3.4 Identifying Ethical Issues

[Author removed at request of original publisher], Published by University of Minnesota

Make no mistake about it: When you enter the business world, you’ll find yourself in situations in which you’ll have to choose the appropriate behavior. How, for example, would you answer questions like the following?

- Is it OK to accept a pair of sports tickets from a supplier?

- Can I buy office supplies from my brother-in-law?

- Is it appropriate to donate company funds to my local community center?

- If I find out that a friend is about to be fired, can I warn her?

- Will I have to lie about the quality of the goods I’m selling?

- Can I take personal e-mails and phone calls at work?

- What do I do if I discover that a coworker is committing fraud?

Obviously, the types of situations are numerous and varied. Fortunately, we can break them down into a few basic categories: bribes, conflicts of interest, conflicts of loyalty, issues of honesty and integrity, and whistle-blowing. Let’s look a little more closely at each of these categories.

Issues of Honesty and Integrity

Master investor Warren Buffet once told a group of business students the following: “I cannot tell you that honesty is the best policy. I can’t tell you that if you behave with perfect honesty and integrity somebody somewhere won’t behave the other way and make more money. But honesty is a good policy. You’ll do fine, you’ll sleep well at night and you’ll feel good about the example you are setting for your coworkers and the other people who care about you.”[35]

If you work for a company that settles for its employees’ merely obeying the law and following a few internal regulations, you might think about moving on. If you’re being asked to deceive customers about the quality or value of your product, you’re in an ethically unhealthy environment.

Think About This Story:

“A chef put two frogs in a pot of warm soup water. The first frog smelled the onions, recognized the danger, and immediately jumped out. The second frog hesitated: The water felt good and he decided to stay and relax for a minute. After all, he could always jump out when things got too hot. As the water got hotter, however, the frog adapted to it, hardly noticing the change. Before long he was the main ingredient in frog-leg soup.”[36]

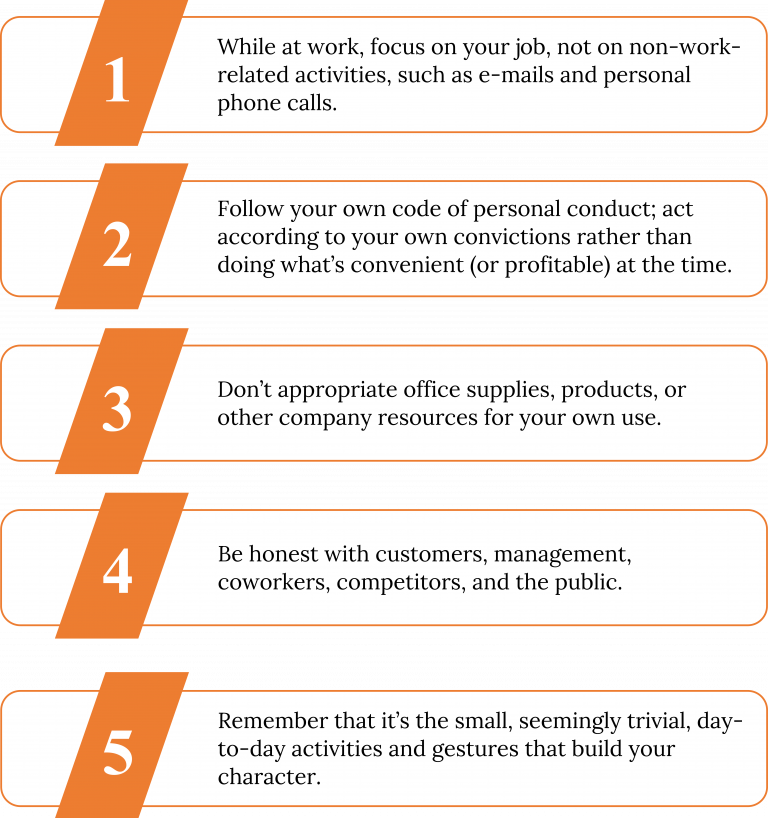

So, what’s the moral of the story? Don’t sit around in an ethically compromised environment and lose your integrity a little at a time; get out before the water gets too hot and your options have evaporated. Fortunately, a few rules of thumb can guide you. We’ve summed them up in figure 4.5.

