at their organization, just as you have an ethical obligation to protect the people in your research study.

For student projects, it can be a challenge to get consent from gatekeepers to conduct your research project. As a result, students often conduct research projects at their place of employment or field work, as they have established trust with gatekeepers in those locations. I’m still doubtful an MSW student interning at the middle school would be able to get consent for this study, but they probably have a better chance than a researcher with no relationship to the school. In the case where the population (children who self-harm) are too vulnerable, student researchers may collect data from people who have secondary knowledge about the topic. For example, the principal may be more willing to let you talk to teachers or staff, rather than children. I commonly see student projects that focus on studying practitioners rather than clients for this reason.

Stakeholders

In some cases, researchers and gatekeepers partner on a research project. When this happens, the gatekeepers become stakeholders. Stakeholders are individuals or groups who have an interest in the outcome of the study you conduct. As you think about your project, consider whether there are formal advisory groups or boards (like a school board) or advocacy organizations who already serve or work with your target population. Approach them as experts an ask for their review of your study to see if there are any perspectives or details you missed that would make your project stronger.

There are many advantages to partnering with stakeholders to complete a research project together. Continuing with our example on self-harm in schools, in order to obtain access to interview children at a middle school, you will have to consider other stakeholders’ goals. School administrators also want to help students struggling with self-harm, so they may want to use the results to form new programs. But they may also need to avoid scandal and panic if the results show high levels of self-harm. Most likely, they want to provide support to students without making the problem worse. By bringing in school administrators as stakeholders, you can better understand what the school is currently doing to address the issue and get an informed perspective on your project’s questions. Negotiating the boundaries of a stakeholder relationship requires strong meso-level practice skills.

Of course, partnering with administrators probably sounds quite a bit easier than bringing on board the next group of stakeholders—parents. It’s not ethical to ask children to participate in a study without their parents’ consent. We will review the parameters of parental and child consent in Chapter 5. Parents may be understandably skeptical of a researcher who wants to talk to their child about self-harm, and they may fear potential harms to the child and family from your study. Would you let a researcher you didn’t know interview your children about a very sensitive issue?

Social work research must often satisfy multiple stakeholders. This is especially true if a researcher receives a grant to support the project, as the funder has goals it wants to accomplish by funding the research project. Your MSW program and university are also stakeholders in your project. When you conduct research, it reflects on your school. If you discover something of great importance, your school looks good. If you harm someone, they may be liable. Your university likely has opportunities for you to share your research with the campus community, and may have incentives or grant programs for student researchers. Your school also provides you with support through instruction and access to resources like the library and data analysis software.

Target population

So far, we’ve talked about access in terms of gatekeepers and stakeholders. Let’s assume all of those people agree that your study should proceed. But what about the people in the target population? They are the most important stakeholder of all! Think about the children in our proposed study on self-harm. How open do you think they would be to talking to you about such a sensitive issue? Would they consent to talk to you at all?

Maybe you are thinking about simply asking clients on your caseload. As we talked about before, leveraging existing relationships created through field work can help with accessing your target population. However, they introduce other ethical issues for researchers. Asking clients on your caseload or at your agency to participate in your project creates a dual relationship between you and your client. What if you learn something in the research project that you want to share with your clinical team? More importantly, would your client feel uncomfortable if they do not consent to your study? Social workers have power over clients, and any dual relationship would require strict supervision in the rare case it was allowed.

Resources and scope

Let’s assume everyone consented to your project and you have adequately addressed any ethical issues with gatekeepers, stakeholders, and your target population. That means everything is ready to go, right? Not quite yet. As a researcher, you will need to carry out the study you propose to do. Depending on how big or how small your proposed project is, you’ll need a little or a lot of resources. Generally, student projects should err on the side of small and simple. We will discuss the limitations of this advice in section 2.5.

Raw data

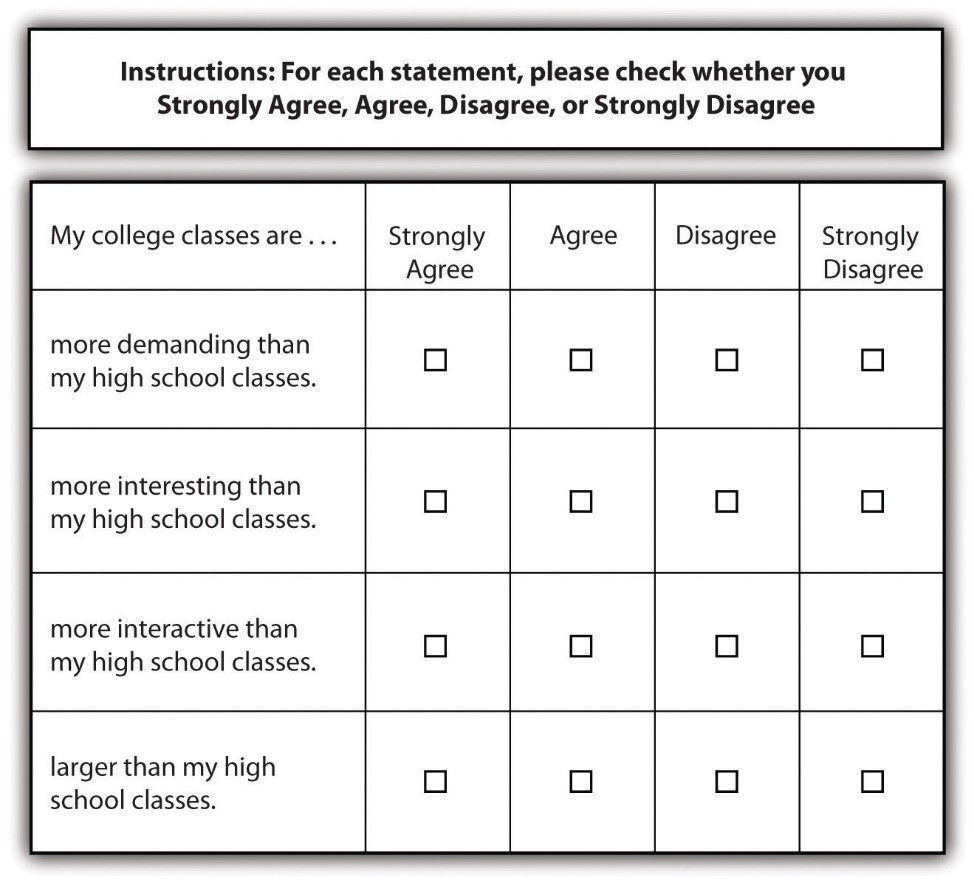

One thing that all projects need is raw data. It’s extremely important to note that raw data is not just the information you read in journal articles and books. Every year, I get at least one student research proposal that simply proposes to read articles. It’s a very understandable mistake to make. Most graduate school assignments are simply to read about a topic and write a paper. A research project involves doing the same kind of research that the authors of journal articles do when they conduct quantitative or qualitative studies. Raw data can come in may forms. Very often in social science research, raw data includes the responses to a survey or transcripts of interviews and focus groups, but raw data can also include experimental results, diary entries, art, or other data points that social scientists use in analyzing the world.

As the above examples illustrate, some social work researchers do not collect raw data of their own, but instead use secondary data analysis to analyze raw data that has been shared by other researchers . One common source of raw data in student projects from their internship or employer. By looking at client charts or data from previous grant reports or program evaluations, you can use raw data already collected by your agency to answer your research question. You can also use data that was not gathered by a scientist but is publicly available. For example, you might analyze blog entries, movies, YouTube videos, songs, or other pieces of media. Whether a researcher should use secondary data or collect their own raw data is an important choice which we will discuss in greater detail in section 2.4. Nevertheless, without raw data there can be no research project. Reading the literature about your topic is only the first step in a research project.

Time

Time is a student’s most precious resource. MSW students are overworked and underpaid, so it is important to be upfront with yourself about the time needed to answer your question. Every hour spent on your research project is not spent doing other things. Make sure that your proposal won’t require you to spend years collecting and analyzing data. Think realistically about the timeline for this research project. If you propose to interview fifty mental health professionals in their offices in your community about your topic, make sure you can dedicate fifty hours to conduct those interviews, account for travel time, and think about how long it will take to transcribe and analyze those interviews.

- What is reasonable for you to do over this semester and potentially another semester of advanced research methods?

- How many hours each week can you dedicate to this project considering what you have to do for other MSW courses, your internship and job, as well as family or social responsibilities?

In many cases, focusing your working question on something simple, specific, and clear can help avoid time issues in research projects. Another thing that can delay a research project is receiving approval from the institutional review board (IRB), the research ethics committee at your university. If your study may cause harm to people who participate in it, you may have to formally propose your study to the IRB and get their approval before gathering your data. A well-prepared study is likely to gain IRB approval with minimal revisions needed, but the process can take weeks to complete and must be done before data collection can begin. We will address the ethical obligations of researchers in greater detail in Chapter 5.

