3.6 Corporate Social Responsibility

[Author removed at request of original publisher], Published by University of Minnesota

Corporate social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward different stakeholders when making legal, economic, ethical, and social decisions. What motivates companies to be “socially responsible” to their various stakeholders? We hope it’s because they want to do the right thing, and for many companies, “doing the right thing” is a key motivator. The fact is, it’s often hard to figure out what the “right thing” is: What’s “right” for one group of stakeholders isn’t necessarily just as “right” for another. One thing, however, is certain: Companies today are held to higher standards than ever before. Consumers and other groups consider not only the quality and price of a company’s products but also its character. If too many groups see a company as a poor corporate citizen, it will have a harder time attracting qualified employees, finding investors, and selling its products. Good corporate citizens, by contrast, are more successful in all these areas.

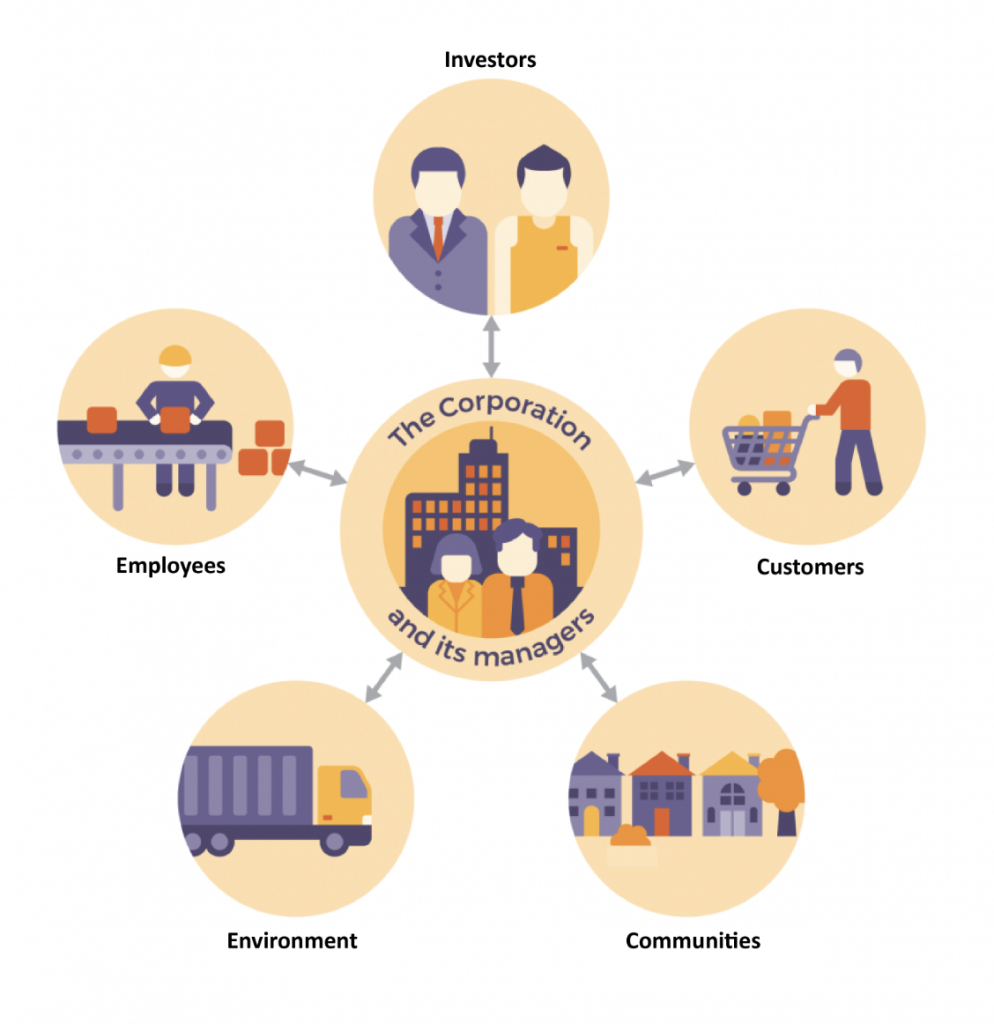

Figure 3.6 “The Corporate Citizen” presents a model of corporate responsibility based on a company’s relationships with its stakeholders. In this model, the focus is on managers—not owners—as the principals involved in all these relationships. Here, owners are the stakeholders who invest risk capital in the firm in expectation of a financial return. Other stakeholders include employees, suppliers, and the communities in which the firm does business. Proponents of this model hold that customers, who provide the firm with revenue, have a special claim on managers’ attention. The arrows indicate the two-way nature of corporation-stakeholder relationships: All stakeholders have some claim on the firm’s resources and returns, and it’s management’s job to make decisions that balance these claims (Baron, D. P., 2003).