Figure 4.5: How to maintain honesty and integrity.

Time and Pressure

The frog example reminds us that decision making while under pressure can be pretty important. Unfortunately, we will often be short on time when we are facing some decisions. This is why it is so important to arm ourselves with good ethical models and to know the value of good ethical decision making. If we can practice this decision making in the classroom or in situations when we are not under pressure or out of time, we can be more equipped for those times when time is not available. A common example is practicing a play in sports. In practice a team may walk through the ideal steps in slow motion and do it over and over, so they will be more prepared for the same play or sequence of events during the game when time is not a luxury.

The realities of time and pressure are so important and are another reason why we practice making deadlines in our coursework. We need to manage time well and be aware of when we procrastinate. In many ways procrastination can be thought of as a lid on that heated pot, creating more pressure, and potential disaster. Unfortunately, procrastination is not the only way we can contribute to a potentially unethical environment. We will review some additional challenges in the sections to follow.

Bribes versus Gifts

It’s not uncommon in business to give and receive small gifts of appreciation. But when is a gift unacceptable? When is it really a bribe? If it’s OK to give a bottle of wine to a corporate client during the holidays, is it OK to give a case of wine? If your company is trying to get a big contract, is it appropriate to send a gift to the key decision maker? If it’s all right to invite a business acquaintance to dinner or to a ball game, is it also all right to offer the same person a fully paid weekend getaway?

There’s often a fine line between a gift and a bribe. The questions that we’ve just asked, however, may help in drawing it, because they raise key issues in determining how a gesture should be interpreted: the cost of the item, the timing of the gift, the type of gift, and the connection between the giver and the receiver. If you’re on the receiving end, it’s a good idea to refuse any item that’s overly generous or given for the purpose of influencing a decision. But because accepting even small gifts may violate company rules, the best advice is to check on company policy.

JCPenney’s “Statement of Business Ethics,” for instance, states that employees can’t accept any cash gifts or any noncash gifts except those that have a value below $50 and that are generally used by the giver for promotional purposes. Employees can attend paid-for business functions, but other forms of entertainment, such as sports events and golf outings, can be accepted only if it’s practical for the Penney’s employee to reciprocate. Trips of several days can’t be accepted under any circumstances (JCPenney Co., 2006).

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest occur when individuals must choose between taking actions that promote their personal interests over the interests of others or taking actions that don’t. A conflict can exist, for example, when an employee’s own interests interfere with, or have the potential to interfere with, the best interests of the company’s stakeholders (management, customers, owners). Let’s say that you work for a company with a contract to cater events at your college and that your uncle owns a local bakery. Obviously, this situation could create a conflict of interest (or at least give the appearance of one—which, by the way, is a problem in itself). When you’re called on to furnish desserts for a luncheon, you might be tempted to throw some business your uncle’s way even if it’s not in the best interest of the catering company that you work for.

What should you do? You should probably disclose the connection to your boss, who can then arrange things so that your personal interests don’t conflict with the company’s. You may, for example, agree that if you’re assigned to order products like those that your uncle makes, you’re obligated to find another supplier. Or your boss may make sure that someone else orders bakery products.

The same principle holds that an employee shouldn’t use private information about an employer for personal financial benefit. Say that you learn from a coworker at your pharmaceutical company that one of its most profitable drugs will be pulled off the market because of dangerous side effects. The recall will severely hurt the company’s financial performance and cause its stock price to plummet. Before the news becomes public, you sell all the stock you own in the company. What you’ve done isn’t merely unethical: It’s called insider trading, it’s illegal, and you could go to jail for it.

