11.1 Diversity and Inclusion in the Workforce

Lawrence J. Gitman, et al

Effective business managers in the twenty-first century need to be aware of a broad array of ethical choices they can make that affect their employees, their customers, and society as a whole. What these decisions have in common is the need for managers to recognize and respect the rights of all.

Actively supporting human diversity at work, for instance, benefits the business organization as well as society on a broader level. Thus, ethical managers recognize and accommodate the special needs of some employees, show respect for workers’ different faiths, appreciate and accept their differing sexual orientations and identification, and ensure pay equity for all. Ethical managers are also tuned in to public sentiment, such as calls by stakeholders to respect the rights of animals, and they monitor trends in these social attitudes, especially on social media.

How would you, as a manager, ensure a workplace that values inclusion and diversity? How would you respond to employees who resisted such a workplace? How would you approach broader social concerns such as income inequality or animal rights? This chapter introduces the potential impacts on business of some of the most pressing social themes of our time, and it discusses ways managers can respect the rights of all and improve business results by choosing an ethical path.

Diversity and Inclusion in the Workforce

Diversity is not simply a box to be checked; rather, it is an approach to business that unites ethical management and high performance. Business leaders in the global economy recognize the benefits of a diverse workforce and see it as an organizational strength, not as a mere slogan or a form of regulatory compliance with the law. They recognize that diversity can enhance performance and drive innovation; conversely, adhering to the traditional business practices of the past can cost them talented employees and loyal customers.

A study by global management consulting firm McKinsey & Company indicates that businesses with gender and ethnic diversity outperform others. According to Mike Dillon, chief diversity and inclusion officer for PwC in San Francisco, “attracting, retaining and developing a diverse group of professionals stirs innovation and drives growth.”[1]Living this goal means not only recruiting, hiring, and training talent from a wide demographic spectrum but also including all employees in every aspect of the organization.

Workplace Diversity

The twenty-first century workplace features much greater diversity than was common even a couple of generations ago. Individuals who might once have faced employment challenges because of religious beliefs, ability differences, or sexual orientation now regularly join their peers in interview pools and on the job. Each may bring a new outlook and different information to the table; employees can no longer take for granted that their coworkers think the same way they do. This pushes them to question their own assumptions, expand their understanding, and appreciate alternate viewpoints. The result is more creative ideas, approaches, and solutions. Thus, diversity may also enhance corporate decision-making.

Communicating with those who differ from us may require us to make an extra effort and even change our viewpoint, but it leads to better collaboration and more favorable outcomes overall, according to David Rock, director of the Neuro-Leadership Institute in New York City, who says diverse coworkers “challenge their own and others’ thinking.”[2]According to the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), organizational diversity now includes more than just racial, gender, and religious differences. It also encompasses different thinking styles and personality types, as well as other factors such as physical and cognitive abilities and sexualorientation, all of which influence the way people perceive the world. “Finding the right mix of individuals to work on teams, and creating the conditions in which they can excel, are key business goals for today’s leaders, given that collaboration has become a paradigm of the twenty-first century workplace,” according to an SHRM article.[3]

Attracting workers who are not all alike is an important first step in the process of achieving greater diversity. However, managers cannot stop there. Their goals must also encompass inclusion, or the engagement of all employees in the corporate culture. “The far bigger challenge is how people interact with each other once they’re on the job,” says Howard J. Ross, founder and chief learning officer at Cook Ross, a consulting firm specializing in diversity. “Diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance. Diversity is about the ingredients, the mix of people and perspectives. Inclusion is about the container—the place that allows employees to feel they belong, to feel both accepted and different.”[4]

Workplace diversity is not a new policy idea; its origins date back to at least the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (CRA) or before. Census figures show that women made up less than 29 percent of the civilian workforce when Congress passed Title VII of the CRA prohibiting workplace discrimination. After the passage of the law, gender diversity in the workplace expanded significantly. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the percentage of women in the labor force increased from 48 percent in 1977 to a peak of 60 percent in 1999. Over the last five years, the percentage has held relatively steady at 57 percent. Over the past forty years, the total number of women in the labor force has risen from 41 million in 1977 to 71 million in 2017.[5]The BLS projects that the number of women in the U.S. labor force will reach 92 million in 2050 (an increase that far outstrips population growth).

