3.3 The Individual Approach to Ethics

[Author removed at request of original publisher], Published by University of Minnesota

Betty Vinson didn’t start out at WorldCom with the intention of going to jail. She undoubtedly knew what the right behavior was, but the bottom line is that she didn’t do it. How can you make sure that you do the right thing in the business world? How should you respond to the kinds of challenges that you’ll be facing? Because your actions in the business world will be strongly influenced by your moral character, let’s begin by assessing your current moral condition. Which of the following best applies to you (select one)?

- I’m always ethical.

- I’m mostly ethical.

- I’m somewhat ethical.

- I’m seldom ethical.

- I’m never ethical.

Now that you’ve placed yourself in one of these categories, here are some general observations. Few people put themselves below the second category. Most of us are ethical most of the time, and most people assign themselves to category number two—“I’m mostly ethical.” Why don’t more people claim that they’re always ethical? Apparently, most people realize that being ethical all the time takes a great deal of moral energy. If you placed yourself in category number two, ask yourself this question: How can I change my behavior so that I can move up a notch? The answer to this question may be simple. Just ask yourself an easier question: How would I like to be treated in a given situation (Maxwell, 2003)?

Unfortunately, practicing this philosophy might be easier in your personal life than in the business world. Ethical challenges arise in business because business organizations, especially large ones, have multiple stakeholders and because stakeholders make conflicting demands. Making decisions that affect multiple stakeholders isn’t easy even for seasoned managers; and for new entrants to the business world, the task can be extremely daunting. Many managers need years of experience in an organization before they feel comfortable making decisions that affect various stakeholders. You can, however, get a head start in learning how to make ethical decisions by looking at two types of challenges that you’ll encounter in the business world: ethical dilemmas and ethical decisions.

Addressing Ethical Dilemmas

An ethical dilemma is a morally problematic situation: You have to pick between two or more acceptable but often opposing alternatives that are important to different groups. Experts often frame this type of situation as a “right-versus-right” decision. It’s the sort of decision that Johnson & Johnson (known as J&J) CEO James Burke had to make in 1982 (Kaplan, 2012). On September 30, twelve-year-old Mary Kellerman of Chicago died after her parents gave her Extra-Strength Tylenol. That same morning, twenty-seven-year-old Adam Janus, also of Chicago, died after taking Tylenol for minor chest pain. That night, when family members came to console his parents, Adam’s brother and his wife took Tylenol from the same bottle and died within forty-eight hours. Over the next two weeks, four more people in Chicago died after taking Tylenol. The actual connection between Tylenol and the series of deaths wasn’t made until an off-duty fireman realized from news reports that every victim had taken Tylenol. As consumers panicked, J&J pulled Tylenol off Chicago-area retail shelves. Researchers discovered Tylenol capsules containing large amounts of deadly cyanide. Because the poisoned bottles came from batches originating at different J&J plants, investigators determined that the tampering had occurred after the product had been shipped.

So J&J wasn’t at fault. But CEO Burke was still faced with an extremely serious dilemma: Was it possible to respond to the tampering cases without destroying the reputation of a highly profitable brand? Burke had two options:

- He could recall only the lots of Extra-Strength Tylenol that were found to be tainted with cyanide. This was the path followed by Perrier executives in 1991 when they discovered that cases of bottled water had been poisoned with benzine. This option favored J&J financially but possibly put more people at risk.

- Burke could order a nationwide recall—of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol. This option would reverse the priority of the stakeholders, putting the safety of the public above stakeholders’ financial interests.

Burke opted to recall all 31 million bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol on the market. The cost to J&J was $100 million, but public reaction was quite positive. Less than six weeks after the crisis began, Tylenol capsules were reintroduced in new tamper-resistant bottles, and by responding quickly and appropriately, J&J was eventually able to restore the Tylenol brand to its previous market position. When Burke was applauded for moral courage, he replied that he’d simply adhered to the long-standing J&J credo that put the interests of customers above those of other stakeholders. His only regret was that the tamperer was never caught (Weber, 1999).

If you’re wondering what your thought process should be if you’re confronted with an ethical dilemma, you could do worse than remember the steps listed here as James Burke addressed the Tylenol crisis:

- Define the problem: How to respond to the tampering case without destroying the reputation of the Tylenol brand.

- Identify feasible options: (1) Recall only the lots of Tylenol that were found to be tainted with cyanide or (2) order a nationwide recall of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol.

