20.3 Negligence Torts

[Author removed at request of original publisher], Published by University of Minnesota

We can now get back to your role in this case, though doing so means first taking a closer look at further aspects of your roommate’s role. You and your roommate are being sued by the homeowner for a different type of tort—a negligence tort, which results not from intentional wrongdoing, but from carelessness. When he placed that can of paint at his feet, where he might easily dislodge it as he moved around the platform, your roommate allowed his conduct to fall below a certain standard of care—namely, the degree of care necessary to protect others from an unreasonable likelihood of harm.

Elements of a Negligence Claim

To prove that the act in question was negligent, the homeowner must demonstrate the four elements of a negligence claim (Cheesman, 2006):

- That the defendant (your roommate and, ultimately, you) owed a duty of care to the plaintiff (the homeowner). Duty of care refers simply to the basic obligation that one person owes another—the duty not to cause harm or an unreasonable risk of harm.

- That the defendant breached his duty of care. Once it has been determined that the defendant owed a duty of care, the court will ask whether he did indeed fail to perform that duty. Did he, in other words, fail to act as a reasonable person would act? (In your roommate’s case, by the way, it’s a question of acting as a reasonable professional would act.)

- That the defendant’s breach of duty of care caused injury to the plaintiff or the plaintiff’s property. If the bucket of paint had fallen on his own car, your roommate’s carelessness wouldn’t have been actionable—wouldn’t have provided cause for legal action—because the plaintiff (the homeowner) would have suffered no injury to person or property. What if the paint bucket had hit and shattered the homeowner’s big toe, thus putting an end to his career as a professional soccer player? In that case, you and your roommate would be looking at much higher damages. As it stands, the homeowner can seek compensation only to cover the damage to his car.

- That the defendant’s action did in fact cause the injury in question. There must be a direct cause-and-effect relationship between the defendant’s action and the plaintiff’s injury. In law, this relationship is called a cause in fact or actual cause. For example, what if the homeowner had taken one look at his dented, paint-spattered car and collapsed from a heart attack? Would your roommate be liable for this injury to the plaintiff’s person? Possibly, though probably not. Most actions of any kind set in motion a series of consequent actions, and the court must decide the point beyond which a defendant is no longer liable for these actions. The last point at which the defendant is liable for negligence is called a proximate cause or legal cause. The standard for determining proximate cause is generally foreseeability. Your roommate couldn’t reasonably foresee the possibility that the owner of the car beneath his platform might have a heart attack as a result of some mishap with his paint bucket. Thus he probably wouldn’t be held liable for this particular injury to the plaintiff’s person.

Negligence and Employer Liability

At this point, you yourself may still want to ask an important question: “Why me?” Why should you be held liable for negligence? Undoubtedly you owed your client (the homeowner) a duty of care, but you personally did nothing to breach that duty. And if you didn’t breach any duty of care, how could you have been the cause, either actual or proximate, of any injury suffered by your client? Where does he get off suing you for negligence?

The Law of Contracts

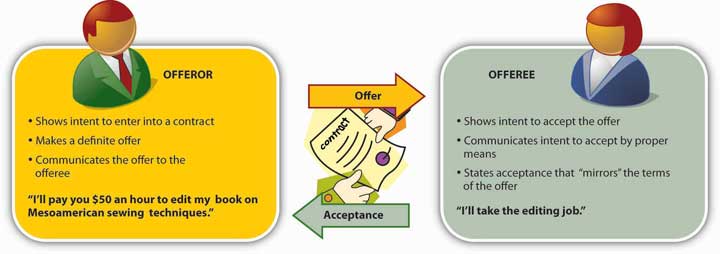

To answer these questions, we must enter an extremely important area of civil law—the law of contracts. A contract is an exchange of promises or an exchange of a promise for an act, and because it involves an exchange, it obviously involves at least two parties. As you can see in Figure 20.1: Parties to a Contract, an offeror makes an offer to enter into a contract with an offeree. The offeror offers to do something in particular (or to refrain from doing something in particular), and if the offeree accepts this offer, a contract is created. As you can also see, both offer and acceptance must meet certain conditions.