Owners

Owners invest money in companies. In return, the people who run a company have a responsibility to increase the value of owners’ investments through profitable operations. Managers also have a responsibility to provide owners (as well as other stakeholders having financial interests, such as creditors and suppliers) with accurate, reliable information about the performance of the business. Clearly, this is one of the areas in which WorldCom managers fell down on the job. Upper-level management purposely deceived shareholders by presenting them with fraudulent financial statements.

Fiduciary Responsibilities

Finally, managers have a fiduciary responsibility to owners: They’re responsible for safeguarding the company’s assets and handling its funds in a trustworthy manner. This is a responsibility that was ignored by top executives at both Adelphia and Tyco, whose associates and families virtually looted company assets. To enforce managers’ fiduciary responsibilities for a firm’s financial statements and accounting records, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 requires CEOs and CFOs to attest to their accuracy. The law also imposes penalties on corporate officers, auditors, board members, and any others who commit fraud.

Employees

Companies are responsible for providing employees with safe, healthy places to work—as well as environments that are free from sexual harassment and all types of discrimination. They should also offer appropriate wages and benefits. In the following sections, we’ll take a closer look at each of these areas of responsibility.

Safety and Health

Though it seems obvious that companies should guard workers’ safety and health, a lot of them simply don’t. For over four decades, for example, executives at Johns Manville suppressed evidence that one of its products, asbestos, was responsible for the deadly lung disease developed by many of its workers (Gellerman, 2003). The company concealed chest X-rays from stricken workers, and executives decided that it was simply cheaper to pay workers’ compensation claims (or let workers die) than to create a safer work environment. A New Jersey court was quite blunt in its judgment: Johns Manville, it held, had made a deliberate, cold-blooded decision to do nothing to protect at-risk workers, in blatant disregard of their rights (Gellerman, 2003).

