18.2 Financial Planning

[Author removed at request of original publisher], Published by University of Minnesota

Before we go any further, we need to nail down a couple of key concepts. First, just what, exactly, do we mean by personal finances? Finance itself concerns the flow of money from one place to another, and your personal finances concern your money and what you plan to do with it as it flows in and out of your possession. Essentially, then, personal finance is the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make either for your individual benefit or for that of your family.

Second, as we suggested in “Where Does Your Money Go?”—and as we’ll insist in the rest of this chapter—monetary decisions work out much more beneficially when they’re planned rather than improvised. Thus our emphasis on financial planning—the ongoing process of managing your personal finances in order to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

Financial planning requires you to address several questions, some of them relatively simple:

- What’s my annual income?

- How much debt do I have, and what are my monthly payments on that debt?

Others will require some investigation and calculation:

- What’s the value of my assets?

- How can I best budget my annual income?

Still others will require some forethought and forecasting:

- How much wealth can I expect to accumulate during my working lifetime?

- How much money will I need when I retire?

The Financial Planning Life Cycle

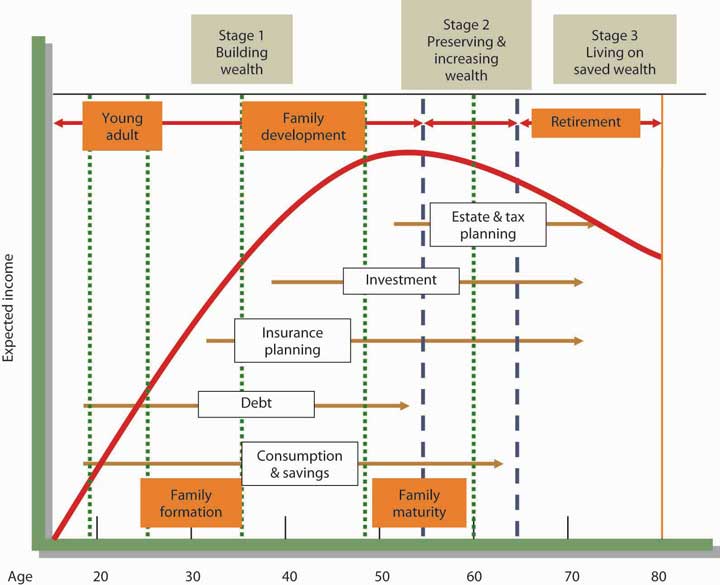

Another question that you might ask yourself—and certainly would do if you were a professional in financial planning—is something like, “How will my financial plans change over the course of my life?” Figure 18.4: Financial Life Cycle illustrates the financial life cycle of a typical individual—one whose financial outlook and likely outcomes are probably a lot like yours (Keown, 2007). As you can see, our diagram divides this individual’s life into three stages, each of which is characterized by different life events (such as beginning a family, buying a home, planning an estate, retiring). At each stage, too, there are recommended changes in the focus of the individual’s financial planning:

- In stage 1, the focus is on building wealth.

- In stage 2, the focus shifts to the process of preserving and increasing the wealth that one has accumulated and continues to accumulate.

- In stage 3, the focus turns to the process of living on (and, if possible, continuing to grow) one’s saved wealth.

At each stage, of course, complications can set in—say, changes in such conditions as marital or employment status or in the overall economic outlook. Finally, as you can also see, your financial needs will probably peak somewhere in stage 2, at approximately age fifty-five, or ten years before typical retirement age.

Choosing a Career

Until you’re eighteen or so, you probably won’t generate much income; for the most part, you’ll be living off your parents’ wealth. In our hypothetical life cycle, however, financial planning begins in the individual’s early twenties. If that seems like rushing things, consider a basic fact of life: this is the age at which you’ll be choosing your career—not only the sort of work you want to do during your prime income-generating years, but also the kind of lifestyle you want to live in the process (Keown, 2007).

What about college? Most readers of this book, of course, have decided to go to college. If you haven’t yet decided, you need to know that college is an extremely good investment of both money and time.