A contract is legally enforceable: if one party fails to do what he or she has promised to do, the other can ask the courts to enforce the agreement or award damages for injury sustained because the contract has been breached—because a promise made under the contract hasn’t been kept or an act hasn’t been performed. A contract, however, can be enforced only if it meets four requirements (Cheesman, 2006):

- Agreement. The parties must have reached a mutual agreement. The offeror must have made an offer, and the offeree must have replied with an acceptance.

- Consideration. Each promise must be made in return for the performance of a legally sufficient act or promise. If one party isn’t required to exchange something of legal value (e.g., money, property, a service), an agreement lacks sufficient consideration.

- Contractual capacity. Both parties must possess the full legal capacity to assume contractual duties. Limitations to full capacity include mental illness and such diminished states as intoxication (Roszkowski, 2002).

- Lawful object. The purpose of the contract must be legal. A contract to commit an unlawful act or to violate public policy is void (without legal force).

Employment Contracts

Here’s where you come in: an employment relationship like the one that you had with your roommate is a contract. Under this contract, both parties have certain duties (you’re obligated to compensate your roommate, for instance, and he’s obligated to perform his assigned tasks in good faith). The law assumes that, when performing his employment duties, your employee is under your control—that you control the time, place, and method of the work (Moran, 2008). This is a key concept in your case.

Respondeat Superior

U.S. law governing employer-employee contracts derives, in part, from English common law of the seventeenth century, which established the doctrine known as respondeat superior—“Let the master answer [for the servant’s actions].” This principle held that when a servant was performing a task for a master, the master was liable for any damage that the servant might do (a practical consideration, given that servants were rarely in any position to make financial restitution for even minor damages) (Kubasek et. al., 2009; Law Library, 2008). Much the same principle exists in contemporary U.S. employment law, which extends it to include the “servant’s” violations of tort law. Your client—the homeowner—has thus filed a respondeat superior claim of negligence against you as your roommate’s employer.

Scope of Employment

In judging your responsibility for the damages done to the homeowner’s car by your employee, the court will apply a standard known as scope of employment: an employee’s actions fall within the scope of his employment under two conditions: (1) if they are performed in order to fulfill contractual duties owed to his employer and (2) if the employer is (or could be) in some control, directly or indirectly, over the employee’s actions (Law Library, 2008).

If you don’t find much support in these principles for the idea that your roommate was negligent but you weren’t, that’s because there isn’t much. Your roommate was in fact your employee; he was clearly performing contractual duties when he caused the accident, and as his employer, you were, directly or indirectly, in control of his activities. You may argue that the contract with your roommate isn’t binding because it was never put in writing, but that’s irrelevant because employment contracts don’t have to be in writing (Moran, 2008). You could remind the court that you repeatedly told your employee to put his paint bucket in a safer place, but this argument won’t carry much weight: in general, courts consider an employee’s forbidden acts to be within the scope of his employment (Law Library, 2008).

On the other hand, the same principle protects you from liability in the assault-and-battery case against your roommate. The court will probably find that his aggressive response to the neighbor’s comment wasn’t related to the business at hand or committed within the scope of his employment; in responding to the neighbor’s insult to his intelligence, he was acting independently of his employment contract with you.

Finally, now that we’ve taken a fairly detailed look at some of the ways in which the law works to make business relationships as predictable as possible, let’s sum up this section by reminding ourselves that the U.S. legal system is also flexible. In its efforts to resolve your case, let’s say that the court assesses the issues as follows:

The damage to the homeowner’s car amounts to $3,000. He can’t recover anything from your roommate, who owns virtually nothing but his personal library of books on medieval theology. Nor can he recover anything from your business-liability insurer because you never thought your business would need any insurance (and couldn’t afford it anyway). So that leaves you: can the homeowner recover damages from you personally? Legally, yes: although you didn’t go through the simple formalities of creating a sole proprietorship (see Chapter 5.2 for a refresher on sole proprietorships), you are nevertheless liable for the contracts and torts of your business. On the other hand, you’re not worth much more than your roommate, at least when it comes to financial assets. You have a six-year-old stereo system, a seven-year-old panel truck, and about $200 in a savings account—what’s left after you purchased the two ladders and the platform that you used as scaffolding. The court could order you to pay the $3,000 out of future earnings but it doesn’t have to. After all, the homeowner knew that you had no business-liability insurance but hired you anyway because he was trying to save money on the cost of painting his house. Moreover, he doesn’t have to pay the $3,000 out of his own pocket because his personal-property insurance will cover the damage to his car.