Money

Most research projects cost some amount of money, but for student projects, most of that money is already paid. You paid for access to a university library that provides you with all of the journals, books, and other sources you might need. You paid for a computer for homework and may use your car to drive to go to class or collect your data. You paid for this class. You are not expected to spend any additional money on your student research project.

However, it is always worth looking to see if there are grant opportunities to support student research in your school or program. Often, these will cover small expenses like travel or incentives for people who participate in the study. Alternately, you could use university grant funds to travel to academic conferences to present on your findings and network with other students, practitioners, and researchers. Chapter 24 reviews academic conferences relevant to social work practice and education with a focus on the United States.

Knowledge, competence, and skills

Another student resource is knowledge. By engaging with the literature on your topic and learning the content in your research methods class, you will learn how to study your topic using social scientific research methods. The core social work value of competence is key here. Here’s an example from my work on one of my former university’s research ethics board. A student from the design department wanted to study suicide by talking to college students in a suicide prevention campus group. While meeting with the student researcher, someone on the board asked what she would do if one of the students in her study disclosed that they were currently suicidal. The researcher responded that she never considered that possibility, and that she envisioned a more “fun” discussion. We hope this example set off alarm bells for you, as it did for the review board.

Clearly, researchers need to know enough about their target population in order to conduct ethical research. Because students usually have little experience in the research world, their projects should pose fewer potential risks to participants. That means posing few, if any, questions about sensitive issues, such as trauma. A common way around this challenge is by collecting data from less vulnerable populations such as practitioners or administrators who have second-hand knowledge of target populations based on professional relationships.

Knowledge and the social work value of ethical competence go hand in hand. We see the issue of competence often in student projects if their question is about whether an intervention, for example dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), is effective. A student would have to be certified in DBT in order to gather raw data by practicing it with clients and tracking their progress. That’s well outside the scope of practice competency for an MSW student and better suited to a licensed practitioner. It would be more ethical and feasible for a student researcher to analyze secondary data from a practitioner certified to use DBT or analyze raw data from another researcher’s study.

If your working question asks about which interventions are effective for a problem, don’t panic. Often questions about effectiveness are good places to start, but the project will have to shift in order be workable for a student. Perhaps the student would like to learn more about the cost of getting trained in DBT, which aspects of it practitioners find the most useful, whether insurance companies will reimburse for it, or other topics that require fewer resources to answer. In the process of investigating a smaller project like this, you will learn about the effectiveness of DBT by reading the scholarly literature but the actual research project will be smaller and more feasible to conduct as a student.

Another idea to keep in mind is the level of data collection and analysis skills you will gain during your MSW program. Most MSW programs will seek to give you the basics of quantitative and qualitative research. However, there are limits to what your courses will cover just as there are limits to what we could include in this textbook. If you feel your project may require specific education on data collection or analysis techniques, it’s important to reach out to your professor to see if it is feasible for you to gain that knowledge before conducting your study. For example, you may need to take an advanced statistics course or an independent study on community-engaged research in order to competently complete your project.

In summary, here are a few questions you should ask yourself about your project to make sure it’s feasible. While we present them early on in the research process (we’re only in Chapter 2), these are certainly questions you should ask yourself throughout the proposal writing process. We will revisit feasibility again in Chapter 9 when we work on finalizing your research question.

- Do you have access to the data you need or can you collect the data you need?

- Will you be able to get consent from stakeholders, gatekeepers, and your target population?

- Does your project pose risk to individuals through direct harm, dual relationships, or breaches in confidentiality?

- Are you competent enough to complete the study?

- Do you have the resources and time needed to carry out the project?

Key Takeaways

- People will have to say “yes” to your research project. Evaluate whether your project might have gatekeepers or potential stakeholders. They may control access to data or potential participants.

- Researchers need raw data such as survey responses, interview transcripts, or client charts. Your research project must involve more than looking at the analyses conducted by other researchers, as the literature review is only the first step of a research project.

- Make sure you have enough resources (time, money, and knowledge) to complete your research project during your MSW program.

Exercises

Think about how you might answer your question by collecting your own data.

- Identify any gatekeepers and stakeholders you might need to contact.

- Do you think it is likely you will get access to the people or records you need for your study?

Describe any potential harm that could come to people who participate in your study.

- Would the benefits of your study outweigh the risks?

2.4 Raw data

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify potential sources of available data

- Weigh the challenges and benefits of collecting your own data

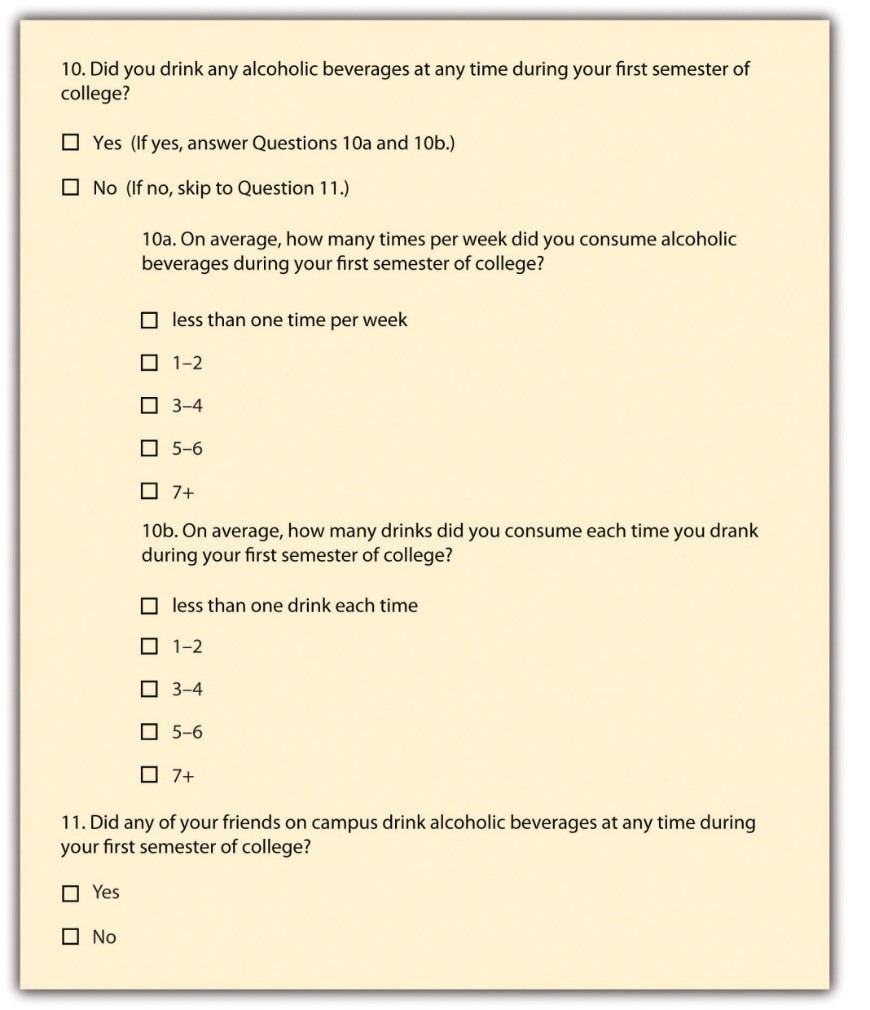

In our previous section, we addressed some of the challenges researchers face in collecting and analyzing raw data. Just as a reminder, raw data are unprocessed, unanalyzed data that researchers analyze using social science research methods. It is not just the statistics or qualitative themes in journal articles. It is the actual data from which those statistical outputs or themes are derived (e.g., interview transcripts or survey responses).

There are two approaches to getting raw data. First, students can analyze data that are publicly available or from agency records. Using secondary data like this can make projects more feasible, but you may not find existing data that are useful for answering your working question. For that reason, many students gather their own raw data. As we discussed in the previous section, potential harms that come from addressing sensitive topics mean that surveys and interviews of practitioners or other less-vulnerable populations may be the most feasible and ethical way to approach data collection.

Using secondary data

Within the agency setting, there are two main sources of raw data. One option is to examine client charts. For example, if you wanted to know if substance use was related to parental reunification for youth in foster care, you could look at client files and compare how long it took for families with differing levels of substance use to be reunified. You will have to negotiate with the agency the degree to which your analysis can be public. Agencies may be okay with you using client files for a class project but less comfortable with you presenting your findings at a city council meeting. When analyzing data from your agency, you will have to manage a stakeholder relationship.