- Assess the effect of each option on stakeholders: Option 1 (recalling only the tainted lots of Tylenol) is cheaper but puts more people at risk. Option 2 (recalling all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol) puts the safety of the public above stakeholders’ financial interests.

- Establish criteria for determining the most appropriate action: Adhere to the J&J credo, which puts the interests of customers above those of other stakeholders.

- Select the best option based on the established criteria: In 1982, Option 2 was selected, and a nationwide recall of all bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol was conducted.

Making Ethical Decisions

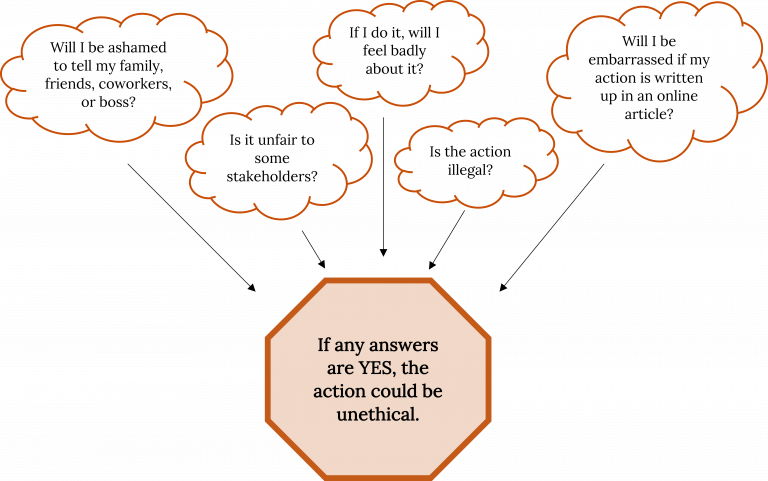

In contrast to the “right-versus-right” problem posed by an ethical dilemma, an ethical decision entails a “right-versus-wrong” decision—one in which there is a right (ethical) choice and a wrong (unethical or illegal) choice. When you make a decision that’s unmistakably unethical or illegal, you’ve committed an ethical lapse. Betty Vinson, for example, had an ethical lapse when she caved in to her bosses’ pressure to cook the WorldCom books. If you’re presented with what appears to be this type of choice, asking yourself the questions in Figure 3.4: How to Avoid an Ethical Lapse will increase your odds of making an ethical decision.

To test the validity of this approach, let’s take a point-by-point look at Betty Vinson’s decisions:

- Her actions were clearly illegal.

- They were unfair to the workers who lost their jobs and to the investors who suffered financial losses (and also to her family, who shared her public embarrassment).

- She definitely felt bad about what she’d done.

- She was embarrassed to tell other people what she had done.

- Reports of her actions appeared in her local newspaper (and just about every other newspaper in the country).

So Vinson could have answered our five test questions with five yeses. To simplify matters, remember the following rule of thumb: If you answer yes to any one of these five questions, odds are that you’re about to do something you shouldn’t.

Revisiting Johnson & Johnson

As discussed earlier in this section, Johnson & Johnson received tremendous praise for the actions taken by its CEO, James Burke, in response to the 1982 Tylenol catastrophe. But things change. To learn how a company can destroy its good reputation, let’s fast forward to 2008 and revisit J&J and its credo, which states, “We believe our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses and patients, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services. In meeting their needs everything we do must be of high quality” (Credo, Johnson & Johnson, 2011). How could a company whose employees believed so strongly in its credo find itself under criminal and congressional investigation for a series of recalls due to defective products? (Kimes, 2010) In a three-year period, the company recalled twenty-four products, including Children’s, Infants’ and Adults’ Tylenol, Motrin, and Benadryl (McNeil Product Recall Informations, 2011); 1-Day Acuvue TruEye contact lenses sold outside the U.S. (Berkrot, 2010); and hip replacements (New York Times, 2010).

Unlike the 1982 J&J Tylenol recall, no one died from the defective products, but customers were certainly upset to find they had purchased over-the-counter medicines for themselves and their children that were potentially contaminated with dark particles or tiny specks of metal (Kimes, 2010); contact lenses that contained a type of acid that caused stinging or pain when inserted in the eye (Rockoff & Kamp, 2010); and defective hip implants that required patients to undergo a second hip replacement (Singer, 2010).