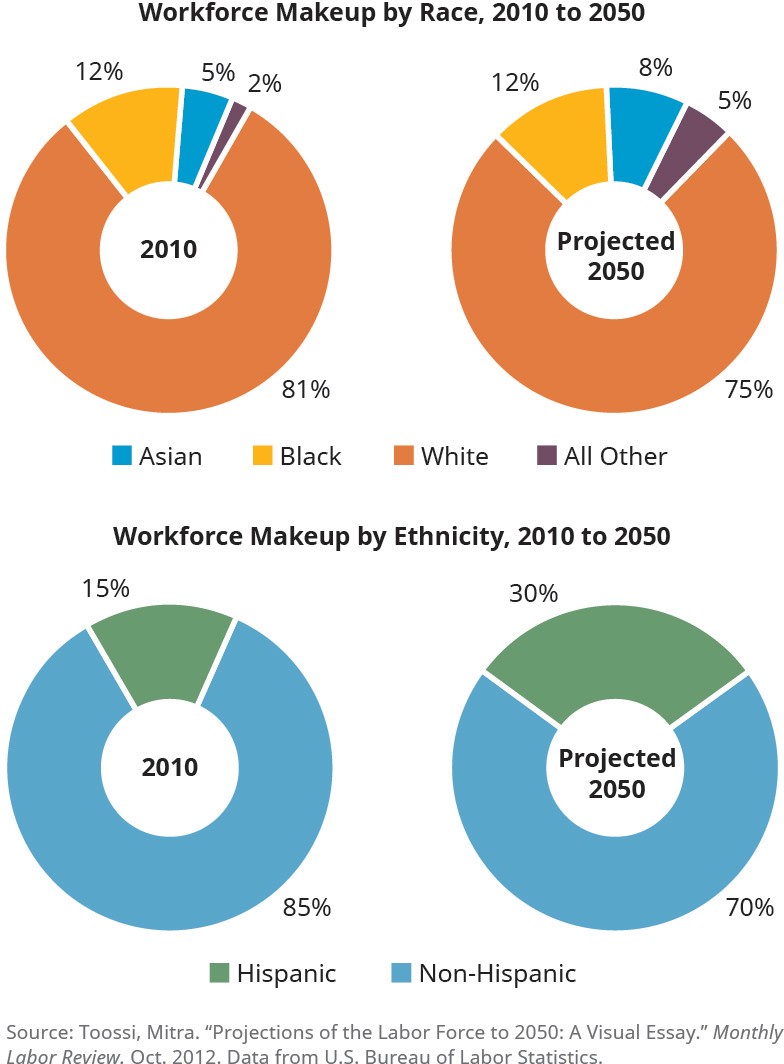

The statistical data show a similar trend for African American, Asian American, and Hispanic workers. Just before the passage of the CRA in 1964, the percentages of minorities in the official on-the-books workforce were relatively small compared with their representation in the total population. In 1966, Asians accounted for just 0.5 percent of private-sector employment, with Hispanics at 2.5 percent and African Americans at 8.2 percent.[6]However, Hispanic employment numbers have significantly increased since the CRA became law; they are expected to more than double from 15 percent in 2010 to 30 percent of the labor force in 2050. Similarly, Asian Americans are projected to increase their share from 5 to 8 percent between 2010 and 2050.