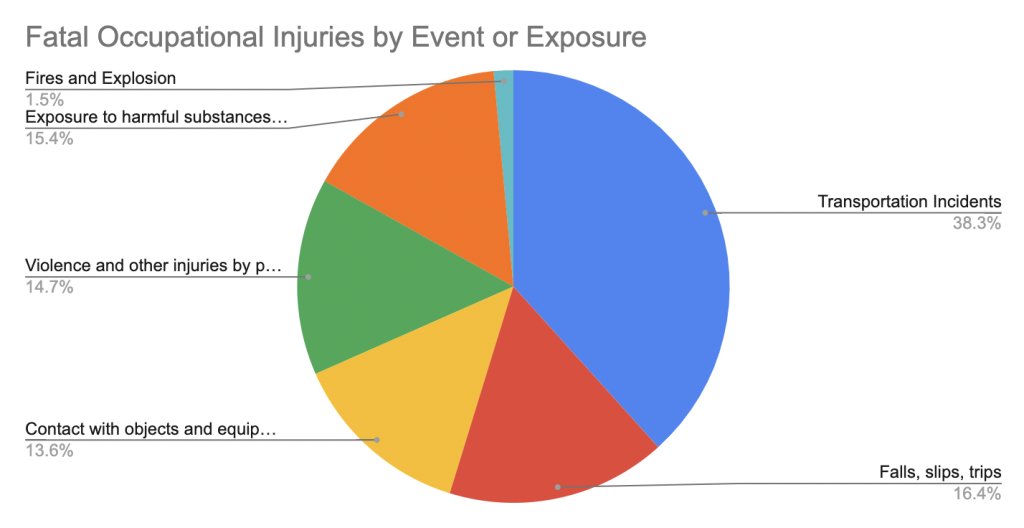

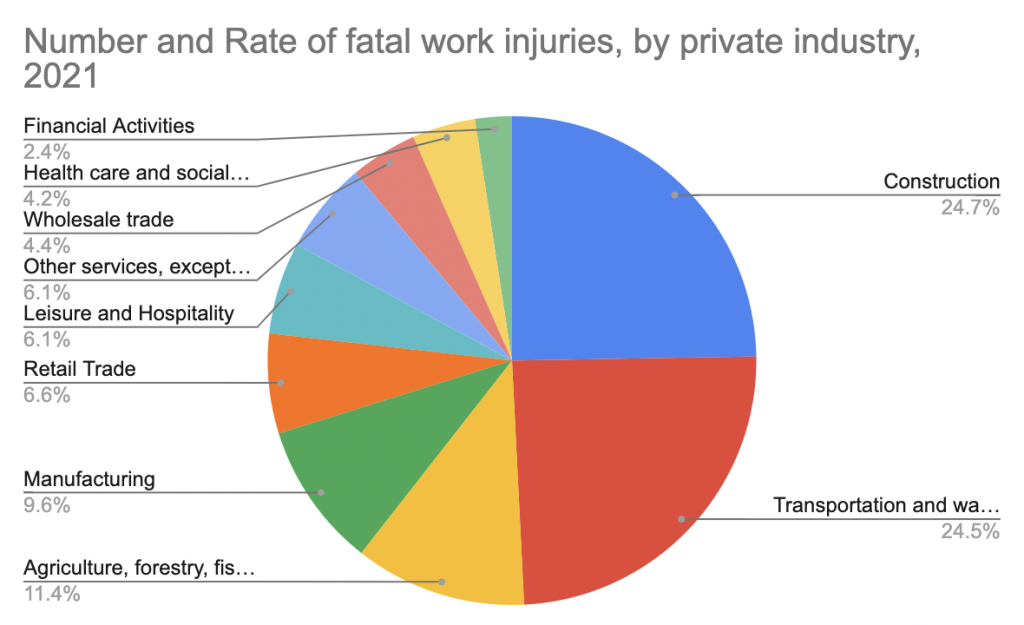

About four in one hundred thousand U.S. workers die in workplace “incidents” each year. The Department of Labor categorizes deaths caused by conditions like those at Johns Manville as “exposure to harmful substances or environments.” How prevalent is this condition as a cause of workplace deaths? See Figure 3.8: Workplace Deaths by Event or Exposure, 2010, which breaks down workplace fatalities by cause. Some jobs are more dangerous than others. For a comparative overview based on workplace deaths by occupation, see Figure 3.8: Number and Rate of fatal work injuries, by private industry

For most people, fortunately, things are better than they were at Johns Manville. Procter & Gamble (P&G), for example, considers the safety and health of its employees paramount and promotes the attitude that “Nothing we do is worth getting hurt for.” With nearly one hundred thousand employees worldwide, P&G uses a measure of worker safety called “total incident rate per employee,” which records injuries resulting in loss of consciousness, time lost from work, medical transfer to another job, motion restriction, or medical treatment beyond first aid. The company attributes the low rate of such incidents—less than one incident per hundred employees—to a variety of programs to promote workplace safety (Procter & Gamble, 2003).

Freedom from Sexual Harassment

What is sexual harassment? The law is quite precise:

- Sexual harassment occurs when an employee makes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature” to another employee who doesn’t welcome the advances.

- It’s also sexual harassment when “submission to or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.” (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2012)

To prevent sexual harassment—or at least minimize its likelihood—a company should adopt a formal anti-harassment policy describing prohibited conduct, asserting its objections to the behavior, and detailing penalties for violating the policy (Grossman, 2012). Employers also have an obligation to investigate harassment complaints. Failure to enforce anti-harassment policies can be very costly. In 1998, for example, Mitsubishi paid $34 million to more than three hundred fifty female employees of its Normal, Illinois, plant to settle a sexual harassment case supported by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC reprimanded the company for permitting an atmosphere of verbal and physical abuse against women, charging that female workers had been subjected to various forms of harassment, ranging from exposure to obscene graffiti and vulgar jokes to fondling and groping (Grossman, 2012).