Conflicts of Loyalty

Sometimes you find yourself in a bind between being loyal either to your employer or to a friend or family member. Perhaps you just learned that a coworker, a friend of yours, is about to be downsized out of his job. You also happen to know that he and his wife are getting ready to make a deposit on a house near the company headquarters. From a work standpoint, you know that you shouldn’t divulge the information. From a friendship standpoint, though, you feel it’s your duty to tell your friend. Wouldn’t he tell you if the situation were reversed? So what do you do? As tempting as it is to be loyal to your friend, you shouldn’t. As an employee, your primary responsibility is to your employer. You might be able to soften your dilemma by convincing a manager with the appropriate authority to tell your friend the bad news before he puts down his deposit.

Whistle-Blowing

As we’ve seen, the misdeeds of Betty Vinson and her accomplices at WorldCom didn’t go undetected. They caught the eye of Cynthia Cooper, the company’s director of internal auditing. Cooper, of course, could have looked the other way, but instead she summoned up the courage to be a whistle-blower—an individual exposes illegal or unethical behavior in an organization. Like Vinson, Cooper had majored in accounting at Mississippi State and was a hard-working, dedicated employee. Unlike Vinson, however, she refused to be bullied by her boss, CFO Scott Sullivan. In fact, she had tried to tell not only Sullivan but also auditors from the huge Arthur Andersen accounting firm that there was a problem with WorldCom’s books. The auditors dismissed her warnings, and when Sullivan angrily told her to drop the matter, she started cleaning out her office. But she didn’t relent. She and her team worked late each night, conducting an extensive, secret investigation. Two months later, Cooper had evidence to take to Sullivan, who told her once again to back off. Again, however, she stood up to him, and though she regretted the consequences for her WorldCom coworkers, she reported the scheme to the company’s board of directors. Within days, Sullivan was fired and the largest accounting fraud in history became public.

As a result of Cooper’s actions, executives came clean about the company’s financial situation. The conspiracy of fraud was brought to an end, and though public disclosure of WorldCom’s problems resulted in massive stock-price declines and employee layoffs, investor and employee losses would have been greater without Cooper’s intervention.

Even though Cooper did the right thing, the experience wasn’t exactly gratifying. A lot of people applauded her action, but many coworkers shunned her; some even blamed her for the company’s troubles. She’s never been thanked by any senior executive at WorldCom. Five months after the fraud went public, new CEO Michael Capellas assembled what was left of the demoralized workforce to give them a pep talk on the company’s future. The senior management team mounted the stage and led the audience in a rousing rendition of “If you’re happy and you know it, clap your hands!” Cynthia Cooper wasn’t invited (Gostick & Telford, 2003).

Whistle-blowing often means career suicide. A survey of two hundred whistle-blowers conducted by the National Whistleblower Center found that half of them had been fired for blowing the whistle (National Whistleblower Center, 2002). Even those who get to keep their jobs experience painful repercussions. As long as they stay, some people will treat them (as one whistle-blower puts it) “like skunks at a picnic”; if they leave, they’re frequently blackballed in the industry (Dwyer, et. al., 2002). On a positive note, there’s the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which protects whistle-blowers under federal law.

For her own part, Cynthia Cooper doesn’t regret what she did. As she told a group of students at Mississippi State: “Strive to be persons of honor and integrity. Do not allow yourself to be pressured. Do what you know is right even if there may be a price to be paid” (Waller, 2003). If your company tells employees to do whatever it takes, push the envelope, look the other way, and “be sure that we make our numbers,” you have three choices: go along with the policy, try to change things, or leave. If your personal integrity is part of the equation, you’re probably down to the last two choices (Gostick & Telford, 2003).

Refusing to Rationalize

Despite all the good arguments in favor of doing the right thing, why do many reasonable people act unethically (at least at times)? Why do good people make bad choices? According to one study, there are four common rationalizations for justifying misconduct: (Gellerman, 2003)

- My behavior isn’t really illegal or immoral. Rationalizers try to convince themselves that an action is OK if it isn’t downright illegal or blatantly immoral. They tend to operate in a gray area where there’s no clear evidence that the action is wrong.

- My action is in everyone’s best interests. Some rationalizers tell themselves: “I know I lied to make the deal, but it’ll bring in a lot of business and pay a lot of bills.” They convince themselves that they’re expected to act in a certain way, forgetting the classic parental parable about jumping off a cliff just because your friends are (Gostick & Telford, 2003).