Another great example from my class this year was a student who used existing program evaluations at their agency as raw data in her student research project. If you are practicing at a grant funded agency, administrators and clinicians are likely producing data for grant reporting. Your agency may consent to have you look at the raw data and run your own analysis. Larger agencies may also conduct internal research—for example, surveying employees or clients about new initiatives. These, too, can be good sources of available data. Generally, if your agency has already collected the data, you can ask to use them. Again, it is important to be clear on the boundaries and expectations of your agency. And don’t be angry if they say no!

Some agencies, usually government agencies, publish their data in formal reports. You could take a look at some of the websites for county or state agencies to see if there are any publicly available data relevant to your research topic. As an example, perhaps there are annual reports from the state department of education that show how seclusion and restraint is disproportionately applied to Black children with disabilities, as students found in Virginia. In my class last year, one student matched public data from our city’s map of criminal incidents with historically redlined neighborhoods. For this project, she is using publicly available data from Mapping Inequality, which digitized historical records of redlined housing communities and the Roanoke, VA crime mapping webpage. By matching historical data on housing redlining with current crime records, she is testing whether redlining still impacts crime to this day.

Not all public data are easily accessible, though. The student in the previous example was lucky that scholars had digitized the records of how Virginia cities were redlined by race. Sources of historical data are often located in physical archives, rather than digital archives. If your project uses historical data in an archive, it would require you to physically go to the archive in order to review the data. Unless you have a travel budget, you may be limited to the archival data in your local libraries and government offices. Similarly, government data may have to be requested from an agency, which can take time. If the data are particularly sensitive or if the department would have to dedicate a lot of time to your request, you may have to file a Freedom of Information Act request. This process can be time-consuming, and in some cases, it will add financial cost to your study.

Another source of secondary data is shared by researchers as part of the publication and review process. There is a growing trend in research to publicly share data so others can verify your results and attempt to replicate your study. In more recent articles, you may notice links to data provided by the researcher. Often, these have been de-identified by eliminating some information that could lead to violations of confidentiality. You can browse through the data repositories in Table 2.1 to find raw data to analyze. Make sure that you pick a data set with thorough and easy to understand documentation. You may also want to use Google’s dataset search which indexes some of the websites below as well as others in a very intuitive and easy to use way.

| Organizational home | Focus/topic | Data | Web address |

| National Opinion Research Center | General Social Survey; demographic, behavioral, attitudinal, and special interest questions; national sample | Quantitative | https://gss.norc.org/ |

| Carolina Population Center | Add Health; longitudinal social, economic, psychological, and physical well-being of cohort in grades 7–12 in 1994 | Quantitative | http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth |

| Center for Demography of Health and Aging | Wisconsin Longitudinal Study; life course study of cohorts who graduated from high school in 1957 | Quantitative | https://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/ |

| Institute for Social & Economic Research | British Household Panel Survey; longitudinal study of British lives and well- being | Quantitative | https://www.iser.essex.ac.uk/bhps |

| International Social Survey Programme | International data similar to GSS | Quantitative | http://www.issp.org/ |

| The Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University | Large archive of written data, audio, and video focused on many topics | Quantitative and qualitative | http://dvn.iq.harvard.edu/dvn/dv/mra |

| Institute for Research on Women and Gender | Global Feminisms Project; interview transcripts and oral histories on feminism and women’s activism | Qualitative | https://globalfeminisms.umich.edu/ |

| Oral History Office | Descriptions and links to numerous oral history archives | Qualitative | https://archives.lib.uconn.edu/islandora/ object/20002%3A19840025 |

| UNC Wilson Library | Digitized manuscript collection from the Southern Historical Collection | Qualitative | http://dc.lib.unc.edu/ead/archivalhome.php? CISOROOT=/ead |

| Qualitative Data Repository | A repository of qualitative data that can be downloaded and annotated collaboratively with other researchers | Qualitative | https://qdr.syr.edu/ |

Ultimately, you will have to weigh the strengths and limitations of using secondary data on your own. Engel and Schutt (2016, p. 327)[1] propose six questions to ask before using secondary data:

- What were the agency’s or researcher’s goals in collecting the data?

- What data were collected, and what were they intended to measure?

- When was the information collected?

- What methods were used for data collection? Who was responsible for data collection, and what were their qualifications? Are they available to answer questions about the data?

- How is the information organized (by date, individual, family, event, etc.)? Are identifiers used to indicate different types of data available?

- What is known about the success of the data collection effort? How are missing data indicated and treated? What kind of documentation is available? How consistent are the data with data available from other sources?

In this section, we’ve talked about data as though it is always collected by scientists and professionals. But that’s definitely not the case! Think more broadly about sources of data that are already out there in the world. Perhaps you want to examine the different topics mentioned in the past 10 State of the Union addresses by the President. One of my students this past semester is examining whether the websites and public information about local health and mental health agencies use gender-inclusive language. People share their experiences through blogs, social media posts, videos, performances, among countless other sources of data. When you think broadly about data, you’ll be surprised how much you can answer with available data.

Collecting your own raw data

The primary benefit of collecting your own data is that it allows you to collect and analyze the specific data you are looking for, rather than relying on what other people have shared. You can make sure the right questions are asked to the right people. For a student project, data collection is going to look a little different than what you read in most journal articles. Established researchers probably have access to more resources than you do, and as a result, are able to conduct more complicated studies. Student projects tend to be smaller in scope. This isn’t necessarily a limitation. Student projects are often the first step in a long research trajectory in which the same topic is studied in increasing detail and sophistication over time.

Students in my class often propose to survey or interview practitioners. The focus of these projects should be about the practice of social work and the study will uncover how practitioners understand what they do. Surveys of practitioners often test whether responses to questions are related to each other. For example, you could propose to examine whether someone’s length of time in practice was related to the type of therapy they use or their level of burnout. Interviews or focus groups can also illuminate areas of practice. A student in my class proposed to conduct focus groups of individuals in different helping professions in order to understand how they viewed the process of leaving an abusive partner. She suspected that people from different disciplines would make unique assumptions about the survivor’s choices.

It’s worth remembering here that you need to have access to practitioners, as we discussed in the previous section. Resourceful students will look at publicly available databases of practitioners, draw from agency and personal contacts, or post in public forums like Facebook groups. Consent from gatekeepers is important, and as we described earlier, you and your agency may be interested in collaborating on a project. Bringing your agency on board as a stakeholder in your project may allow you access to company email lists or time at staff meetings as well as access to practitioners. One of our students last year partnered with her internship placement at a local hospital to measure the burnout of that nurses experienced in their department. Her project helped the agency identify which departments may need additional support.

Another possible way you could collect data is by partnering with your agency on evaluating an existing program. Perhaps they want you to evaluate the early stage of a program to see if it’s going as planned and if any changes need to be made. Maybe there is an aspect of the program they haven’t measured but would like to, and you can fill that gap for them. Collaborating with agency partners in this way can be a challenge, as you must negotiate roles, get stakeholder buy-in, and manage the conflicting time schedules of field work and research work. At the same time, it allows you to make your work immediately relevant to your specific practice and client population.

In summary, many student projects fall into one of the following categories. These aren’t your only options! But they may be helpful in thinking about what students projects can look like.

- Analyzing chart or program evaluations at an agency

- Analyzing existing data from an agency, government body, or other public source

- Analyzing popular media or cultural artifacts

- Surveying or interviewing practitioners, administrators, or other less-vulnerable groups

- Conducting a program evaluation in collaboration with an agency

Key Takeaways

- All research projects require analyzing raw data.

- Student projects often analyze available data from agencies, government, or public sources. Doing so allows students to avoid the process of recruiting people to participate in their study. This makes projects more feasible but limits what you can study to the data that are already available to you.

- Student projects should avoid potentially harmful or sensitive topics when surveying or interviewing clients and other vulnerable populations. Since many social work topics are sensitive, students often collect data from less-vulnerable populations such as practitioners and administrators.

Exercises

- Describe the difference between raw data and the results of research articles.

- Identify potential sources of secondary data that might help you answer your working question.

- Consider browsing around the data repositories in Table 2.1.

- Identify one of the common types of student projects (e.g., surveys of practitioners) and how conducting a similar project might help you answer your working question.

- Engel, R. J. & Schutt, R. K. (2016). The practice of research in social work (4th ed.). Washington, DC: SAGE Publishing. ↵

when researchers use both quantitative and qualitative methods in a project

Chapter Outline

- Developing your theoretical framework

- Conceptual definitions

- Inductive & deductive reasoning

- Nomothetic causal explanations

Content warning: examples in this chapter include references to sexual harassment, domestic violence, gender-based violence, the child welfare system, substance use disorders, neonatal abstinence syndrome, child abuse, racism, and sexism.

11.1 Developing your theoretical framework

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Differentiate between theories that explain specific parts of the social world versus those that are more broad and sweeping in their conclusions

- Identify the theoretical perspectives that are relevant to your project and inform your thinking about it

- Define key concepts in your working question and develop a theoretical framework for how you understand your topic.