Equal Opportunity and Diversity

People must be hired, evaluated, promoted, and rewarded on the basis of merit, not personal characteristics. This, too, is the law—namely, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Like most companies, P&G has a formal policy on hiring and promotion that forbids discrimination based on race, color, religion, gender, age, national origin, citizenship, sexual orientation, or disability. P&G expects all employees to support its commitment to equal employment opportunity and warns that those who violate company policies will face strict disciplinary action, including termination of employment (Procter & Gamble, 2012).

Equal Pay and the Wage Gap

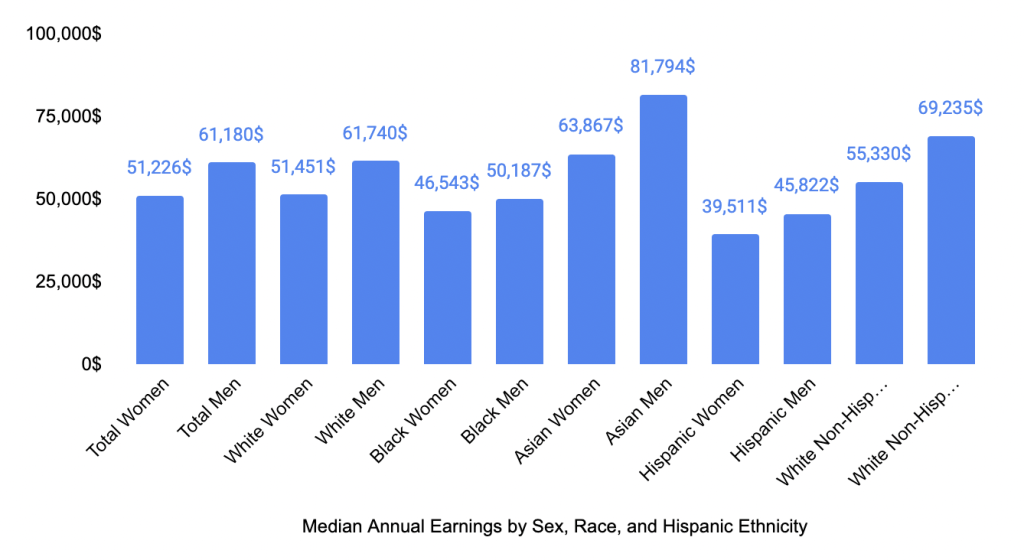

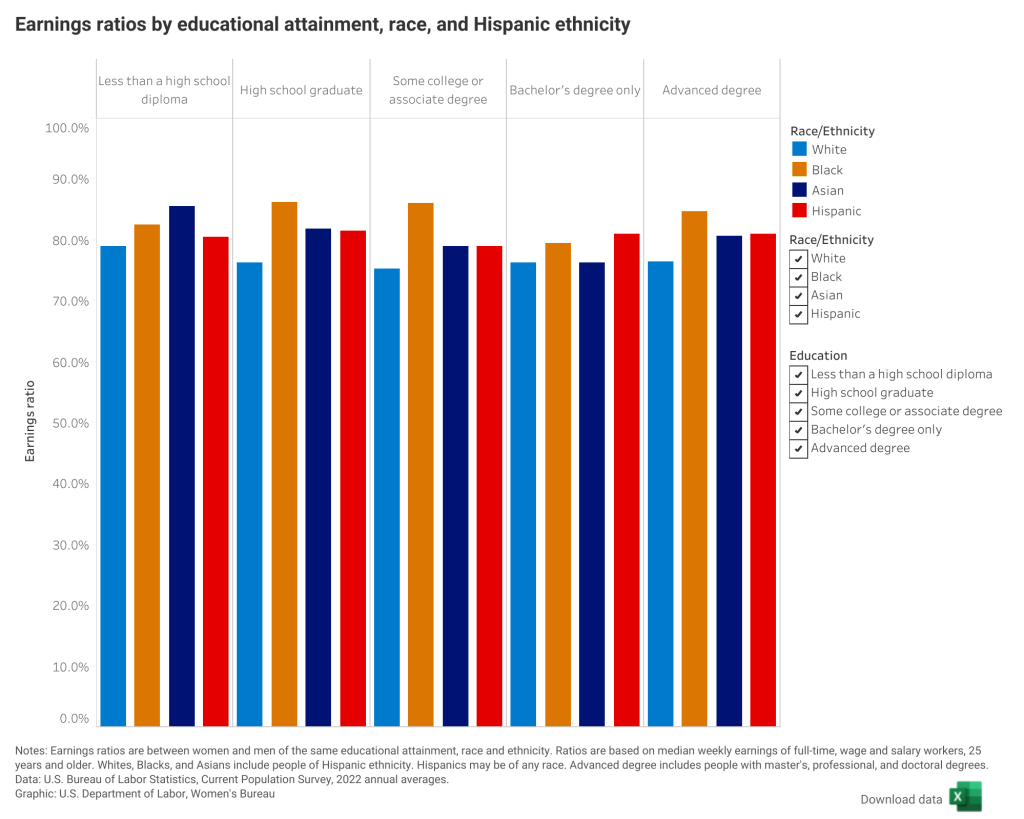

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 requires equal pay for both men and women in jobs that entail equal skill, equal effort, equal responsibility, or similar working conditions. What has been the effect of the law after forty years? In 1963, women earned, on average, $0.589 for every $1 earned by men. By 2010, that difference—which we call the wage gap—has been closed to $0.812 to $1, or approximately 81 percent (Aamodt, 2011). Figure 3.10: Median Annual Earnings by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Ethnicity provides some interesting numbers on the differences in annual earnings based not only on gender but on race, as well. Figure 3.11: Median Annual Earnings by Level of Education throws further light on the wage and unemployment gap when education is taken into consideration.

What accounts for the difference, despite the mandate of federal law? For one thing, the jobs typically held by women tend to pay less than those typically held by men. In addition, men often have better job opportunities. For example, a man newly hired at the same time as a woman will often get a higher-paying assignment at the entry level. Coupled with the fact that the same sort of discrimination applies when it comes to training and promotions, women are usually relegated to a lifetime of lower earnings.

Building Diverse Workforces

In addition to complying with equal employment opportunity laws, many companies make special efforts to recruit employees who are underrepresented in the workforce according to sex, race, or some other characteristic. In helping to build more diverse workforces, such initiatives contribute to competitive advantage for two reasons: (1) People from diverse backgrounds bring new talents and fresh perspectives to an organization, typically enhancing creativity in the development of new products. (2) By reflecting more accurately the changing demographics of the marketplace, a diverse workforce improves a company’s ability to serve an ethnically diverse population.