Table 18.1: Education and Average Income, for example, summarizes the findings of a study conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). A quick review shows that people who graduate from high school can expect to increase their average annual earnings by about 49 percent over those of people who don’t, and those who go on to finish college can expect to generate 82 percent more annual income than that. Over the course of the financial life cycle, families headed by those college graduates will earn about $1.6 million more than families headed by high school graduates who didn’t attend college. (With better access to health care—and, studies show, with better dietary and health practices—college graduates will also live longer. And so will their children.) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008)

| Education | Average income | Percentage increase over next-highest level |

|---|---|---|

| High school dropout | $20,873 | — |

| High school diploma | $31,071 | 48.9% |

| College degree | $56,788 | 82.8% |

| Advanced higher-education degree | $82,320 | 45.0% |

And what about the debt that so many people accumulate to finish college? For every $1 that you spend on your college education, you can expect to earn about $35 during the course of your financial life cycle (Hansen, 2008). At that rate of return, you should be able to pay off your student loans (unless, of course, you fail to practice reasonable financial planning).

Naturally, there are exceptions to these average outcomes. You’ll find English-lit majors stocking shelves at 7-Eleven, and you’ll find college dropouts running multibillion-dollar enterprises. Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates dropped out of college after two years, as did his founding partner, Paul Allen. Current Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer finished his undergraduate degree but quit his MBA program to join Microsoft (where he apparently fit in among the other dropouts in top management). It’s always good to remember, however, that though exceptions to rules (and average outcomes) occasionally modify the rules, they invariably fall far short of disproving them: in entrepreneurship as in most other walks of adult life, the better your education, the more promising your financial future. One expert in the field puts the case for the average person bluntly: educational credentials “are about being employable, becoming a legitimate candidate for a job with a future. They are about climbing out of the dead-end job market” (Ramsay, 2008).

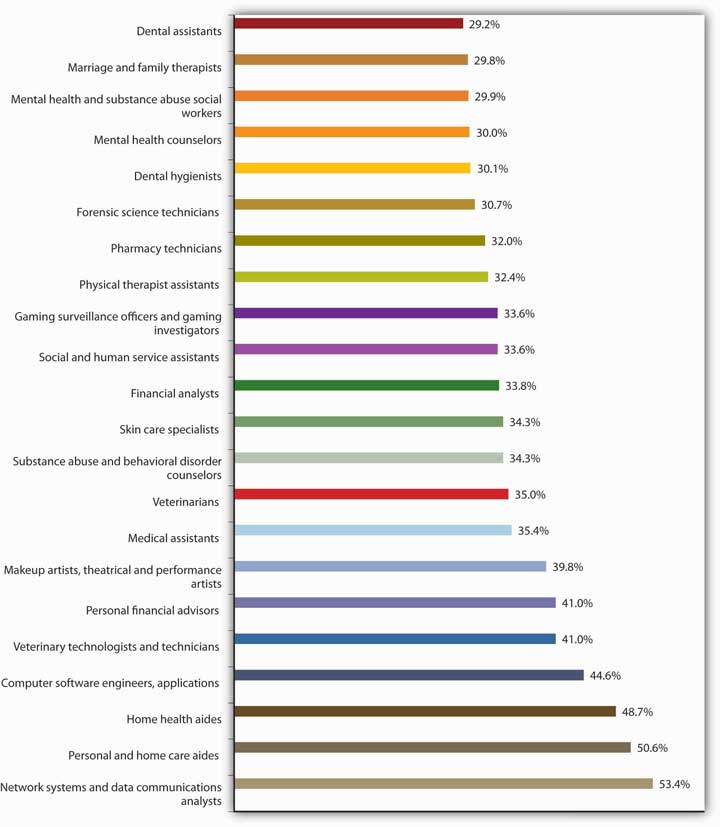

Finally, does it make any difference what you study in college? To a perhaps surprising extent, not necessarily. Some career areas, such as engineering, architecture, teaching, and law, require targeted degrees, but the area of study designated on your degree often doesn’t matter much when you’re applying for a job. If, for instance, a job ad says, “Business, communications, or other degree required,” most applicants and hires will have those “other” degrees. When poring over résumés for a lot of jobs, potential employers look for the degree and simply note that a candidate has one; they often don’t need to focus on the particulars (Roth, 2008).Figure 18.5 “Top 25 Fastest-Growing Jobs, 2006–2016”, for example, summarizes a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projection of the thirty fast-growing occupations for the years 2006–2016. Veterinary technicians and makeup artists will be in demand as never before, but as you can see, occupational prospects are fairly diverse1.