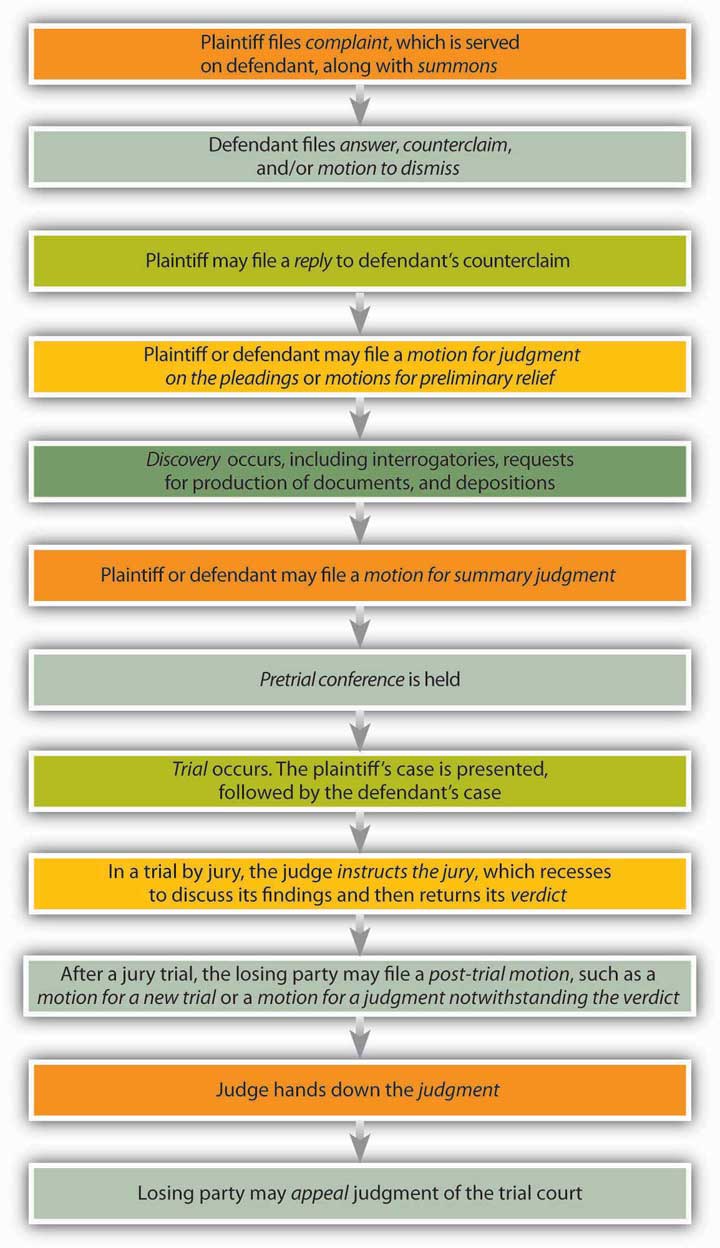

You should probably consider yourself lucky. Had your case gone to court, it would have been subject to the rules of civil procedure outlined in Figure 20.2: Stages in a Civil Lawsuit. As you might suspect, civil suits are time-consuming. Research shows that litigation takes an average of 24.2 months from the time a complaint is filed until a judgment is rendered (25.6 months if you’re involved in a tort lawsuit).

And of course it’s expensive. Let’s say that you have a $40,000-a-year job and decide to file a civil suit. Your lawyer will charge you between $200 and $350 an hour. At that rate, he or she will consume your monthly net income of about $1,800 in nine hours’ worth of work. But what about your jury award? Won’t that more than compensate you for your legal fees? It depends, but bear in mind that, according to one study, the median award in civil cases is $33,000 (Judicial Council of California, 2008) (Cohen & Smith, 2004). And you could lose.