Wages and Benefits

At the very least, employers must obey laws governing minimum wage and overtime pay. A minimum wage is set by the federal government, though states can set their own rates. The current federal rate, for example, is $7.25, while the rate in the state of Washington is $8.67. When there’s a difference, the higher rate applies (U.S. Department of Labor, 2012). By law, employers must also provide certain benefits—social security (which provides retirement benefits), unemployment insurance (which protects against loss of income in case of job loss), and workers’ compensation (which covers lost wages and medical costs in case of on-the-job injury). Most large companies pay most of their workers more than minimum wage and offer considerably broader benefits, including medical, dental, and vision care, as well as pension benefits.

Customers

The purpose of any business is to satisfy customers, who reward businesses by buying their products. Sellers are also responsible—both ethically and legally—for treating customers fairly. The rights of consumers were first articulated by President John F. Kennedy in 1962 when he submitted to Congress a presidential message devoted to consumer issues (Waxman, 1993). Kennedy identified four consumer rights:

- The right to safe products. A company should sell no product that it suspects of being unsafe for buyers. Thus, producers have an obligation to safety-test products before releasing them for public consumption. The automobile industry, for example, conducts extensive safety testing before introducing new models (though recalls remain common).

- The right to be informed about a product. Sellers should furnish consumers with the product information that they need to make an informed purchase decision. That’s why pillows have labels identifying the materials used to make them, for instance.

- The right to choose what to buy. Consumers have a right to decide which products to purchase, and sellers should let them know what their options are. Pharmacists, for example, should tell patients when a prescription can be filled with a cheaper brand-name or generic drug. Telephone companies should explain alternative calling plans.

- The right to be heard. Companies must tell customers how to contact them with complaints or concerns. They should also listen and respond.