Nor, of course, do all degrees pay off equally. In Table 18.2: College Majors and Average Annual Earnings, we’ve extracted the findings of a study conducted by the National Science Foundation on the earnings of individuals with degrees in various undergraduate fields (Penrice, 1999; Harrington & Sum, 2011). Clearly, some degrees—notably in the engineering fields—promise much higher average earnings than others. Chemical engineers, for instance, can earn nearly twice as much as elementary school teachers, but there’s a catch: if you graduate with a degree in chemical engineering, your average annual salary will be about $67,000 if you can find a job related to that degree; if you can’t, you may have to settle for as much as 40 percent less (Penrice, 1999). (Supermodel Cindy Crawford cut short her studies in chemical engineering because there was more money to be made on the runway.)

| Major | Average Earnings with Bachelor’s Degree | Major | Average Earnings with Bachelor’s Degree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical engineering | $67,425 | History | $45,926 |

| Aerospace engineering | $65,649 | Biology | $45,532 |

| Computer engineering | $62,527 | Nursing | $45,538 |

| Physics | $62,104 | Psychology | $43,963 |

| Electrical engineering | $61,534 | English | $43,614 |

| Mechanical engineering | $61,382 | Health technology | $42,524 |

| Industrial engineering | $61,030 | Criminal justice | $41,129 |

| Civil engineering | $58,993 | Physical education | $40,207 |

| Accounting | $56,637 | Secondary education | $39,976 |

| Finance | $55,104 | Fine arts | $38,857 |

| Computer science | $52,615 | Philosophy | $38,239 |

| Business management | $52,321 | Dramatic arts | $37,091 |

| Marketing | $51,107 | Music | $36,811 |

| Journalism | $46,835 | Elementary education | $34,564 |

| Information systems | $46,519 | Special education | $34,196 |

In short, when you’re planning what to do with the rest of your life, it’s a good idea to check into the fine points and realities, as well as the statistical data. If you talk to career counselors and people in the workforce, you might be surprised by what you learn about the relationship between certain college majors and various occupations. Onetime Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina majored in medieval history and philosophy.

Financing a College Education

Let’s revisit one of the facts included in the earlier discussion: for every $1 that you spend on your college education, you can expect to earn about $35 during the course of your financial life cycle. And let’s say you’re convinced (as you should be) that getting a college degree is a wise financial choice. You still have to deal with the cost of getting your degree. We’re sure this won’t come as a surprise: attending college is expensive—tuition and fees have gone up sharply, the cost of books has skyrocketed, and living expenses have climbed. Many students can attend college only if they receive some type of financial aid. Though the best way to learn what aid is available to you is to talk with a representative in the financial aid office at your school, this section provides an overview of the types of aid offered to students. Students finance their education through scholarships, grants, education loans, and work-study programs (Witmer, 2011). We’ll explore each of these categories of aid:

- Scholarships, which don’t have to be repaid, are awarded based on a number of criteria, including academic achievement, athletic or artistic talent, special interest in a particular field of study, ethnic background, or religious affiliation. Scholarships are generally funded by private donors such as alums, religious institutions, companies, civic organizations, professional associations, and foundations.

- Grants, which also don’t have to be repaid, are awarded based on financial need. They’re funded by the federal government, the states, and academic institutions. An example of a common federal grant is the Pell Grant, which is awarded to undergraduate students based on financial need. The maximum Pell Grant award for the 2011–12 award year (July 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012) is $5,550 (Federal Student Aid, 2011).

