Preface: Social workers’ roles in science and research

Chapter Outline

- Social workers’ roles in science and research (10-minute read)

Social workers’ roles in science and research

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Differentiate between formal and informal research roles

- Describe common barriers to engaging with social work research

Formal and informal research roles

I’ve been teaching research methods for six years and have found that many students struggle to see the connection between research and social work practice. First of all, it’s important to mention that social work researchers exist! The authors of this textbook are social work researchers across university, government, and non-profit institutions. Matt and Cory are researchers at universities, and our research addresses higher education, disability policy, wellness & mental health, and intimate partner violence. Kate is a researcher at the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission in Virginia, where she studies policies related to criminal justice. Dalia, our editor, is a behavioral health researcher at RTI International, a nonprofit research institute, where she studies the opioid epidemic. The career path for social workers in formal research roles is bright and diverse, as we each bring a unique perspective with our ethical and theoretical orientation.

Formal research results in written products like journal articles, government reports, or policy briefs. To get a sense of formal research roles in social work, consider asking a professor about their research. You can also browse around the top journals in social work: Trauma, Violence & Abuse, Child Maltreatment, Child Abuse & Neglect, Social Service Review, Family Relations, Journal of Social Policy, Social Policy & Administration, Research on Social Work Practice, Health & Social Care in the Community, Health & Social Work, British Journal of Social Work, Child & Family Social Work, International Journal of Social Welfare, Qualitative Social Work, Children & Youth Services Review, Social Work, Social Work in Health Care, Journal of Social Work Practice, International Social Work, Affilia Journal of Women and Social Work, and Clinical Social Work Journal. Additionally, the websites to most government agencies, foundations, think tanks, and advocacy groups contain formal research often conducted by social workers.

But let’s be clear, studies show that most social work students are not interested in becoming social work researchers who publish journal articles or research reports (DeCarlo et al., 2019; Earley, 2014).[1] Once you enter post-graduate practice, you will need to apply your formal research skills to the informal research conducted by practitioners and agencies every day. Every time you are asking who, what, when, where and why, you are conducting informal research. Informal research can be more involved. Social workers may be surprised when they are asked to engage in research projects such as needs assessments, community scans, program and policy evaluations, and single system designs, to name a few. Macro-oriented students may have to conduct research on programs and policies as part of advocacy or administration. We cannot tell you the number former students who have contacted us looking for research resources or wanting to “pick our brains” about research they are doing as part of their employment.

Research for action

Regardless of whether a social worker conducts formal research that results in journal articles or informal research that is used within an agency, all social work research is distinctive in that it is active (Engel & Schutt, 2016).[2] We want our results to be used to effect social change. Sometimes this means using findings to change how clients receive services. Sometimes it means using findings to show the benefits of programs or policies. Sometimes it means using findings to speak with those oppressed and marginalized persons who have been left out of the policy creation process. Additionally, it can mean using research as the mode with which to engage a constituency to address a social justice issue. All of these research activities differ; however, the one consistent ingredient is that these activities move us towards social and economic justice.

Student anxieties and beliefs about research

Unfortunately, students generally arrive in research methods classes with a mixture of dread, fear, and frustration. If you attend any given social work education conference, there is probably a presentation on how to better engage students in research. There is an entire body of academic research that verifies what any research professor knows to be true. Honestly, this is why the authors of this textbook started this project. We want to make research more enjoyable and engaging for students. Generally, we have found some common perceptions get in the way of students (at least) minimally enjoying research. Let’s see if any of these match with what you are thinking.

I’m never going to use this crap!

Students who tell us that research methods is not useful to them are saying something important. As a student scholar, your most valuable asset is your time. You give your time to the subjects you consider important to you and for your career. Because most social workers don’t become researchers or practitioner-researchers, students may feel that a research methods class is a waste of time. As faculty members, we often hear from supervisors of students in field placements that research competencies “do not apply in this setting,” which further reinforces the idea that research is an activity performed only by academic researchers.