Who bears the responsibility for these image-damaging blunders? We’ll identify two individuals who were at least partially responsible for the decline of J&J’s reputation: The first is the current CEO—William Weldon—who has been criticized for being largely invisible and publicly absent during the recalls (Kimes, 2010). Additionally, he admitted that he did not understand the consumer division where many of the quality control problems originated (Kimes, 2010). Some members of the board of directors were not pleased with his actions (or inactions) and were upset at the revenue declines from the high-profile recalls. Consequently, Weldon was given only a 3 percent raise for 2011, and his end-of-year bonus was cut by 45 percent. But don’t cry for him: His annual compensation for the year (including salary, bonus, and stock options) was $23 million—down from $26 million in the previous year (Perrone, 2011).

After learning that J&J had released packets of Motrin that did not dissolve correctly, the company hired contractors to go into convenience stores and secretly buy up every pack of Motrin on the shelves. The instructions given to the contractors were the following: “You should simply ‘act’ like a regular customer while making these purchases. THERE MUST BE NO MENTION OF THIS BEING A RECALL OF THE PRODUCT!”[25] In May 2010, when Goggins appeared before a congressional committee investigating the “phantom recall,” she testified that she was not aware of the behavior of the contractors[26] and that she had “no knowledge of instructions to contractors involved in the phantom recall to not tell store employees what they were doing.” In her September 2010 testimony to the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, she acknowledged that the company in fact wrote those very instructions. In 2020, Johnson & Johnson is discontinuing their baby powder, one of their flagship products, because of the cancer-related issues found from the talc, an ingredient in the powder. This time, they are being proactive.[27]

Refusing to Rationalize

Despite all the good arguments in favor of doing the right thing, why do many reasonable people act unethically (at least at times)? Why do good people make bad choices? According to one study, there are four common rationalizations (excuses) for justifying misconduct:

- My behavior isn’t really illegal or immoral. Rationalizers try to convince themselves that an action is OK if it isn’t downright illegal or blatantly immoral. They tend to operate in a gray area where there’s no clear evidence that the action is wrong.

- My action is in everyone’s best interests. Some rationalizers tell themselves: “I know I lied to make the deal, but it’ll bring in a lot of business and pay a lot of bills.” They convince themselves that they’re expected to act in a certain way.

- No one will find out what I’ve done. Here, the self-questioning comes down to “If I didn’t get caught, did I really do it?” The answer is yes. There’s a simple way to avoid succumbing to this rationalization: Always act as if you’re being watched.

- The company will condone my action and protect me. This justification rests on a fallacy. Betty Vinson may honestly have believed that her actions were for the good of the company and that her boss would, therefore, accept full responsibility (as he promised). When she goes to jail, however, she’ll go on her own.

Here’s another rule of thumb: If you find yourself having to rationalize a decision, it’s probably a bad one.

Easy to Remember Ethical Tests to Help With Decision Making—What to do When the Light Turns Yellow

Ethical decision making can be difficult when balancing multiple stakeholder interests. It is compounded when there is added pressure and a lack of time for good analysis and review. There are a couple simple Ethical Strategies that can help with personal decision making or at least remind you to pump the brakes if needed.

- The Golden Rule – Treat others the way you expect to be treated.[30]

- The Grandma Rule – This is also called the Loved-one Rule. When balancing options, think about what an elder you respect may think of the options if you had to review it with them later.[31]

- The Sunshine Rule – This concept has been articulated in a number of ways. Think about how your plan may look in the light of day or on the front page of the newspaper. In this context it may be easier to consider if certain action is justified.[32]

- The Rule of the Big 4. When faced with a challenging situation or an option if you ask yourself these 4 questions it may help reveal if there is a linked ethical problem.[33]

- Is the decision HAZY? Are there elements to the issue that appear to be hidden or unclear? Do those items need to be revealed?

- Is the decision LAZY? Is the path forward or decision made with any effort? Is more work expected of you to make a good decision?

- Is the decision based on GREED? Who stands to gain by the decision? Is the decision being made for the good of the company and the stakeholders involved or is it based on personal greed?

- Is the decision made out of SPEED? Was there a rush to judgment without all of the facts?

What to Do When the Light Turns Yellow

Like our five questions, some ethical problems are fairly straightforward. Others, unfortunately, are more complicated, but it will help to think of our five-question test as a set of signals that will warn you that you’re facing a particularly tough decision—that you should think carefully about it and perhaps consult someone else. The situation is like approaching a traffic light. Red and green lights are easy; you know what they mean and exactly what to do. Yellow lights are trickier. Before you decide which pedal to hit, try posing our five questions. If you get a single yes, you’ll be much better off hitting the brake (Online Ethics Center for Engineering and Science, 2006).