- Education loans, which must be repaid, are available to students from various sources, including the federal government, states, and academic institutions. While recent problems in the credit markets have made college loans more difficult to obtain, most students are able to get the loans they need (Snyder, 2008). The loans offered directly to undergraduate students by the federal government include the need-based, subsidized Federal Stafford, the non–need-based unsubsidized Federal Stafford, and the need-based Federal Perkins loans. With the exception of the unsubsidized Federal Stafford, no interest accrues while the student is enrolled in college at least part time. There are also a number of loans available to parents of students, such as the Federal Parent PLUS program. Under this program, parents can borrow federally guaranteed low-interest loans to fund their child’s education.

- Work-study is a federally sponsored program that provides students with paid, part-time jobs on campus. Because the student is paid based on work done, the funds received don’t have to be repaid.

Find a Great Job

As was highlighted earlier, your financial life cycle begins at the point when you choose a career. Building your career takes considerable planning. It begins with the selection of a major in college and continues through graduation as you enter the workforce full time. You can expect to hold a number of jobs over your working life. If things go as they should, each job will provide valuable opportunities and help you advance your career. A big challenge is getting a job offer in your field of interest, evaluating the offer, and (if you have several options) selecting the job that’s right for you2.

Getting a Job Offer

Most likely your college has a career center. The people working there can be a tremendous help to you as you begin your job search. But most of the work has to be done by you. Like other worthwhile projects, your job search project will be very time-consuming. As you get close to graduation, you’ll need to block out time to work on this particularly important task.

The first step is to prepare a résumé, a document that provides a summary of educational achievements and relevant job experience. Its purpose is to get you an interview. A potential employer will likely spend less than a minute reviewing your résumé, so its content should be concise, clear, and applicable to the job for which you’re applying. For some positions, the person in charge of hiring might read more than a hundred résumés. If you don’t want your résumé kicked out right away, be sure it contains no typographical or grammatical errors. Once you’ve completed your résumé, you can use it to create different versions tailored to specific companies you’d like to work for. Your next step is to write a cover letter, a document accompanying your résumé that explains why you’re sending your résumé and highlights your qualifications. You can find numerous tips on writing résumés and cover letters (as well as samples of both) online. Be sure your résumé is accurate: never lie or exaggerate in a résumé. You could get caught and not get the job (or—even worse—you could get the job, get caught, and then get fired). It’s fairly common practice for companies to conduct background checks of possible employees, and these checks will point out any errors. In effect, says one expert, “you jeopardize your future when you lie about your past” (Isaacs, 2011).

After writing your résumé and cover letter, your next task is to create a list of companies you’d like to work for. Use a variety of sources, including your career services office and company Web sites, to decide which companies to put on your list. Visit the “career or employment” section of the company Web sites and search for specific openings.

You could also conduct a general search for positions that might be of interest to you, by doing the following:

- Visiting career Web sites, such as Monster.com or Careerbuilder.com (which maintain large databases of openings for all geographical areas)

- Searching classified ads in online and print newspapers

- Attending career fairs at your college and in your community

- Signing up with career services to talk with recruiters when they visit your campus

- Contacting your friends, family, and college alumni and letting them know you’re looking for a job and asking for their help

Once you spot a position you want, send your résumé and cover letter (tailored to the specific company and job). Follow up in a few days to be sure your materials got to the right place, and offer to provide any additional information. Keep notes on all contacts.

When you’re invited for an interview, visit to the company’s Web site and learn as much as you can about the company. Practice answering questions you might be asked during the interview, and think up a few pertinent questions to ask your interviewer. Dress conservatively—males should wear a suit and tie and females should wear professional-looking clothes. Try to relax during the interview (though everyone knows this isn’t always easy). Your goal is to get an offer, so let the interviewer learn who you are and how you can be an asset to the company. Send a thank-you note (or thank-you e-mail) to the interviewer after the interview.