Our discussion of evidence-based practice and the ways in which social workers use research in practice brought home the idea that social workers play an important role in creating and disseminating new knowledge about social services. Furthermore, in the coming chapters, we will explore the role of research as a human right that is closely associated with the protection and establishment of other human rights. A human rights perspective also highlights the structural barriers students and practitioners face in accessing and applying scholarly knowledge in the practice arena. We hope that reframing research as something ordinary and easy to do will help address this belief that research is a useless skill.

One thing we can guarantee is that this class will be immediately useful to you. In particular, the skills you develop in finding, evaluating, and using scholarly literature will serve you throughout your graduate program and throughout your lifelong learning. In this book, you will learn how to understand and apply the scientific method to whatever topic interests you.

Research is only for super-smart people

Research methods involves a lot of terminology that may be entirely new to social work students. Other domains of social work, such as practice, are easier to apply your intuition towards. You understand how to be an empathetic person, and your experiences in life can help guide you through a practice situation or even a theoretical or conceptual question. Research may seem like a totally new area in which you have no previous experience. In research methods there can be “wrong” answers. Depending on your research question, some approaches to data analysis or measurement, for example, may not help you find the correct answer.

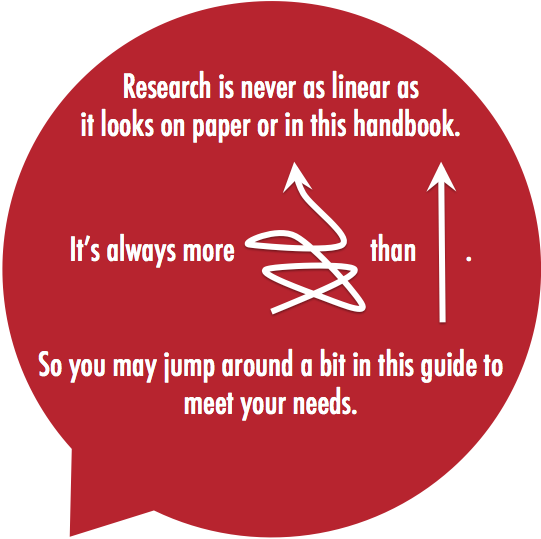

The fear is entirely understandable. Research is not straightforward. As Figure 1.1 shows, it is a process that is non-linear, involving multiple revisions, wrong turns, and dead ends before you figure out the best question and research approach. You may have to go back to chapters after having read them or even peek ahead at chapters your class hasn’t covered yet.

Moreover, research is something you learn by doing…and stumbling a few times. It’s an iterative process, or one that requires many tries to get right. There isn’t a shortcut for learning research, but if you follow along with the exercises in this book, you can break down a student research project and accomplish it piece by piece. No one just knows research. It’s something you pick up by doing it, reflecting on the experiences and results, redoing your work, and revising it in consultation with your professor and peers. Research involves exploration, risk taking, and a willingness to say, “Let’s see what we will find!”

Research is designed to suck the joy from my life

We’ve talked already about the arcane research terminology, so we won’t go into it again here. But students sometimes perceive research methods as boring. Practice knowledge and even theory are fun to learn because they are easy to apply and provide insights into the world around you. Research just seems like its own weirdly shaped and ill-fitting puzzle piece.

We completely understand where this perspective comes from and hope there are a few things you will take away from this course that aren’t boring to you. In the first section of this textbook, you will learn how to take any topic and learn what is known about it. It may seem trivial, but this is actually a superpower. Your social work education will teach you basic knowledge that can be applied to nearly all social work practice situations as well as some applied material applicable to specific social work practice situations. However, no education will provide you with everything you need to know. And certainly, no professor can tell you what will be discovered over the next few decades of your practice. Our work on literature reviews in the next few chapters will help you increase your skills and knowledge to become a strong social work student and practitioner. Following that, our exploration of research methods will help you understand how theories, practice models, and techniques you learn in other classes are created and tested scientifically. Eventually, you’ll see how all of the pieces fit together.