Theories provide a way of looking at the world and of understanding human interaction. Paradigms are grounded in big assumptions about the world—what is real, how do we create knowledge—whereas theories describe more specific phenomena. Well, we are still oversimplifying a bit. Some theories try to explain the whole world, while others only try to explain a small part. Some theories can be grouped together based on common ideas but retain their own individual and unique features. Our goal is to help you find a theoretical framework that helps you understand your topic more deeply and answer your working question.

Theories: Big and small

In your human behavior and the social environment (HBSE) class, you were introduced to the major theoretical perspectives that are commonly used in social work. These are what we like to call big-T 'T'heories. When you read about systems theory, you are actually reading a synthesis of decades of distinct, overlapping, and conflicting theories that can be broadly classified within systems theory. For example, within systems theory, some approaches focus more on family systems while others focus on environmental systems, though the core concepts remain similar.

Different theorists define concepts in their own way, and as a result, their theories may explore different relationships with those concepts. For example, Deci and Ryan's (1985)[1] self-determination theory discusses motivation and establishes that it is contingent on meeting one's needs for autonomy, competency, and relatedness. By contrast, ecological self-determination theory, as written by Abery & Stancliffe (1996),[2] argues that self-determination is the amount of control exercised by an individual over aspects of their lives they deem important across the micro, meso, and macro levels. If self-determination were an important concept in your study, you would need to figure out which of the many theories related to self-determination helps you address your working question.

Theories can provide a broad perspective on the key concepts and relationships in the world or more specific and applied concepts and perspectives. Table 7.2 summarizes two commonly used lists of big-T Theoretical perspectives in social work. See if you can locate some of the theories that might inform your project.

| Payne's (2014)[3] practice theories | Hutchison's (2014)[4] theoretical perspectives |

| Psychodynamic | Systems |

| Crisis and task-centered | Conflict |

| Cognitive-behavioral | Exchange and choice |

| Systems/ecological | Social constructionist |

| Macro practice/social development/social pedagogy | Psychodynamic |

| Strengths/solution/narrative | Developmental |

| Humanistic/existential/spiritual | Social behavioral |

| Critical | Humanistic |

| Feminist | |

| Anti-discriminatory/multi-cultural sensitivity |

Competing theoretical explanations

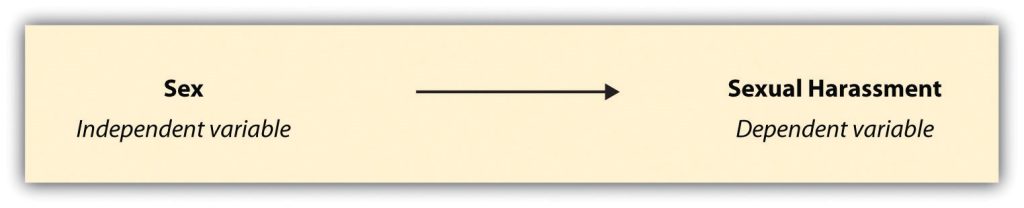

Within each area of specialization in social work, there are many other theories that aim to explain more specific types of interactions. For example, within the study of sexual harassment, different theories posit different explanations for why harassment occurs.

One theory, first developed by criminologists, is called routine activities theory. It posits that sexual harassment is most likely to occur when a workplace lacks unified groups and when potentially vulnerable targets and motivated offenders are both present (DeCoster, Estes, & Mueller, 1999).[5]

Other theories of sexual harassment, called relational theories, suggest that one's existing relationships are the key to understanding why and how workplace sexual harassment occurs and how people will respond when it does occur (Morgan, 1999).[6] Relational theories focus on the power that different social relationships provide (e.g., married people who have supportive partners at home might be more likely than those who lack support at home to report sexual harassment when it occurs).

Finally, feminist theories of sexual harassment take a different stance. These theories posit that the organization of our current gender system, wherein those who are the most masculine have the most power, best explains the occurrence of workplace sexual harassment (MacKinnon, 1979).[7] As you might imagine, which theory a researcher uses to examine the topic of sexual harassment will shape the questions asked about harassment. It will also shape the explanations the researcher provides for why harassment occurs.

For a graduate student beginning their study of a new topic, it may be intimidating to learn that there are so many theories beyond what you’ve learned in your theory classes. What’s worse is that there is no central database of theories on your topic. However, as you review the literature in your area, you will learn more about the theories scientists have created to explain how your topic works in the real world. There are other good sources for theories, in addition to journal articles. Books often contain works of theoretical and philosophical importance that are beyond the scope of an academic journal. Do a search in your university library for books on your topic, and you are likely to find theorists talking about how to make sense of your topic. You don't necessarily have to agree with the prevailing theories about your topic, but you do need to be aware of them so you can apply theoretical ideas to your project.

Applying big-T theories to your topic

The key to applying theories to your topic is learning the key concepts associated with that theory and the relationships between those concepts, or propositions. Again, your HBSE class should have prepared you with some of the most important concepts from the theoretical perspectives listed in Table 7.2. For example, the conflict perspective sees the world as divided into dominant and oppressed groups who engage in conflict over resources. If you were applying these theoretical ideas to your project, you would need to identify which groups in your project are considered dominant or oppressed groups, and which resources they were struggling over. This is a very general example. Challenge yourself to find small-t theories about your topic that will help you understand it in much greater detail and specificity. If you have chosen a topic that is relevant to your life and future practice, you will be doing valuable work shaping your ideas towards social work practice.

Integrating theory into your project can be easy, or it can take a bit more effort. Some people have a strong and explicit theoretical perspective that they carry with them at all times. For me, you'll probably see my work drawing from exchange and choice, social constructionist, and critical theory. Maybe you have theoretical perspectives you naturally employ, like Afrocentric theory or person-centered practice. If so, that's a great place to start since you might already be using that theory (even subconsciously) to inform your understanding of your topic. But if you aren't aware of whether you are using a theoretical perspective when you think about your topic, try writing a paragraph off the top of your head or talking with a friend explaining what you think about that topic. Try matching it with some of the ideas from the broad theoretical perspectives from Table 7.2. This can ground you as you search for more specific theories. Some studies are designed to test whether theories apply the real world while others are designed to create new theories or variations on existing theories. Consider which feels more appropriate for your project and what you want to know.

Another way to easily identify the theories associated with your topic is to look at the concepts in your working question. Are these concepts commonly found in any of the theoretical perspectives in Table 7.2? Take a look at the Payne and Hutchison texts and see if any of those look like the concepts and relationships in your working question or if any of them match with how you think about your topic. Even if they don't possess the exact same wording, similar theories can help serve as a starting point to finding other theories that can inform your project. Remember, HBSE textbooks will give you not only the broad statements of theories but also sources from specific theorists and sub-theories that might be more applicable to your topic. Skim the references and suggestions for further reading once you find something that applies well.

Exercises

Choose a theoretical perspective from Hutchison, Payne, or another theory textbook that is relevant to your project. Using their textbooks or other reputable sources, identify :

- At least five important concepts from the theory

- What relationships the theory establishes between these important concepts (e.g., as x increases, the y decreases)

- How you can use this theory to better understand the concepts and variables in your project?

Developing your own theoretical framework

Hutchison's and Payne's frameworks are helpful for surveying the whole body of literature relevant to social work, which is why they are so widely used. They are one framework, or way of thinking, about all of the theories social workers will encounter that are relevant to practice. Social work researchers should delve further and develop a theoretical or conceptual framework of their own based on their reading of the literature. In Chapter 8, we will develop your theoretical framework further, identifying the cause-and-effect relationships that answer your working question. Developing a theoretical framework is also instructive for revising and clarifying your working question and identifying concepts that serve as keywords for additional literature searching. The greater clarity you have with your theoretical perspective, the easier each subsequent step in the research process will be.

Getting acquainted with the important theoretical concepts in a new area can be challenging. While social work education provides a broad overview of social theory, you will find much greater fulfillment out of reading about the theories related to your topic area. We discussed some strategies for finding theoretical information in Chapter 3 as part of literature searching. To extend that conversation a bit, some strategies for searching for theories in the literature include:

- Using keywords like "theory," "conceptual," or "framework" in queries to better target the search at sources that talk about theory.

- Consider searching for these keywords in the title or abstract, specifically

- Looking at the references and cited by links within theoretical articles and textbooks

- Looking at books, edited volumes, and textbooks that discuss theory

- Talking with a scholar on your topic, or asking a professor if they can help connect you to someone

- Looking at how researchers use theory in their research projects

- Nice authors are clear about how they use theory to inform their research project, usually in the introduction and discussion section.

- Starting with a Big-T Theory and looking for sub-theories or specific theorists that directly address your topic area

- For example, from the broad umbrella of systems theory, you might pick out family systems theory if you want to understand the effectiveness of a family counseling program.