Evaluating Job Offers

Let’s be optimistic and say that you did quite well in your interviews, and you have two job offers. It’s a great problem to have, but now you have to decide which one to accept. Salary is important, but it’s clearly not the only factor. You should consider the opportunities the position offers: will you learn new things on the job, how much training will you get, could you move up in the organization (and if so, how quickly)? Also consider quality of life issues: how many hours a week will you have to work, is your schedule predictable (or will you be asked to work on a Friday night or Saturday at the last minute), how flexible is your schedule, how much time do you get off, how stressful will the job be, do you like the person who will be your manager, do you like your coworkers, how secure is the job, how much travel is involved, where’s the company located, and what’s the cost of living in that area? Finally, consider the financial benefits you’ll receive. These could include health insurance, disability insurance, flexible spending accounts, and retirement plans. Let’s talk more about the financial benefits, beginning with health insurance.

- Employer-sponsored health insurance plans vary greatly. Some cover the employee only, while others cover the employee, spouse, and children. Some include dental and eye coverage while others don’t. Most plans require employees to share some of the cost of the medical plan (by paying a portion of the insurance premiums and a portion of the cost of medical care). But the amount that employees are responsible for varies greatly. Given the rising cost of health insurance, it’s important to understand the specific costs associated with a health care plan and to take these costs into account when comparing job offers. More important, it’s vital that you have medical insurance. Young people are often tempted to go without medical insurance, but this is a major mistake. An uncovered, costly medical emergency (say you’re rushed to the hospital with appendicitis) can be a financial disaster. You could end up paying for your hospital and doctor care for years.

- Disability insurance isn’t as well known as medical insurance, but it can be as important (if not more so). Disability insurance pays an income to an insured person when he or she is unable to work for an extended period. You would hope that you’d never need disability insurance, but if you did it would be of tremendous value.

- A flexible spending account allows a specified amount of pretax dollars to be used to pay for qualified expenses, including health care and child care. By paying for these costs with pretax dollars, employees are able to reduce their tax bill.

- There are two main types of retirement plans. One, called a defined benefit retirement plan, provides a set amount of money each month to retirees based on the number of years they worked and the income they earned. This form of retirement plan was once very popular, but it’s less common today. The other, called a defined contribution retirement plan, is a form of savings plan. The employee contributes money each pay period to his or her retirement account, and the employer matches a portion of the contribution. Even when retirement is exceedingly far into the future, it’s financially wise to set aside funds for retirement.

Key Takeaways

- Finance concerns the flow of money from one place to another; your personal finances concern your money and what you plan to do with it as it flows in and out of your possession. Personal finance is thus the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make, either for your individual benefit or for that of your family.

- Financial planning is the ongoing process of managing your personal finances to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

-

The financial life cycle divides an individual’s life into three stages, each of which is characterized by different life events. Each stage also entails recommended changes in the focus of the individual’s financial planning:

- In stage 1, the focus is on building wealth.

- In stage 2, the focus shifts to the process of preserving and increasing the wealth that one has accumulated and continues to accumulate.

- In stage 3, the focus turns to the process of living on (and, if possible, continuing to grow) one’s saved wealth.

- According to the model of the financial life cycle, financial planning begins in the individual’s early twenties, the age at which most people choose a career—both the sort of work they want to do during their income-generating years and the kind of lifestyle they want to live in the process.

- College is a good investment of both money and time. People who graduate from high school can expect to improve their average annual earnings by about 49 percent over those of people who don’t, and those who go on to finish college can expect to generate 82 percent more annual income than that. The area of study designated on your degree often doesn’t matter when you’re applying for a job: when poring over résumés, employers often look for the degree and simply note that a candidate has one.

- The first step in your job search is to prepare a résumé, a document that provides a summary of educational achievements and relevant job experience. Your résumé should be concise, clear, applicable to the job for which you are applying, and free of errors and inaccuracies.

- A cover letter is a document that accompanies your résumé and explains why you’re sending your résumé and highlights your qualifications.

-

To conduct a general search for positions that might be of interest to you, you could:

- Visit career Web sites, such as Monster.com, Wetfeet.com, or Careerbuilder.com.

- Search classified ads in online and print newspapers.

- Attend career fairs at your college and in your community.

- Talk with recruiters when they visit your campus.

- Contact people you know, tell them you’re looking for a job, and ask for their help.

- When you’re invited for an interview, you should research the company, practice answering questions you might be asked in the interview, and think up pertinent questions to ask the interviewer.