- No one will find out what I’ve done. Here, the self-questioning comes down to “If I didn’t get caught, did I really do it?” The answer is yes. There’s a simple way to avoid succumbing to this rationalization: Always act as if you’re being watched.

- The company will condone my action and protect me. This justification rests on a fallacy. Betty Vinson may honestly have believed that her actions were for the good of the company and that her boss would, therefore, accept full responsibility (as he promised). When she goes to jail, however, she’ll go on her own.

Here’s another rule of thumb: If you find yourself having to rationalize a decision, it’s probably a bad one. Over time, you’ll develop and hone your ethical decision-making skills.

Key Takeaways

- When you enter the business world, you’ll find yourself in situations in which you’ll have to choose the appropriate behavior.

- You’ll need to know how to distinguish a bribe from an acceptable gift.

- You’ll encounter situations that give rise to a conflict of interest—situations in which you’ll have to choose between taking action that promotes your personal interest and action that favors the interest of others.

- Sometimes you’ll be required to choose between loyalty to your employer and loyalty to a friend or family member.

- In business, as in all aspects of your life, you should act with honesty and integrity.

- At some point in your career, you might become aware of wrongdoing on the part of others and will have to decide whether to report the incident and become a whistle-blower—an individual who exposes illegal or unethical behavior in an organization.

-

Despite all the good arguments in favor of doing the right thing, some businesspeople still act unethically (at least at times). Sometimes they use one of the following rationalizations to justify their conduct:

- The behavior isn’t really illegal or immoral.

- The action is in everyone’s best interests.

- No one will find out what I’ve done.

- The company will condone my action and protect me.

Exercises

- Each December, Time magazine devotes its cover to the person who has made the biggest impact on the world that year. Time’s 2002 pick was not one person, but three: Cynthia Cooper (WorldCom), Coleen Rowley (the FBI), and Sherron Watkins (Enron). All three were whistle-blowers. We detailed Cynthia Cooper’s courage in exposing fraud at WorldCom in this chapter, but the stories of the other two whistle-blowers are equally worthwhile. Go to the Time.com Web site (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1003988,00.html) and read a posted story about Rowley, or visit the Time.com Web site (http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1003992,00.html) and read a posted story about Watkins. Then answer the following questions:

- What wrongdoing did the whistle-blower expose?

- What happened to her when she blew the whistle? Did she experience retaliation?

- Did she do the right thing? Would you have blown the whistle? Why or why not?

- You own a tax-preparation company with ten employees who prepare tax returns. In walking around the office, you notice that several of your employees spend a lot of time making personal use of their computers, checking personal e-mails, or shopping online. After doing an Internet search on employer computer monitoring, respond to these questions:

- Is it unethical for your employees to use their work computers for personal activities?

- Is it ethical for you to monitor computer usage?

- Do you have a legal right to do it?

- If you decide to monitor computer usage in the future, what rules would you make, and how would you enforce them?

References

Dwyer, P., et al., “Year of the Whistleblower,” BusinessWeek Online, December 16, 2002, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/02_50/b3812094.htm (accessed January 22, 2012).

Gellerman, S. W., “Why ‘Good’ Managers Make Bad Ethical Choices,” Harvard Business Review on Corporate Ethics (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003), 59.

Gostick, A., and Dana Telford, The Integrity Advantage (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2003), 103.

JCPenney Co., “Statement of Business Ethics for Associates and Officers: The ‘Spirit’ of This Statement,” http://ir.jcpenney.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=70528&p=irol-govconduct (accessed April 24, 2006).

National Whistleblower Center, “Labor Day Report: The National Status of Whistleblower Protection on Labor Day, 2002,” http://www.whistleblowers.org/labordayreport.htm (accessed April 24, 2006).

Waller, S., “Whistleblower Tells Students to Have Personal Integrity,” The (Jackson, MS) Clarion-Ledger, November 18, 2003, http://www.clarionledger.com/news/0311/18/b01.html (accessed April 24, 2006).