It's important to remember that knowledge arises within disciplines, and that disciplines have different theoretical frameworks for explaining the same topic. While it is certainly important for the social work perspective to be a part of your analysis, social workers benefit from searching across disciplines to come to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. Reaching across disciplines can provide uncommon insights during conceptualization, and once the study is completed, a multidisciplinary researcher will be able to share results in a way that speaks to a variety of audiences. A study by An and colleagues (2015)[8] uses game theory from the discipline of economics to understand problems in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. In order to receive TANF benefits, mothers must cooperate with paternity and child support requirements unless they have "good cause," as in cases of domestic violence, in which providing that information would put the mother at greater risk of violence. Game theory can help us understand how TANF recipients and caseworkers respond to the incentives in their environment, and highlight why the design of the "good cause" waiver program may not achieve its intended outcome of increasing access to benefits for survivors of family abuse.

Of course, there are natural limits on the depth with which student researchers can and should engage in a search for theory about their topic. At minimum, you should be able to draw connections across studies and be able to assess the relative importance of each theory within the literature. Just because you found one article applying your theory (like game theory, in our example above) does not mean it is important or often used in the domestic violence literature. Indeed, it would be much more common in the family violence literature to find psychological theories of trauma, feminist theories of power and control, and similar theoretical perspectives used to inform research projects rather than game theory, which is equally applicable to survivors of family violence as workers and bosses at a corporation. Consider using the Cited By feature to identify articles, books, and other sources of theoretical information that are seminal or well-cited in the literature. Similarly, by using the name of a theory in the keywords of a search query (along with keywords related to your topic), you can get a sense of how often the theory is used in your topic area. You should have a sense of what theories are commonly used to analyze your topic, even if you end up choosing a different one to inform your project.

Theories that are not cited or used as often are still immensely valuable. As we saw before with TANF and "good cause" waivers, using theories from other disciplines can produce uncommon insights and help you make a new contribution to the social work literature. Given the privileged position that the social work curriculum places on theories developed by white men, students may want to explore Afrocentricity as a social work practice theory (Pellebon, 2007)[9] or abolitionist social work (Jacobs et al., 2021)[10] when deciding on a theoretical framework for their research project that addresses concepts of racial justice. Start with your working question, and explain how each theory helps you answer your question. Some explanations are going to feel right, and some concepts will feel more salient to you than others. Keep in mind that this is an iterative process. Your theoretical framework will likely change as you continue to conceptualize your research project, revise your research question, and design your study.

By trying on many different theoretical explanations for your topic area, you can better clarify your own theoretical framework. Some of you may be fortunate enough to find theories that match perfectly with how you think about your topic, are used often in the literature, and are therefore relatively straightforward to apply. However, many of you may find that a combination of theoretical perspectives is most helpful for you to investigate your project. For example, maybe the group counseling program for which you are evaluating client outcomes draws from both motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. In order to understand the change happening in the client population, you would need to know each theory separately as well as how they work in tandem with one another. Because theoretical explanations and even the definitions of concepts are debated by scientists, it may be helpful to find a specific social scientist or group of scientists whose perspective on the topic you find matches with your understanding of the topic. Of course, it is also perfectly acceptable to develop your own theoretical framework, though you should be able to articulate how your framework fills a gap within the literature.

If you are adapting theoretical perspectives in your study, it is important to clarify the original authors' definitions of each concept. Jabareen (2009)[11] offers that conceptual frameworks are not merely collections of concepts but, rather, constructs in which each concept plays an integral role.[12] A conceptual framework is a network of linked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. Each concept in a conceptual framework plays an ontological or epistemological role in the framework, and it is important to assess whether the concepts and relationships in your framework make sense together. As your framework takes shape, you will find yourself integrating and grouping together concepts, thinking about the most important or least important concepts, and how each concept is causally related to others.

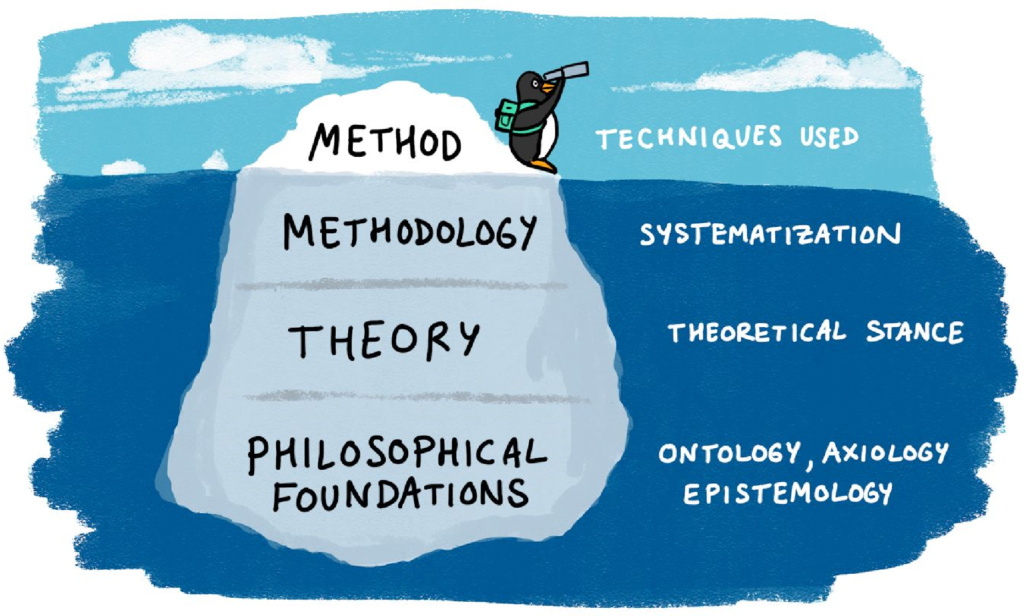

Much like paradigm, theory plays a supporting role for the conceptualization of your research project. Recall the ice float from Figure 7.1. Theoretical explanations support the design and methods you use to answer your research question. In student projects that lack a theoretical framework, I often see the biases and errors in reasoning that we discussed in Chapter 1 that get in the way of good social science. That's because theories mark which concepts are important, provide a framework for understanding them, and measure their interrelationships. If you are missing this foundation, you will operate on informal observation, messages from authority, and other forms of unsystematic and unscientific thinking we reviewed in Chapter 1.

Theory-informed inquiry is incredibly helpful for identifying key concepts and how to measure them in your research project, but there is a risk in aligning research too closely with theory. The theory-ladenness of facts and observations produced by social science research means that we may be making our ideas real through research. This is a potential source of confirmation bias in social science. Moreover, as Tan (2016)[13] demonstrates, social science often proceeds by adopting as true the perspective of Western and Global North countries, and cross-cultural research is often when ethnocentric and biased ideas are most visible. In her example, a researcher from the West studying teacher-centric classrooms in China that rely partially on rote memorization may view them as less advanced than student-centered classrooms developed in a Western country simply because of Western philosophical assumptions about the importance of individualism and self-determination. Developing a clear theoretical framework is a way to guard against biased research, and it will establish a firm foundation on which you will develop the design and methods for your study.

Key Takeaways

- Just as empirical evidence is important for conceptualizing a research project, so too are the key concepts and relationships identified by social work theory.

- Using theory your theory textbook will provide you with a sense of the broad theoretical perspectives in social work that might be relevant to your project.

- Try to find small-t theories that are more specific to your topic area and relevant to your working question.

Exercises

- In Chapter 2, you developed a concept map for your proposal. Take a moment to revisit your concept map now as your theoretical framework is taking shape. Make any updates to the key concepts and relationships in your concept map.

. If you need a refresher, we have embedded a short how-to video from the University of Guelph Library (CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0) that we also used in Chapter 2.