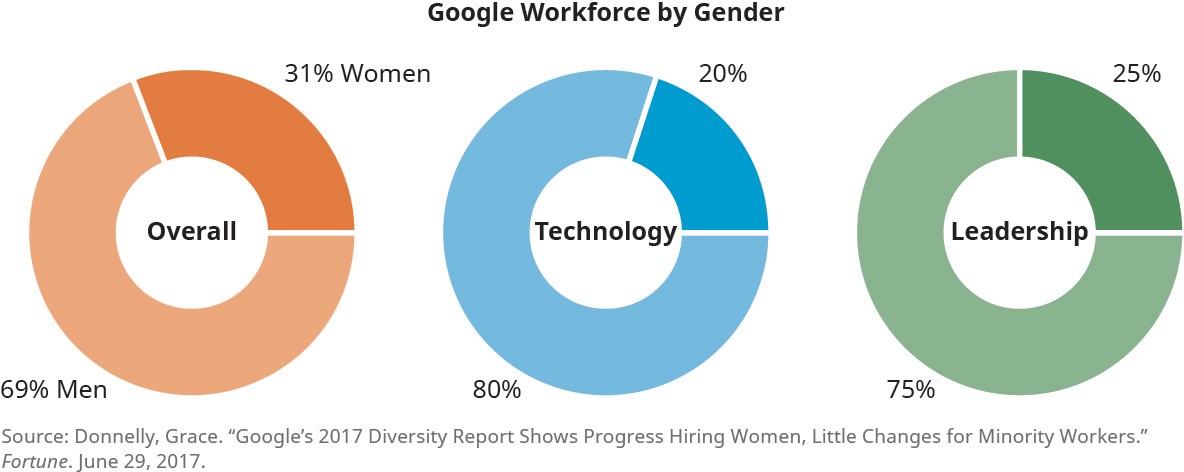

Much more progress remains to be made, however. For example, many people think of the technology sector as the workplace of open-minded millennials. Yet Google, as one example of a large and successful company, revealed in its latest diversity statistics that its progress toward a more inclusive workforce may be steady but it is very slow. Men still account for the great majority of employees at the corporation; just over 30 percent are women, and women fill just 20 percent of Google’s technical roles (Figure 11.2). The company has shown a similar lack of gender diversity in leadership roles, where women hold 25 percent of positions. Despite modest progress, an ocean-sized gap remains to be narrowed. When it comes to ethnicity, approximately 56 percent of Google employees are white. About 35 percent are Asian, 3.5 percent are Latino, and 2.4 percent are black, and of the company’s management and leadership roles, 68 percent are held by whites. [7]

Google is not alone in coming up short on diversity. Recruiting and hiring a diverse workforce has been a challenge for most major technology companies, including Facebook, Apple, and Yahoo (now owned by Verizon); all have reported gender and ethnic shortfalls in their workforces.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has made available 2014 data comparing the participation of women and minorities in the high-technology sector with their participation in U.S. private- sector employment overall, and the results show the technology sector still lags.[8]Compared with all private- sector industries, the high-technology industry employs a larger share of whites (68.5%), Asian Americans (14%), and men (64%), and a smaller share of African Americans (7.4%), Latinos (8%), and women (36%). Whites also represent a much higher share of those in the executive category (83.3%), whereas other groups hold a significantly lower share, including African Americans (2%), Latinos (3.1%), and Asian Americans (10.6%). In addition, and perhaps not surprisingly, 80 percent of executives are men and only 20 percent are women. This compares negatively with all other private-sector industries, in which 70 percent of executives are men and 30 percent women. Technology companies are generally not trying to hide the problem. Many have been publicly releasing diversity statistics since 2014, and they have been vocal about their intentions to close diversity gaps. More than thirty technology companies, including Intel, Spotify, Lyft, Airbnb, and Pinterest, each signed a written pledge to increase workforce diversity and inclusion, and Google pledged to spend more than $100 million to address diversity issues.[9]

Diversity and inclusion are positive steps for business organizations, and despite their sometimes slow pace, the majority are moving in the right direction. Diversity strengthens the company’s internal relationships with employees and improves employee morale, as well as its external relationships with customer groups. Communication, a core value of most successful businesses, becomes more effective with a diverse workforce. Performance improves for multiple reasons, not the least of which is that acknowledging diversity and respecting differences is the ethical thing to do.[10]

“Blind spots: Challenge assumptions” discusses the significance of uncovering our hidden biases and beliefs to foster an increasingly inclusive and collaborative workplace environment. By acknowledging the existence of these subconscious thoughts and challenging them, colleagues from diverse backgrounds and experiences can begin to more effectively work together. This can also support a workplace culture that ensures people feel seen and heard.