Get out of your own way

Together, these misconceptions and myths can create a self-fulfilling prophecy for students. If you believe research is boring, you won’t find it interesting. If you believe research is hard, you will struggle more with assignments. If you believe research is useless, you won’t see its utility. If you’re afraid that you will make mistakes, then you won’t want to try. While we certainly acknowledge that students aren’t going to love research as much as we do (we spent over a year writing this book, so we like it a lot!), we suggest reframing how you think about research using the following touchstones:

- All social workers rely on social science research to engage in competent practice.

- No one already knows research. It’s something I’ll learn through practice. And it’s challenging for everyone, not just me.

- Research is relevant to me because it allows me to figure out what is known about any topic I want to study.

- If the topic I choose to study is important to me, I will be more interested in exploring research to help me understand it further.

Students should be intentional about managing any anxiety coming from a research project. Here are some suggestions:

- Talk to your professor if you are feeling lost. We like students!

- Talk to a librarian if you are having trouble finding information about your topic.

- Seek support from your peers or mentors.

Another way to reframe your thinking is to look at the final chapter, which discusses how to share your research project with the world. Consider the impact you want to make with your project, who you want to share it with, and what it will mean to have answered a question you want to know about the social world. Look at the variety of professional and academic conferences in which social work practitioners and researchers share their knowledge. Think about where you want to go so you know how to get started.

The structure of this textbook

The textbook is divided into four parts. Part 1 reviews the two research roles you will use most in social work education–consuming scientific information and communicating about it. We will walk you through conceptualizing a working question, reading literature, and writing a literature review. Next, we will take that literature review and propose a potential research project to expand scientific knowledge. This is the third research role social workers take on: creating scientific information. Parts 2 and 3 of the textbook review quantitative and qualitative methods researchers can use to establish scientific truths to research questions. Whether performing formal or information research roles, social workers consume, communicate, and create scientific information for social change.

In the first part (Chapters 1-6), we will review how to orient your research proposal to a specific question you want to answer and review the literature to see what we know about it.

In the second part (Chapters 7-14), we will introduce how to use quantitative research methods like surveys and experiments, construct questionnaires, and assess their accuracy for diverse groups.

In the third part (Chapters 15-19) we will introduce how to use qualitative research methods like interviews and focus groups, assess trustworthiness and authenticity of results, and choose between different qualitative research designs.

In the fourth part (Chapter 20-25) we will discuss how social workers analyze research data and share it with stakeholders.

If you are still figuring out how to navigate the book using your internet browser, please go to the Downloads and Resources for Students page which contains a number of quick video tutorials. Also, the exercises in each chapter allow you to apply what you wrote to your own research project, and the textbook is designed so that each exercise and each chapter build on one another, completing your proposal step-by-step. Of course, some exercises may be more relevant than others, but please consider completing these as you read.

Key Takeaways

- Social workers engage in formal and informal research production as part of practice.

- If you feel anxious, bored, or overwhelmed by research, you are not alone!

- Becoming more familiar with research methods will help you become a better scholar and social work practitioner.

Exercises

- With your peers, explore your feelings towards your research methods classes. Describe some themes that come up during your conversations. Identify which issues can be addressed by your professor and which can be addressed by students.

- Browse social work journals and identify an article of interest to you. Look up the author’s biography or curriculum vitae on their personal website or the website of their university.

- DeCarlo, M. P., Schoppelrey, S., Crenshaw, C., Secret, M. C., & Stewart, M. (2020, January 1). Open educational resources and graduate social work students: Cost, outcomes, use, and perceptions. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/k4ytd; Earley, M. A. (2014). A synthesis of the literature on research methods education. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), 242-253. ↵

- Engel, R. J. & Schutt, R. K. (2016) The practice of research in social work (4th edition). Washington, DC: Sage Publications ↵