Companies share the responsibility for the legal and ethical treatment of consumers with several government agencies: the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which enforces consumer-protection laws; the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees the labeling of food products; and the Consumer Product Safety Commission, which enforces laws protecting consumers from the risk of product-related injury.

Communities

For obvious reasons, most communities see getting a new business as an asset and view losing one—especially a large employer—as a detriment. After all, the economic impact of business activities on local communities is substantial: They provide jobs, pay taxes, and support local education, health, and recreation programs. Both big and small businesses donate funds to community projects, encourage employees to volunteer their time, and donate equipment and products for a variety of activities. Larger companies can make greater financial contributions. Let’s start by taking a quick look at the philanthropic activities of a few U.S. corporations.

Financial Contributions

Many large corporations donate a percentage of sales or profits to worthwhile causes. Retailer Target, for example, donates 5 percent of its profits—about $2 million per week—to schools, neighborhoods, and local projects across the country; its store-based grants underwrite programs in early childhood education, the arts, and family-violence prevention (Target Brands Inc., 2011). The late actor Paul Newman donated 100 percent of the profits from “Newman’s Own” foods (salad dressing, pasta sauce, popcorn, and other products sold in eight countries). His company continues his legacy of donating all profits and distributing them to thousands of organizations, including the Hole in the Wall Gang camps for seriously ill children (Barrett, 2003; Newman, 2011).

Volunteerism

Many companies support employee efforts to help local communities. Patagonia, for example, a maker of outdoor gear and clothing, lets employees leave their jobs and work full-time for any environmental group for two months—with full salary and benefits; so far, more than 850 employees have taken advantage of the program (Patagonia, 2011).

Supporting Social Causes

Companies and executives often take active roles in initiatives to improve health and social welfare in the United States and elsewhere. Microsoft’s former CEO Bill Gates intends to distribute more than $3 billion through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which funds global health initiatives, particularly vaccine research aimed at preventing infectious diseases, such as polio (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2011), in undeveloped countries (Ackman, 2012). Noting that children from low-income families have twice as many cavities and often miss school because of dental-related diseases, P&G invested $1 million a year to set up “cavity-free zones” for 3.3 million economically disadvantaged children at Boys and Girls Clubs nationwide. In addition to giving away toothbrushes and toothpaste, P&G provided educational programs on dental hygiene. At some locations, the company even maintained clinics providing affordable oral care to poor children and their families (Kotler & Lee, 2004). Proctor & Gamble recently committed to provide more than two billion liters of clean drinking water to adults and children living in poverty in developing countries. The company believes that this initiative will save an estimated ten thousand lives (Procter & Gamble web site, 2011).

Key Takeaways

- Corporate social responsibility refers to the approach that an organization takes in balancing its responsibilities toward different stakeholders when making legal, economic, ethical, and social decisions.

- Companies are socially responsible to their various stakeholders—owners, employees, customers, and the communities in which they conduct business.

- Owners invest money in companies. In return, the people who manage companies have a responsibility to increase the value of owners’ investments through profitable operations.

- Managers have a responsibility to provide owners and other stakeholders with accurate, reliable financial information.

- They also have a fiduciary responsibility to safeguard the company’s assets and handle its funds in a trustworthy manner.

- Companies have a responsibility to guard workers’ safety and health and to provide them with a work environment that’s free from sexual harassment.

- Businesses should pay appropriate wages and benefits, treat all workers fairly, and provide equal opportunities for all employees.

- Many companies have discovered the benefits of valuing diversity. People with diverse backgrounds bring new talents and fresh perspectives, and improve a company’s ability to serve an ethically diverse population.

- Sellers are responsible—both ethically and legally—for treating customers fairly. Consumers have certain rights: to use safe products, to be informed about products, to choose what to buy, and to be heard.

-

Companies also have a responsibility to the communities in which they produce and sell their products. The economic impact of businesses on local communities is substantial. Companies have the following functions:

- Provide jobs

- Pay taxes

- Support local education, health, and recreation activities

- Donate funds to community projects

- Encourage employees to volunteer their time

- Donate equipment and products for a variety of activities

Exercises

- Nonprofit organizations (such as your college or university) have social responsibilities to their stakeholders. Identify your school’s stakeholders. For each category of stakeholder, indicate the ways in which your school is socially responsible to that group.