Key Takeaways

- Businesspeople face two types of ethical challenges: ethical dilemmas and ethical decisions.

- An ethical dilemma is a morally problematic situation in which you must choose between two or more alternatives that aren’t equally acceptable to different groups.

-

Such a dilemma is often characterized as a “right-versus-right” decision and is usually solved in a series of five steps:

- Define the problem and collect the relevant facts.

- Identify feasible options.

- Assess the effect of each option on stakeholders (owners, employees, customers, communities).

- Establish criteria for determining the most appropriate option.

- Select the best option, based on the established criteria.

- An ethical decision entails a “right-versus-wrong” decision—one in which there’s a right (ethical) choice and a wrong (unethical or downright illegal) choice.

- When you make a decision that’s unmistakably unethical or illegal, you’ve committed an ethical lapse.

-

If you’re presented with what appears to be an ethical decision, asking yourself the following questions will improve your odds of making an ethical choice:

- Is the action illegal?

- Is it unfair to some parties?

- If I take it, will I feel bad about it?

- Will I be ashamed to tell my family, friends, coworkers, or boss about my action?

- Would I want my decision written up in the local newspaper?

If you answer yes to any one of these five questions, you’re probably about to do something that you shouldn’t.

Exercise

Explain the difference between an ethical dilemma and an ethical decision. Then provide an example of each. Describe an ethical lapse and provide an example.

1“J&J’s Colleen Goggins Sells Nearly $3M in Stock,” Citibizlist, September 14, 2010 (accessed August 16, 2011).

References

Berkrot, B., “J&J Confirms Widely Expanded Contact Lens Recall,” December 1, 2010, http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/12/01/us-jandj-recall-idUSTRE6B05G620101201 (accessed August 12, 2011).

Credo, Johnson & Johnson company Web site, http://www.jnj.com/connect/about-jnj/jnj-credo (accessed August 15, 2011).

Kaplan, T., “The Tylenol Crisis: How Effective Public Relations Saved Johnson & Johnson,” http://www.aerobiologicalengineering.com/wxk116/TylenolMurders/crisis.html (accessed January 22, 2012).

Kimes, M., “Why J&J’s Headache Won’t Go Away,” Fortune (CNNMoney), August 19, 2010, http://money.cnn.com/2010/08/18/news/companies/jnj_drug_recalls.fortune/index.htm (accessed August 12, 2011).

Maxwell, J. C., There’s No Such Thing as “Business Ethics”: There’s Only One Rule for Making Decisions (New York: Warner Books, 2003), 19–21.

McNeil Product Recall Information, http://www.mcneilproductrecall.com/ (accessed August 12, 2011).

New York Times, Business Day, August 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/business/27hip.html (accessed August 12, 2011).

Online Ethics Center for Engineering and Science, “Advice from the Texas Instruments Ethics Office: What Do You Do When the Light Turns Yellow?” Onlineethics.org, http://onlineethics.org/corp/help.html#yellow (accessed April 24, 2006).

Perrone, M., “J&J CEO Gets 3% Raise, but Bonus Is Cut,” USA Today, February 25, 2011, http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/health/2011-02-25-jnj_N.htm (accessed August 15, 2011).

Rockoff J. D., and Jon Kamp, “J&J Contact Lenses Recalled,” Wall Street Journal, Health section, August 24, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703846604575447430303567108.html (accessed August 15, 2011).

Silverman, E., “Recall Fallout? Johnson & Johnson’s Goggins to Retire,” Pharmalot, September 16, 2010, http://www.pharmalot.com/2010/09/recall-fallout-johnson-johnsons-goggins-to-retire/ (accessed August 15, 2010).

Singer, N., “Johnson & Johnson Recalls Hip Implants,” New York Times, Business Day, August 20, 2010, http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/27/business/27hip.html (accessed August 12, 2011).

Weber, Y., “CEO Saves Company’s Reputation, Products,” New Sunday Times, June 13, 1999, http://adtimes.nstp.com.my/jobstory/jun13.htm (accessed April 24, 2006).

is a morally problematic situation: You have to pick between two or more acceptable but often opposing alternatives that are important to different groups

right-versus-wrong” decision—one in which there is a right (ethical) choice and a wrong (unethical or illegal) choice

When you make a decision that’s unmistakably unethical or illegal