11.2 Conceptual definitions

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Define measurement and conceptualization

- Apply Kaplan’s three categories to determine the complexity of measuring a given variable

- Identify the role previous research and theory play in defining concepts

- Distinguish between unidimensional and multidimensional concepts

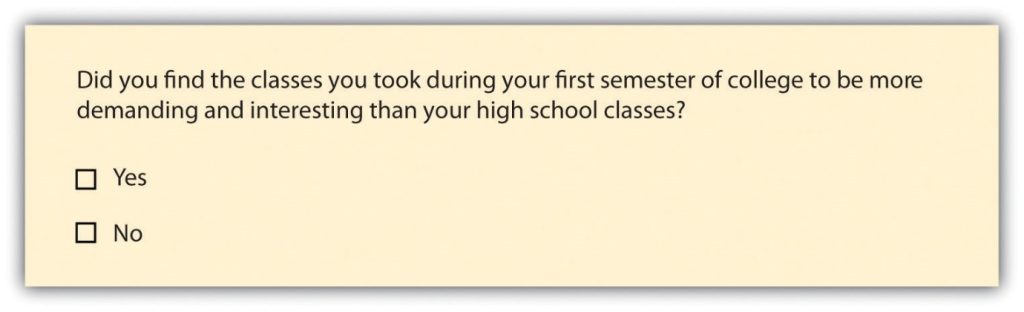

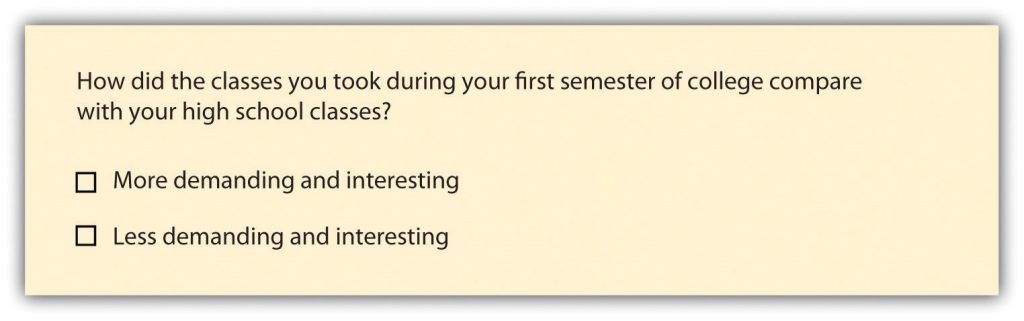

- Critically apply reification to how you conceptualize the key variables in your research project

In social science, when we use the term measurement, we mean the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms in as clear and precise a way as possible. Of course, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using a measuring cup or spoon, but there are some basic tenets on which most social scientists agree when it comes to measurement. We’ll explore those, as well as some of the ways that measurement might vary depending on your unique approach to the study of your topic.

An important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. What it does require is a systematic procedure for assigning scores, meanings, and descriptions to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest. You can measure phenomena in many different ways, but you must be sure that how you choose to measure gives you information and data that lets you answer your research question. If you're looking for information about a person's income, but your main points of measurement have to do with the money they have in the bank, you're not really going to find the information you're looking for!

The question of what social scientists measure can be answered by asking yourself what social scientists study. Think about the topics you’ve learned about in other social work classes you’ve taken or the topics you’ve considered investigating yourself. Let’s consider Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner’s study (2011)[14] of first graders’ mental health. In order to conduct that study, Milkie and Warner needed to have some idea about how they were going to measure mental health. What does mental health mean, exactly? And how do we know when we’re observing someone whose mental health is good and when we see someone whose mental health is compromised? Understanding how measurement works in research methods helps us answer these sorts of questions.

As you might have guessed, social scientists will measure just about anything that they have an interest in investigating. For example, those who are interested in learning something about the correlation between social class and levels of happiness must develop some way to measure both social class and happiness. Those who wish to understand how well immigrants cope in their new locations must measure immigrant status and coping. Those who wish to understand how a person’s gender shapes their workplace experiences must measure gender and workplace experiences (and get more specific about which experiences are under examination). You get the idea. Social scientists can and do measure just about anything you can imagine observing or wanting to study. Of course, some things are easier to observe or measure than others.

Observing your variables

In 1964, philosopher Abraham Kaplan (1964)[15] wrote The Conduct of Inquiry, which has since become a classic work in research methodology (Babbie, 2010).[16] In his text, Kaplan describes different categories of things that behavioral scientists observe. One of those categories, which Kaplan called “observational terms,” is probably the simplest to measure in social science. Observational terms are the sorts of things that we can see with the naked eye simply by looking at them. Kaplan roughly defines them as conditions that are easy to identify and verify through direct observation. If, for example, we wanted to know how the conditions of playgrounds differ across different neighborhoods, we could directly observe the variety, amount, and condition of equipment at various playgrounds.

Indirect observables, on the other hand, are less straightforward to assess. In Kaplan's framework, they are conditions that are subtle and complex that we must use existing knowledge and intuition to define. If we conducted a study for which we wished to know a person’s income, we’d probably have to ask them their income, perhaps in an interview or a survey. Thus, we have observed income, even if it has only been observed indirectly. Birthplace might be another indirect observable. We can ask study participants where they were born, but chances are good we won’t have directly observed any of those people being born in the locations they report.

Sometimes the measures that we are interested in are more complex and more abstract than observational terms or indirect observables. Think about some of the concepts you’ve learned about in other social work classes—for example, ethnocentrism. What is ethnocentrism? Well, from completing an introduction to social work class you might know that it has something to do with the way a person judges another’s culture. But how would you measure it? Here’s another construct: bureaucracy. We know this term has something to do with organizations and how they operate but measuring such a construct is trickier than measuring something like a person’s income. The theoretical concepts of ethnocentrism and bureaucracy represent ideas whose meanings we have come to agree on. Though we may not be able to observe these abstractions directly, we can observe their components.

Kaplan referred to these more abstract things that behavioral scientists measure as constructs. Constructs are “not observational either directly or indirectly” (Kaplan, 1964, p. 55),[17] but they can be defined based on observables. For example, the construct of bureaucracy could be measured by counting the number of supervisors that need to approve routine spending by public administrators. The greater the number of administrators that must sign off on routine matters, the greater the degree of bureaucracy. Similarly, we might be able to ask a person the degree to which they trust people from different cultures around the world and then assess the ethnocentrism inherent in their answers. We can measure constructs like bureaucracy and ethnocentrism by defining them in terms of what we can observe.[18]

The idea of coming up with your own measurement tool might sound pretty intimidating at this point. The good news is that if you find something in the literature that works for you, you can use it (with proper attribution, of course). If there are only pieces of it that you like, you can reuse those pieces (with proper attribution and describing/justifying any changes). You don't always have to start from scratch!

Exercises

Look at the variables in your research question.

- Classify them as direct observables, indirect observables, or constructs.

- Do you think measuring them will be easy or hard?

- What are your first thoughts about how to measure each variable? No wrong answers here, just write down a thought about each variable.

Measurement starts with conceptualization

In order to measure the concepts in your research question, we first have to understand what we think about them. As an aside, the word concept has come up quite a bit, and it is important to be sure we have a shared understanding of that term. A concept is the notion or image that we conjure up when we think of some cluster of related observations or ideas. For example, masculinity is a concept. What do you think of when you hear that word? Presumably, you imagine some set of behaviors and perhaps even a particular style of self-presentation. Of course, we can’t necessarily assume that everyone conjures up the same set of ideas or images when they hear the word masculinity. While there are many possible ways to define the term and some may be more common or have more support than others, there is no universal definition of masculinity. What counts as masculine may shift over time, from culture to culture, and even from individual to individual (Kimmel, 2008). This is why defining our concepts is so important.\

Not all researchers clearly explain their theoretical or conceptual framework for their study, but they should! Without understanding how a researcher has defined their key concepts, it would be nearly impossible to understand the meaning of that researcher’s findings and conclusions. Back in Chapter 7, you developed a theoretical framework for your study based on a survey of the theoretical literature in your topic area. If you haven't done that yet, consider flipping back to that section to familiarize yourself with some of the techniques for finding and using theories relevant to your research question. Continuing with our example on masculinity, we would need to survey the literature on theories of masculinity. After a few queries on masculinity, I found a wonderful article by Wong (2010)[19] that analyzed eight years of the journal Psychology of Men & Masculinity and analyzed how often different theories of masculinity were used. Not only can I get a sense of which theories are more accepted and which are more marginal in the social science on masculinity, I am able to identify a range of options from which I can find the theory or theories that will inform my project.

Exercises

Identify a specific theory (or more than one theory) and how it helps you understand...

- Your independent variable(s).

- Your dependent variable(s).

- The relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Rather than completing this exercise from scratch, build from your theoretical or conceptual framework developed in previous chapters.

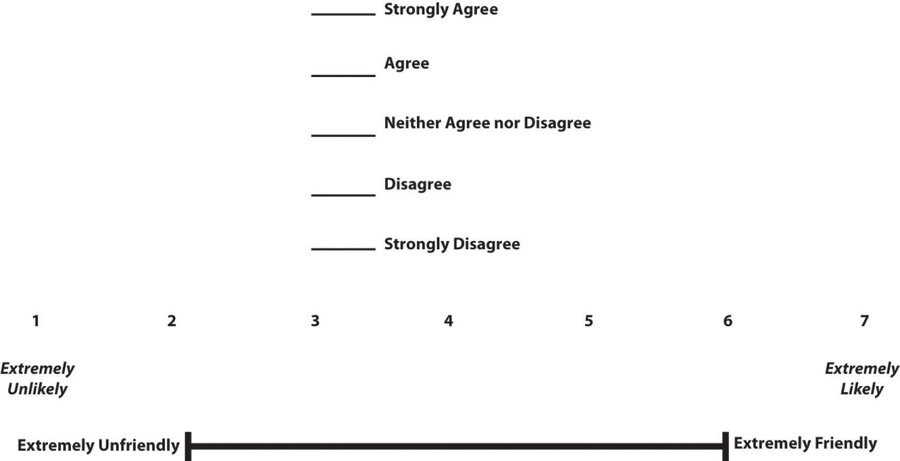

In quantitative methods, conceptualization involves writing out clear, concise definitions for our key concepts. These are the kind of definitions you are used to, like the ones in a dictionary. A conceptual definition involves defining a concept in terms of other concepts, usually by making reference to how other social scientists and theorists have defined those concepts in the past. Of course, new conceptual definitions are created all the time because our conceptual understanding of the world is always evolving.