-

When comparing job offers, consider more than salary. Also of importance are quality of life issues and benefits. Common financial benefits include health insurance, disability insurance, flexible spending accounts, and retirement plans.

- Employer-sponsored health insurance plans vary greatly in coverage and cost to the employee.

- Disability insurance pays an income to an insured person when he or she is unable to work for an extended period of time.

- A flexible spending account allows a specified amount of pretax dollars to be used to pay for qualified expenses, including health care and child care. By paying for these costs with pretax dollars, employees are able to reduce their tax bill.

- There are two main types of retirement plans: a defined benefit plan, which provides a set amount of money each month to retirees based on the number of years they worked and the income they earned, and a defined contribution plan, which is a form of savings plan into which both the employee and employer contribute. A well-known defined contribution plan is a 401(k).

Exercise

Think of the type of job you’d like to have. Describe the job and indicate how you’d go about getting a job offer for this type of job. How would you evaluate competing offers from two companies? What criteria would you use in selecting the right job for you?

1http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/print.pl/news.release/ecopro.t06.htm (November 11, 2011).

2This section is based in part on sections 13 and 14 of the Playbook for Life by The Hartford. The Playbook can be found on line at http://www.playbook.thehartford.com (accessed November 11, 2011).

References

Federal Student Aid, “Federal Pell Grant,” http://studentaid.ed.gov/PORTALSWebApp/students/english/PellGrants.jsp?tab=funding (accessed November 11, 2011).

Hansen, K., “What Good Is a College Education Anyway?” Quintessential Careers (2008), http://www.quintcareers.com/college_education_value.html (accessed November 11, 2011).

Harrington, P., and Andrew Sum, “The Post-College Earnings Experiences of Bachelor Degree Holders in the U.S.: Estimated Economic Returns to Major Fields of Study,” in Learning and Work on Campus and on the Job: The Evolving Relationship between Higher Education and Employment, ed. S. Reder, B. A. Holland, and M. P. Latiolais (in preparation).

Isaacs, K., “Lying on Your Resume: What Are the Career Consequences?,” Monster.com, http://insidetech.monster.com/careers/articles/3574-lying-on-your-resume-what-are-the-career-consequences (accessed November 11, 2011).

Keown, A. J., Personal Finance: Turning Money into Wealth, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2007), 8–11.

Penrice, D., “Major Moolah: Adding Up the Earnings Gaps in College Majors,” N.U. Magazine, January 1999, http://www.northeastern.edu/magazine/9901/labor.html (accessed November 11, 2011).

Ramsay, J. G., Perlman Center for Learning and Teaching, quoted by Katharine Hansen, “What Good Is a College Education Anyway?” Quintessential Careers (2008), http://www.quintcareers.com/college_education_value.html (accessed November 11, 2011).

Roth, J. D., “The Value of a College Education,” Get Rich Slowly, January 10, 2008, http://www.getrichslowly.org/blog/2008/01/10/the-value-of-a-college-education/ (accessed November 11, 2011).

Snyder, S., “College lending tight but available,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, August 18, 2008, http://www.philly.com/inquirer/education/20080818_College_lending_tight_but_available.html (accessed November 11, 2011).

U.S. Census Bureau, “One-Third of Young Women Have Bachelor’s Degrees” (U.S. Department of Commerce, January 10, 2008), http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/education/011196.html (accessed September 18, 2008).

Witmer, D., “The Basics of Financial Aid for College,” About.com, http://parentingteens.about.com/od/collegeinfo/a/financial_aid.htm (accessed November 11, 2011).

The ongoing process of managing your personal finances in order to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

a document that provides a summary of educational achievements and relevant job experience

a document accompanying your résumé that explains why you’re sending your résumé and highlights your qualifications

pays an income to an insured person when he or she is unable to work for an extended period

allows a specified amount of pretax dollars to be used to pay for qualified expenses, including health care and child care

provides a set amount of money each month to retirees based on the number of years they worked and the income they earned

The employee contributes money each pay period to his or her retirement account, and the employer matches a portion of the contribution