- Pfizer is one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the United States. It’s in the business of discovering, developing, manufacturing, and marketing prescription drugs. While it’s headquartered in New York, it sells products worldwide, and its corporate responsibility initiatives also are global. Go to the Pfizer Web site (http://www.pfizer.com/responsibility/global_health/global_health.jsp) and read about the firm’s global corporate-citizenship initiatives (listed on the left sidebar). Write a brief report describing the focus of Pfizer’s efforts and identifying a few key programs. In your opinion, why should U.S. companies direct corporate-responsibility efforts at people in countries outside the United States?

References

Aamodt, M., “Human Resource Statistics,” Radford University, http://maamodt.asp.radford.edu/HR%20Statistics/Salary%20by%20Sex%20and%20Race.htm (accessed August 15, 2011).

Ackman, D., “Bill Gates Is a Genius and You’re Not,” Forbes.com, July 21, 2004, http://www.forbes.com/2004/07/21/cx_da_0721topnews.html (accessed January 22, 2012).

Baron, D. P., Business and Its Environment, 4th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), 650–52.

Barrett, J., “A Secret Recipe for Success: Paul Newman and A. E. Hotchner Dish Up Management Tips from Newman’s Own,” Newsweek, November 3, 2003, http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-109357986.html (accessed January 22, 2012).

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, “2011 Annual Letter from Bill Gates,” http://www.gatesfoundation.org/annual-letter/2011/Pages/home.aspx (accessed August 15, 2011).

Gellerman, S. W., “Why ‘Good’ Managers Make Bad Ethical Choices,” Harvard Business Review on Corporate Ethics (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003), 49–66.

Grossman, J., “Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: Do Employers’ Efforts Truly Prevent Harassment, or Just Prevent Liability,” Find Laws Legal Commentary, Writ, http://writ.news.findlaw.com/grossman/20020507.html (accessed January 22, 2012).

Kotler, P., and Nancy Lee, “Best of Breed,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, Spring 2004, 21.

Newman, P., “Our Story,” Newman’s Own Web site, http://www.newmansown.com/ourstory.aspx (accessed August 15, 2011).

Patagonia Web site, “Environmental Internships,” http://www.patagonia.com/us/patagonia.go?assetid=1963 (accessed August 15, 2011).

Procter & Gamble, “Respect in the Workplace,” Our Values and Policies, http://www.pg.com/content/pdf/01_about_pg/01_about_pg_homepage/about_pg_toolbar/download_report/values_and_policies.pdf (accessed January 22, 2012).

Procter & Gamble, 2003 Sustainability Report, http://www.pg.com/content/pdf/01_about_pg/corporate_citizenship/sustainability/reports/sustainability_report_2003.pdf (accessed April 24, 2006).

Procter & Gamble Web site, “Social Responsibility, P&G Children’s Safe Drinking Water Program,” Proctor & Gamble Web site, http://www.pg.com/en_US/sustainability/social_responsibility/childrens_safe_water.shtml (accessed August 15, 2011).

Target Brands Inc., “Target Gives Back over $2 Million a Week to Education, the Arts and Social Services,” http://target.com/target_group/community_giving/index.jhtml (accessed August 15, 2011).

U.S. Department of Labor, “Minimum Wage Laws in the States,” http://www.dol.gov/esa/minwage/america.htm (accessed January 22, 2012).

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “Facts about Sexual Harassment,” http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/fs-sex.html (accessed January 22, 2012).

Waxman, H. A., House of Representatives, “Remarks on Proposed Consumer Bill of Rights Day, Extension of Remarks,” March 15, 1993, http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?r103:E15MR30-90 (accessed April 24, 2006), 1–2.

deals with actions that affect a variety of parties in a company’s environment

presents a model of corporate responsibility based on a company’s relationships with its stakeholders

invest money in companies

They’re responsible for safeguarding the company’s assets and handling its funds in a trustworthy manner

occurs when an employee makes “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature” to another employee who doesn’t welcome the advances

prohibited conduct, asserting its objections to the behavior, and detailing penalties for violating the policy