Adding Value through Diversity

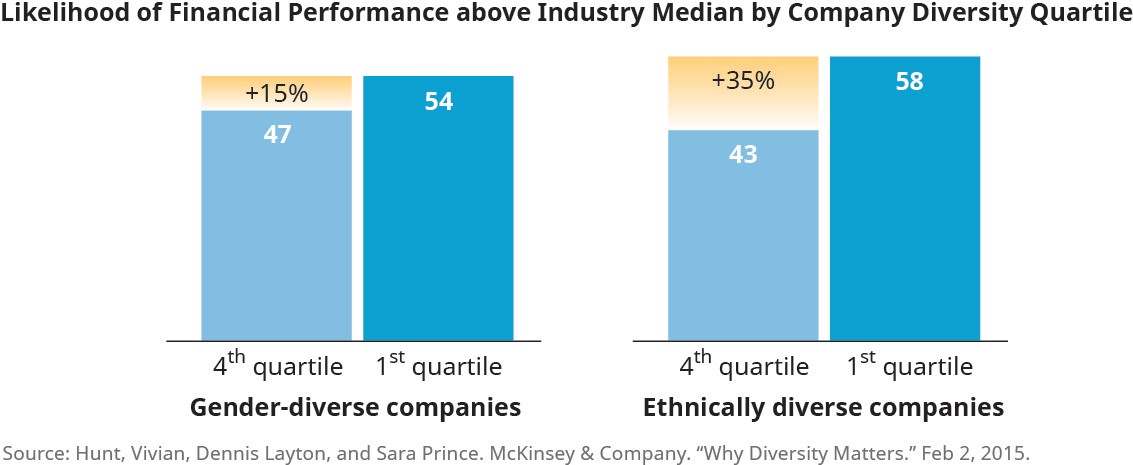

Diversity need not be a financial drag on a company, measured as a cost of compliance with no return on the investment. A recent McKinsey & Company study concluded that companies that adopt diversity policies do well financially, realizing what is sometimes called a diversity dividend. The study results demonstrated a statistically significant relationship of better financial performance from companies with a more diverse leadership team, as indicated in Figure 11.3. Companies in the top 25 percent in terms of gender diversity were 15 percent more likely to post financial returns above their industry median in the United States. Likewise, companies in the top 25 percent of racial and/or ethnic diversity were 35 percent more likely to show returns exceeding their respective industry median. [11]

These results demonstrate a positive correlation between diversity and performance, rebutting any claim that affirmative action and other such programs are social engineering that constitutes a financial drag on earnings. In fact, the results reveal a negative correlation between performance and lack of diversity, with companies in the bottom 25 percent for gender and ethnicity or race proving to be statistically less likely to achieve above-average financial returns than the average companies. Non-diverse companies were not leaders in performance indicators. Positive correlations do not equal causation, of course, and greater gender and ethnic diversity do not automatically translate into profit. Rather, as this chapter shows, they enhance creativity and decision-making, employee satisfaction, an ethical work environment, and customer goodwill, all of which, in turn, improve operations and boost performance.

Diversity is not a concept that matters only for the rank-and-file workforce; it makes a difference at all levels of an organization. The McKinsey & Company study, which examined twenty thousand firms in ninety countries, also found that companies in the top 25 percent for executive and/or board diversity had returns on equity more than 50 percent higher than those companies that ranked in the lowest 25 percent. Companies with a higher percentage of female executives tended to be more profitable.[12]

Achieving equal representation in employment based on demographic data is the ethical thing to do because it represents the essential American ideal of equal opportunity for all. It is a basic assumption of an egalitarian society that all have the same chance without being hindered by immutable characteristics. However, there are also directly relevant business reasons to do it. More diverse companies perform better, as we saw earlier in this chapter, but why? The reasons are intriguing and complex. Among them are that diversity improves a company’s chances of attracting top talent and that considering all points of view may lead to better decision- making. Diversity also improves customer experience and employee satisfaction.

To achieve improved results, companies need to expand their definition of diversity beyond race and gender. For example, differences in age, experience, and country of residence may result in a more refined global mind-set and cultural fluency, which can help companies succeed in international business. A salesperson may know the language of customers or potential customers from a specific region or country, for example, or a customer service representative may understand the norms of another culture. Diverse product-development teams can grasp what a group of customers may want that is not currently being offered.

Resorting to the same approaches repeatedly is not likely to result in breakthrough solutions. Diversity, however, provides usefully divergent perspectives on the business challenges companies face. New ideas help solve old problems—another way diversity makes a positive contribution to the bottom line.