Conceptualization is deceptively challenging—spelling out exactly what the concepts in your research question mean to you. Following along with our example, think about what comes to mind when you read the term masculinity. How do you know masculinity when you see it? Does it have something to do with men or with social norms? If so, perhaps we could define masculinity as the social norms that men are expected to follow. That seems like a reasonable start, and at this early stage of conceptualization, brainstorming about the images conjured up by concepts and playing around with possible definitions is appropriate. However, this is just the first step. At this point, you should be beyond brainstorming for your key variables because you have read a good amount of research about them

In addition, we should consult previous research and theory to understand the definitions that other scholars have already given for the concepts we are interested in. This doesn’t mean we must use their definitions, but understanding how concepts have been defined in the past will help us to compare our conceptualizations with how other scholars define and relate concepts. Understanding prior definitions of our key concepts will also help us decide whether we plan to challenge those conceptualizations or rely on them for our own work. Finally, working on conceptualization is likely to help in the process of refining your research question to one that is specific and clear in what it asks. Conceptualization and operationalization (next section) are where "the rubber meets the road," so to speak, and you have to specify what you mean by the question you are asking. As your conceptualization deepens, you will often find that your research question becomes more specific and clear.

If we turn to the literature on masculinity, we will surely come across work by Michael Kimmel, one of the preeminent masculinity scholars in the United States. After consulting Kimmel’s prior work (2000; 2008),[20] we might tweak our initial definition of masculinity. Rather than defining masculinity as “the social norms that men are expected to follow,” perhaps instead we’ll define it as “the social roles, behaviors, and meanings prescribed for men in any given society at any one time” (Kimmel & Aronson, 2004, p. 503).[21] Our revised definition is more precise and complex because it goes beyond addressing one aspect of men’s lives (norms), and addresses three aspects: roles, behaviors, and meanings. It also implies that roles, behaviors, and meanings may vary across societies and over time. Using definitions developed by theorists and scholars is a good idea, though you may find that you want to define things your own way.

As you can see, conceptualization isn’t as simple as applying any random definition that we come up with to a term. Defining our terms may involve some brainstorming at the very beginning. But conceptualization must go beyond that, to engage with or critique existing definitions and conceptualizations in the literature. Once we’ve brainstormed about the images associated with a particular word, we should also consult prior work to understand how others define the term in question. After we’ve identified a clear definition that we’re happy with, we should make sure that every term used in our definition will make sense to others. Are there terms used within our definition that also need to be defined? If so, our conceptualization is not yet complete. Our definition includes the concept of "social roles," so we should have a definition for what those mean and become familiar with role theory to help us with our conceptualization. If we don't know what roles are, how can we study them?

Let's say we do all of that. We have a clear definition of the term masculinity with reference to previous literature and we also have a good understanding of the terms in our conceptual definition...then we're done, right? Not so fast. You’ve likely met more than one man in your life, and you’ve probably noticed that they are not the same, even if they live in the same society during the same historical time period. This could mean there are dimensions of masculinity. In terms of social scientific measurement, concepts can be said to have multiple dimensions when there are multiple elements that make up a single concept. With respect to the term masculinity, dimensions could based on gender identity, gender performance, sexual orientation, etc.. In any of these cases, the concept of masculinity would be considered to have multiple dimensions.

While you do not need to spell out every possible dimension of the concepts you wish to measure, it is important to identify whether your concepts are unidimensional (and therefore relatively easy to define and measure) or multidimensional (and therefore require multi-part definitions and measures). In this way, how you conceptualize your variables determines how you will measure them in your study. Unidimensional concepts are those that are expected to have a single underlying dimension. These concepts can be measured using a single measure or test. Examples include simple concepts such as a person’s weight, time spent sleeping, and so forth.

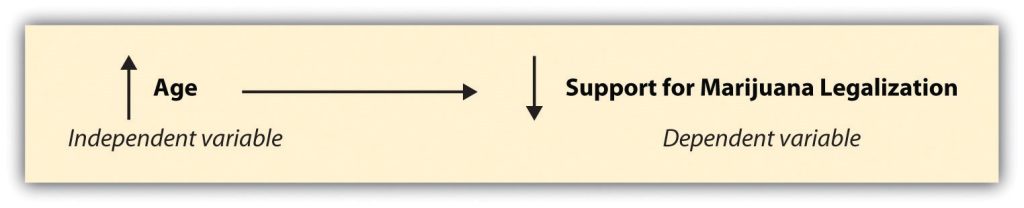

One frustrating this is that there is no clear demarcation between concepts that are inherently unidimensional or multidimensional. Even something as simple as age could be broken down into multiple dimensions including mental age and chronological age, so where does conceptualization stop? How far down the dimensional rabbit hole do we have to go? Researchers should consider two things. First, how important is this variable in your study? If age is not important in your study (maybe it is a control variable), it seems like a waste of time to do a lot of work drawing from developmental theory to conceptualize this variable. A unidimensional measure from zero to dead is all the detail we need. On the other hand, if we were measuring the impact of age on masculinity, conceptualizing our independent variable (age) as multidimensional may provide a richer understanding of its impact on masculinity. Finally, your conceptualization will lead directly to your operationalization of the variable, and once your operationalization is complete, make sure someone reading your study could follow how your conceptual definitions informed the measures you chose for your variables.

Exercises

Write a conceptual definition for your independent and dependent variables.

- Cite and attribute definitions to other scholars, if you use their words.

- Describe how your definitions are informed by your theoretical framework.

- Place your definition in conversation with other theories and conceptual definitions commonly used in the literature.

- Are there multiple dimensions of your variables?

- Are any of these dimensions important for you to measure?

Do researchers actually know what we're talking about?

Conceptualization proceeds differently in qualitative research compared to quantitative research. Since qualitative researchers are interested in the understandings and experiences of their participants, it is less important for them to find one fixed definition for a concept before starting to interview or interact with participants. The researcher’s job is to accurately and completely represent how their participants understand a concept, not to test their own definition of that concept.

If you were conducting qualitative research on masculinity, you would likely consult previous literature like Kimmel’s work mentioned above. From your literature review, you may come up with a working definition for the terms you plan to use in your study, which can change over the course of the investigation. However, the definition that matters is the definition that your participants share during data collection. A working definition is merely a place to start, and researchers should take care not to think it is the only or best definition out there.

In qualitative inquiry, your participants are the experts (sound familiar, social workers?) on the concepts that arise during the research study. Your job as the researcher is to accurately and reliably collect and interpret their understanding of the concepts they describe while answering your questions. Conceptualization of concepts is likely to change over the course of qualitative inquiry, as you learn more information from your participants. Indeed, getting participants to comment on, extend, or challenge the definitions and understandings of other participants is a hallmark of qualitative research. This is the opposite of quantitative research, in which definitions must be completely set in stone before the inquiry can begin.

The contrast between qualitative and quantitative conceptualization is instructive for understanding how quantitative methods (and positivist research in general) privilege the knowledge of the researcher over the knowledge of study participants and community members. Positivism holds that the researcher is the "expert," and can define concepts based on their expert knowledge of the scientific literature. This knowledge is in contrast to the lived experience that participants possess from experiencing the topic under examination day-in, day-out. For this reason, it would be wise to remind ourselves not to take our definitions too seriously and be critical about the limitations of our knowledge.

Conceptualization must be open to revisions, even radical revisions, as scientific knowledge progresses. While I’ve suggested consulting prior scholarly definitions of our concepts, you should not assume that prior, scholarly definitions are more real than the definitions we create. Likewise, we should not think that our own made-up definitions are any more real than any other definition. It would also be wrong to assume that just because definitions exist for some concept that the concept itself exists beyond some abstract idea in our heads. Building on the paradigmatic ideas behind interpretivism and the critical paradigm, researchers call the assumption that our abstract concepts exist in some concrete, tangible way is known as reification. It explores the power dynamics behind how we can create reality by how we define it.