Key Takeaways

-

A negligence tort results from carelessness. In order to prove a negligence claim, a plaintiff must demonstrate four elements:

- That the defendant owed a duty of care to the plaintiff. Duty of care refers to the basic obligation not to cause harm or an unreasonable risk of harm.

- That the defendant breached his duty of care. Did the defendant fail to act as a reasonable person would act?

- That the defendant’s breach of duty of care caused injury to the plaintiff or the plaintiff’s property.

- That the defendant’s action did in fact cause the injury in question. The direct cause-and-effect relationship between the defendant’s action and the plaintiff’s injury is called a cause in fact or actual cause. The point beyond which a defendant is no longer liable for the actions set in motion by his or her carelessness is called a proximate cause or legal cause. The standard for determining proximate cause is generally foreseeability: could the defendant reasonably foresee the possibility of the injury suffered by the plaintiff?

- A contract is an exchange of promises or an exchange of a promise for an act. An offeror makes an offer to enter into a contract with an offeree—that is, to do something in particular (or to refrain from doing something in particular). If the offeree accepts this offer, a contract is created.

-

A contract is legally enforceable: if one party fails to do what he or she has promised to do, the other can ask the courts to enforce the agreement or award damages for injury sustained because the contract has been breached. An enforceable contract must meet four requirements:

- Agreement. The parties must have reached a mutual agreement.

- Consideration. Each promise must be made in return for the performance of a legally sufficient act or promise.

- Contractual capacity. Both parties must possess the full legal capacity to assume contractual duties.

- Lawful object. The purpose of the contract must be legal.

- The law assumes that, in an employer–employee contract, the employer controls the time, place, and method of the employee’s work. The doctrine of respondeat superior—“Let the master answer [for the servant’s actions]”—applies to employer–employee contracts. In judging an employer’s responsibility for the damages caused by an employee’s negligence, the court will apply the standard of scope of employment: an employee’s actions fall within the scope of his employment under two conditions: (1) if they are performed in order to fulfill contractual duties owed to his employer and (2) if the employer is (or could be) in some control, directly or indirectly, over the employee’s actions.

Exercise

Let’s say you own a used car business and offer to sell a customer a used car for $5,000. What is needed to create a binding contract for the sale of the car?

If, when the customer wants to go for a test drive, the salesperson drives into a tree and is injured, is your company liable? Why, or why not?

References

Cheesman, H. R., Contemporary Business and Online Commerce Law: Legal, Internet, Ethical, and Global Environments, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2006), 79–83.

Cohen, T. H., and Steven K. Smith, “Civil Trial Cases and Verdicts in Large Counties, 2001,” Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin (Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Justice, April 2004), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ctcvlc01.pdf (accessed November 12, 2011).

Judicial Council of California, “Unlimited Civil Cases,” California Courts (2008), http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/reference/documents/retrounlimited.pdf

Kubasek, N. A., Bartley A. Brennan, and M. Neil Browne, The Legal Environment of Business: A Critical Thinking Approach, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2009), 446.

Law Library, “Respondeat Superior,” Law Library: American Law and Legal Information (2008), http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/respondeat+superior (accessed November 12, 2011).

Law Library, “Scope of Employment,” Law Library: American Law and Legal Information (2008), http://law.jrank.org/pages/10039/Scope-Employment.html (accessed November 12, 2011).

Moran, J. J., Employment Law: New Challenges in the Business Environment (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2008), 3.

Roszkowski, M. E., Business Law: Principles, Cases, and Policy, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002), 181.

refers simply to the basic obligation that one person owes another—the duty not to cause harm or an unreasonable risk of harm

an exchange of promises or an exchange of a promise for an act, and because it involves an exchange, it obviously involves at least two parties

if one party fails to do what he or she has promised to do, the other can ask the courts to enforce the agreement or award damages for injury sustained because the contract has been breached

a promise made under the contract hasn’t been kept or an act hasn’t been performed

an employee’s actions fall within the scope of his employment under two conditions: (1) if they are performed in order to fulfill contractual duties owed to his employer and (2) if the employer is (or could be) in some control, directly or indirectly, over the employee’s actions