The Challenges of a Diverse Workforce

Diversity is not always an instant success; it can sometimes introduce workplace tensions and lead to significant challenges for a business to address. Some employees simply are slow to come around to a greater appreciation of the value of diversity because they may never have considered this perspective before. Others may be prejudiced and consequently attempt to undermine the success of diversity initiatives in general. In 2017, for example, a senior software engineer’s memo criticizing Google’s diversity initiatives was leaked, creating significant protests on social media and adverse publicity in national news outlets.[13]The memo asserted “biological causes” and “men’s higher drive for status” to account for women’s unequal representation in Google’s technology departments and leadership.

Google’s response was quick. The engineer was fired, and statements were released emphasizing the company’s commitment to diversity.[14]Although Google was applauded for its quick response, however, some argued that an employee should be free to express personal opinions without punishment (despite the fact that there is no right of free speech while at work in the private sector).

In the latest development, the fired engineer and a coworker filed a class-action lawsuit against Google on behalf of three specific groups of employees who claim they have been discriminated against by Google: whites, conservatives, and men.[15]This is not just the standard “reverse discrimination” lawsuit; it goes to the heart of the culture of diversity and one of its greatest challenges for management—the backlash against change.

In February 2018, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that Google’s termination of the engineer did not violate federal labor law[16] and that Google had discharged the employee only for inappropriate but unprotected conduct or speech that demeaned women and had no relationship to any terms of employment. Although this ruling settles the administrative labor law aspect of the case, it has no effect on the private wrongful termination lawsuit filed by the engineer, which is still proceeding.

Yet other employees are resistant to change in whatever form it takes. As inclusion initiatives and considerations of diversity become more prominent in employment practices, wise leaders should be prepared to fully explain the advantages to the company of greater diversity in the workforce as well as making the appropriate accommodations to support it. Accommodations can take various forms. For example, if you hire more women, should you change the way you run meetings so everyone has a chance to be heard? Have you recognized that women returning to work after childrearing may bring improved skills such as time management or the ability to work well under pressure? If you are hiring more people of different faiths, should you set aside a prayer room? Should you give out tickets to football games as incentives? Or build team spirit with trips to a local bar? Your managers may need to accept that these initiatives may not suit everyone. Adherents of some faiths may abstain from alcohol, and some people prefer cultural events to sports. Many might welcome a menu of perquisites (“perks”) from which to choose, and these will not necessarily be the ones that were valued in the past. Mentoring new and diverse peers can help erase bias and overcome preconceptions about others. However, all levels of a company must be engaged in achieving diversity, and all must work together to overcome resistance.

“Inclusion Starts With I” speaks to how bias can appear in various ways, some well recognized and obvious, while others may not be. But each member of an organization can work to better understand their own biases, and the need for action beyond simply stating the importance of inclusivity. By implementing tangible accommodations and initiatives, organizations can create an environment where employees feel seen and supported. But ultimately it requires the support and engagement of everyone to fully realize the benefits of inclusion.

CASES FROM THE REAL WORLD

Companies with Diverse Workforces

Texas Health Resources, a Dallas-area healthcare and hospital company, ranked No. 1 among Fortune’s Best Workplaces for Diversity and No. 2 for Best Workplaces for African Americans.[17]Texas Health employs a diverse workforce that is about 75 percent female and 40 percent minority. The company goes above and beyond by offering English classes for Hispanic workers and hosting several dozen social and professional events each year to support networking and connections among peers with different backgrounds. It also offers same-sex partner benefits; approximately 3 percent of its workforce identifies as LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning).

Another company receiving recognition is Marriott International, ranked No. 6 among Best Workplaces for Diversity and No. 7 among Best Workplaces for African Americans and for Latinos. African American, Latino, and other ethnic minorities account for about 65 percent of Marriott’s 100,000 employees, and 15 percent of its executives are minorities. Marriott’s president and CEO, Arne Sorenson, is recognized as an advocate for LGBTQ equality in the workplace, published an open letter on LinkedIn expressing his support for diversity and entreating then president-elect Donald Trump to use his position to advocate for inclusiveness. “Everyone, no matter their sexual orientation or identity, gender, race, religion disability or ethnicity should have an equal opportunity to get a job, start a business or be served by a business,” Sorenson wrote. “Use your leadership to minimize divisiveness around these areas by letting people live their lives and by ensuring that they are treated equally in the public square.”[18]

Critical Thinking

Is it possible that Texas Health and Marriott rank highly for diversity because the hospitality and healthcare industries tend to hire more women and minorities in general? Why or why not?