Returning again to our example of masculinity. Think about our how our notions of masculinity have developed over the past few decades, and how different and yet so similar they are to patriarchal definitions throughout history. Conceptual definitions become more or less popular based on the power arrangements inside of social science the broader world. Western knowledge systems are privileged, while others are viewed as unscientific and marginal. The historical domination of social science by white men from WEIRD countries meant that definitions of masculinity were imbued their cultural biases and were designed explicitly and implicitly to preserve their power. This has inspired movements for cognitive justice as we seek to use social science to achieve global development.

Key Takeaways

- Measurement is the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating.

- Kaplan identified three categories of things that social scientists measure including observational terms, indirect observables, and constructs.

- Some concepts have multiple elements or dimensions.

- Researchers often use measures previously developed and studied by other researchers.

- Conceptualization is a process that involves coming up with clear, concise definitions.

- Conceptual definitions are based on the theoretical framework you are using for your study (and the paradigmatic assumptions underlying those theories).

- Whether your conceptual definitions come from your own ideas or the literature, you should be able to situate them in terms of other commonly used conceptual definitions.

- Researchers should acknowledge the limited explanatory power of their definitions for concepts and how oppression can shape what explanations are considered true or scientific.

Exercises

Think historically about the variables in your research question.

- How has our conceptual definition of your topic changed over time?

- What scholars or social forces were responsible for this change?

Take a critical look at your conceptual definitions.

- How participants might define terms for themselves differently, in terms of their daily experience?

- On what cultural assumptions are your conceptual definitions based?

- Are your conceptual definitions applicable across all cultures that will be represented in your sample?

11.3 Inductive and deductive reasoning

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to...

- Describe inductive and deductive reasoning and provide examples of each

- Identify how inductive and deductive reasoning are complementary

Congratulations! You survived the chapter on theories and paradigms. My experience has been that many students have a difficult time thinking about theories and paradigms because they perceive them as "intangible" and thereby hard to connect to social work research. I even had one student who said she got frustrated just reading the word "philosophy."

Rest assured, you do not need to become a theorist or philosopher to be an effective social worker or researcher. However, you should have a good sense of what theory or theories will be relevant to your project, as well as how this theory, along with your working question, fit within the three broad research paradigms we reviewed. If you don't have a good idea about those at this point, it may be a good opportunity to pause and read more about the theories related to your topic area.

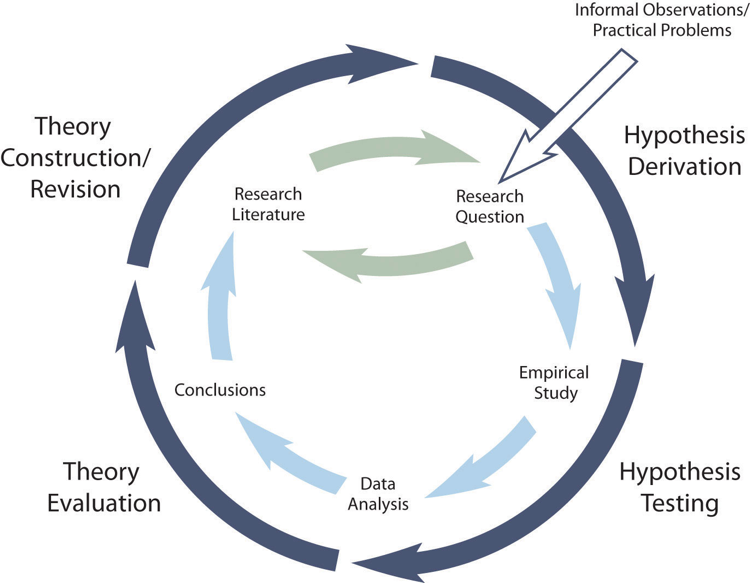

Theories structure and inform social work research. The converse is also true: research can structure and inform theory. The reciprocal relationship between theory and research often becomes evident to students when they consider the relationships between theory and research in inductive and deductive approaches to research. In both cases, theory is crucial. But the relationship between theory and research differs for each approach.

While inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

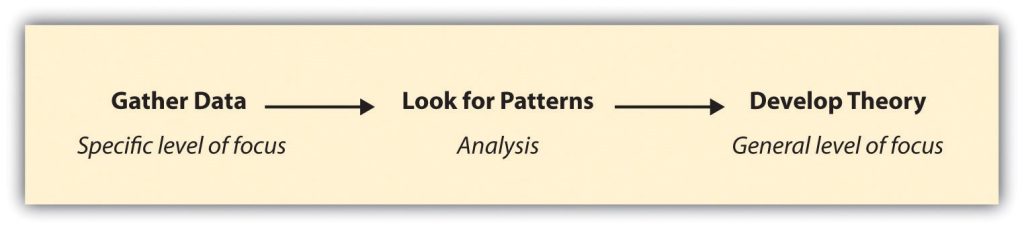

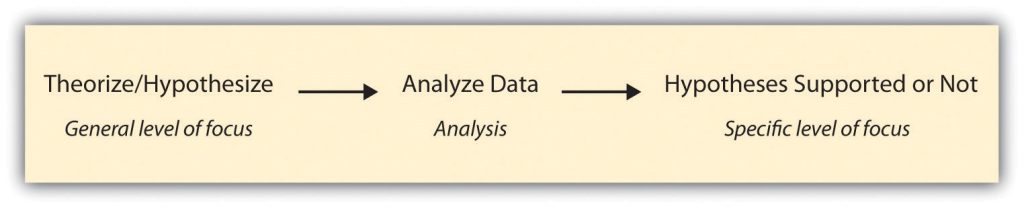

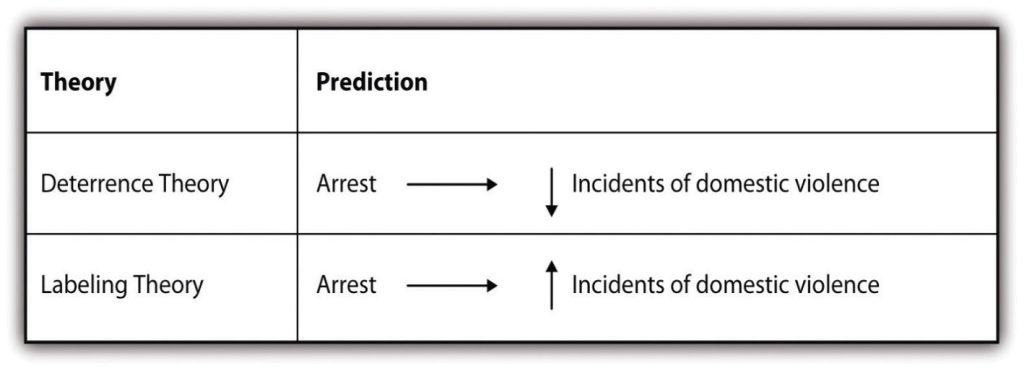

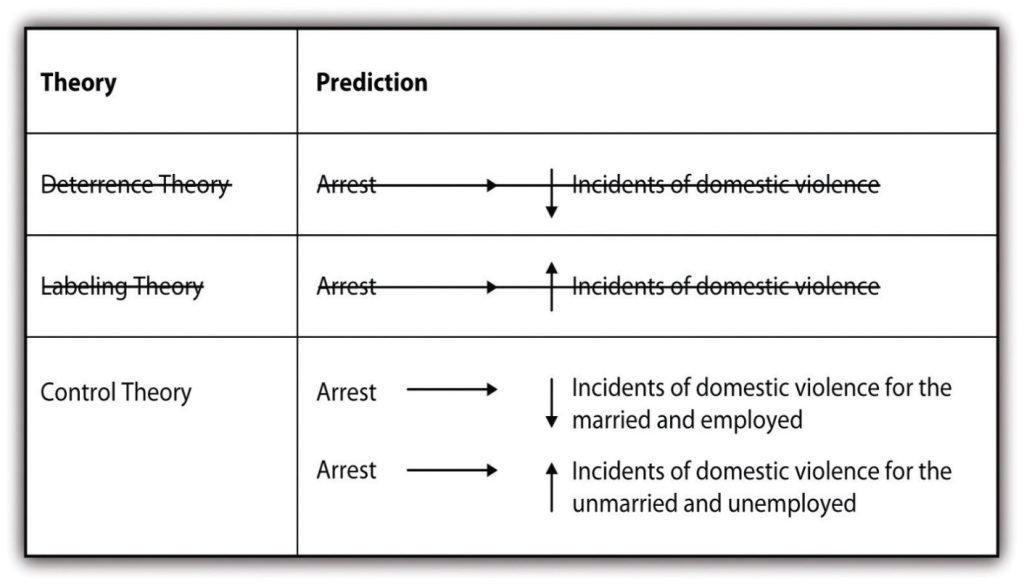

Inductive reasoning