Key Takeaways

- A diverse workforce yields many positive outcomes for a company.

- Access to a deep pool of talent, positive customer experiences, and strong performance are all documented positives.

- Diversity may also bring some initial challenges, and some employees can be reluctant to see its advantages, but committed managers can deal with these obstacles effectively and make diversity a success through inclusion.

- Novid Parsi, “Workplace Diversity and Inclusion Gets Innovative,” Society for Human Resource Management, January 16, 2017. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0217/pages/disrupting-diversity-in-the-workplace.aspx. ↵

- Novid Parsi, “Workplace Diversity and Inclusion Gets Innovative,” Society for Human Resource Management, January 16, 2017. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0217/pages/disrupting-diversity-in-the-workplace.aspx. ↵

- Novid Parsi, “Workplace Diversity and Inclusion Gets Innovative,” Society for Human Resource Management, January 16, 2017. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0217/pages/disrupting-diversity-in-the-workplace.aspx. ↵

- Novid Parsi, “Workplace Diversity and Inclusion Gets Innovative,” Society for Human Resource Management, January 16, 2017. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0217/pages/disrupting-diversity-in-the-workplace.aspx. ↵

- “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Household Data Annual Averages. 2. Employment Status of the Civilian Noninstitutional Population 16 Years and Over by Sex, 1977 to date,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat02.htm (accessed July 22, 2018). ↵

- “Indicators (2013),” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/employment/jobpat-eeo1/2013_indicators.cfm (accessed January 10, 2018). ↵

- Google, https://diversity.google/annual-report/# (accessed July 10, 2018). ↵

- “Diversity in High Tech,” U.S. EEOC. https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/reports/hightech/ (accessed January 12, 2018). ↵

- Lisa Eadicicco, “Google’s Diversity Efforts Still Have a Long Way to Go,” Time, July 1, 2016. http://time.com/4391031/google-diversity-statistics-2016/. ↵

- Pubali Neogy, “Diversity in Workplace Can Be a Game Changer,” Yahoo India Finance, June 18, 2018. Neogy states that greater diversity in the workplace fosters “creativity and innovation,” “opens global opportunities” for the firm, “fosters adaptability and better working culture,” and generally “improves companies’ bottom lines.” https://in.finance.yahoo.com/news/diversity-workplace-can-game-changer-heres-183319670.html. ↵

- Vivian Hunt, Dennis Layton, and Sara Prince, “Why Diversity Matters,” McKinsey & Company, January 2015. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/why-diversity-matters. ↵

- Marcus Noland, Tyler Moran, and Barbara Kotschwar, “Is Gender Diversity Profitable? Evidence from a Global Survey,” Working Paper 16-3, Peterson Institute for International Economics, February 2016. https://piie.com/publications/working-papers/gender-diversity-profitable-evidence-global-survey. ↵

- Daisuke Wakabayashi, “Contentious Memo Strikes Nerve inside Google and Out,” New York Times, August 8, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/08/technology/google-engineer-fired-gender-memo.html. ↵

- Bill Chappell and Laura Sydell, “Google Reportedly Fires Employee Who Slammed Diversity Efforts,” National Public Radio, August 7, 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/08/07/542020041/google-grapples-with-fallout-after-employee-slams-diversity-efforts. ↵

- Sara Ashley O’Brien, “Engineers Sue Google for Allegedly Discriminating against White Men and Conservatives,” CNN/Money, January 8, 2018. http://money.cnn.com/2018/01/08/technology/james-damore-google-lawsuit/index.html. ↵

- Daisuke Wakabayashi, “Google Legally Fired Diversity Memo Author, Labor Agency Says,” New York Times, February 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/16/business/google-memo-firing.html. ↵

- Michael Bush and Kim Peters, “How the Best Companies Do Diversity Right,” Fortune, December 5, 2016. http://fortune.com/2016/12/05/diversity-inclusion-workplaces/. ↵

- Michael Bush and Kim Peters, “How the Best Companies Do Diversity Right,” Fortune, December 5, 2016. http://fortune.com/2016/12/05/diversity-inclusion-workplaces/. ↵

the engagement of all employees in the corporate culture

the financial benefit of improved performance resulting from a diverse workforce